Kevin Rudd and me: the PM, the editor and beers with the Daily Telegraph boys

Kevin Rudd’s desperation to ingratiate himself with Rupert Murdoch and our company was so extreme we almost needed a restraining order.

It was like a scene out of a western when we arrived at the front doors of the Gaslight Inn, a trendy pub in the inner-Sydney suburb of Darlinghurst.

The bar was packed and loud but the place fell silent as everyone realised who was standing there. Slowly, the chanting started.

“Ke-vin! Ke-VIN! KE-VIN!”

As the two of us walked in, it rose to a deafening roar.

“KE-VIN! KE-VIN! KE-VIN!”

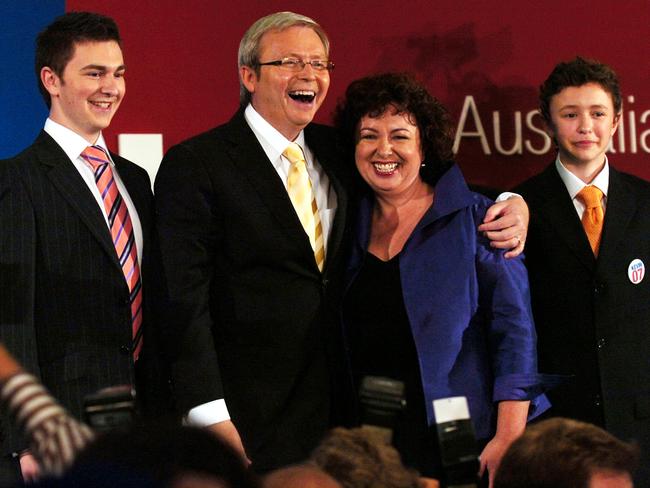

Kevin Rudd couldn’t wipe the smile off his face. It was about 11pm on a Friday in mid-2007, and the opposition leader was riding an unstoppable wave of national popularity that its most adept chronicler, the late Matt Price, dubbed The Age of Kevinism.

I bought the first round of beers as fans queued for handshakes, hugs and selfies with Rudd. Two blokes invited us to play doubles in eight ball. Rudd broke, sending the white ball flying off the table.

That Friday night in Surry Hills was one of a dozen or so meals I had with Rudd on his ascent to the Labor leadership and subsequent election as prime minister. Between those meals I spoke with him by phone and, more often, by text, on countless occasions. Rudd sought me out in my capacity as editor of Sydney’s Daily Telegraph, a role I held from April 2005 to November 2008, giving me a front-row seat for the end of the Howard era and the Rudd victory.

We would have dinner together at a now-defunct French bistro called Tabou on Crown Street near the News Corp offices in Surry Hills, and sometimes head out for a cleanser after.

When he became PM, Rudd organised several nights at Kirribilli House for what he liked to call “The Tele Boys”, which meant myself, Luke McIlveen, Joe Hildebrand, Simon Benson, and when he was up in Sydney from Canberra, our national political editor Malcolm Farr. A couple of these nights finished around 3am, and they always involved a strange tradition invented by Rudd where he would challenge us to a running race up the hill at the harbourside property.

INSIDE STORY: Captain Chaos and the workings or Rudd’s inner circle

None of this is meant to sound like big-noting. You could sit a shop mannequin in an editor’s chair and the most ingratiating politicians would still be lining up to kiss it on the backside. I just happened to be the mannequin.

That said, our newspaper played a pivotal role in covering the transition from John Howard to Rudd. And reflecting on our coverage, especially in 2007, the year of Howard’s defeat, you could ask whether the former member for Bennelong might be the one asking for a royal commission into the conduct of News Corp, publisher of The Australian, given the thoroughness with which we documented his demise, convinced as we increasingly were of its inevitability.

And while Rudd now claims to be smited, the truth is that Rudd enjoyed one of the greatest armchair rides Australian politics has ever seen. I know. I was holding one of the armchairs.

I said that Rudd sought me out as editor. That is an understatement. Rudd was incessant in his desire to engage with and use the media to realise his desire for power. He was particularly desperate to win favour with The Daily Telegraph as the paper that had both coined the term and represented the Howard battlers, the vast swath of aspirational voters in suburban marginal seats across Sydney who make and break governments.

Mr Rudd’s media strategy occurred over three phases: his calculated white-anting of his predecessor as Labor leader, Kim Beazley; his seeing off of Howard; and his protracted campaign of vengeance against Julia Gillard as payback for the 2010 coup, when he would habitually refer to Australia’s first female prime minister as “that f..king bitch” in obscenity-filled backgrounding calls to journalists and editors tearing her down.

Moves on Beazley

One of my earliest contacts with Rudd came out of the blue and followed a fairly mundane Tele splash, headed BILL FOR PM, when in 2006 Farr wrote that key Labor figures were talking up Bill Shorten in light of his compassionate leadership at the Beaconsfield mine collapse and amid continuing concerns over Beazley’s electability.

Rudd rang me the next day asking if the paper was taking a formal pro-Shorten position; I laughed and said ‘no, mate, it’s your party, not ours, we just didn’t have anything else to splash with’. Whatever the case, Rudd reassured me he would be coming down from Brisbane soon and wanted to have dinner, as if we needed to discuss the matter urgently.

Later that year I was in Melbourne at the Crown Towers trying to do up my bow tie to go to some tedious event. The phone rang and it was Rudd.

“I presume you saw that,” he began, in reference to the excruciating press conference Beazley had held that day. Instead of paying condolences to comedian Rove McManus over the death of his wife Belinda Emmett from cancer, he extended his sympathies to US Republican strategist Karl Rove.

Rudd spent a good five minutes telling me that Beazley was clearly not well. The Labor leader had been diagnosed two years earlier with Chaltenbrand’s syndrome, a condition where cerebrospinal fluid leaks from around the brain, and Rudd put it to me that there was still something wrong with him and he was not facing up to that. Other journalists were receiving similar information from their sources.

Reporting the story in The Age the following day, Michelle Grattan wrote: “The mistake, capping a bad week for the Opposition Leader, has given ammunition to his party enemies and sparked fresh speculation about his health and the leadership. One Labor source said yesterday: ‘I think there is something wrong with him. He is not facing up to that’.”

Fifteen days later, Rudd was Labor leader.

The backgrounder

That Beazley phone call was a powerful example of Rudd’s manipulation of the “off the record” convention in journalism, where an evening of vigorous, speed-dial backgrounding could be followed the following day by feigned disbelief at all the darned rumours.

It reached a comical zenith during the campaign to roll Gillard, when Rudd loyalist Doug Cameron said the Murdoch press was “telling lies” by reporting that Rudd wanted his job back, when behind the scenes, Cameron, Rudd and their backers were doing everything short of homicide to make sure he got it.

By 2006 it was not even a remote surprise to me that Rudd had single-minded designs on seizing the Labor leadership. I knew this because I had been asked to help him do it. I had been sounded out about it explicitly by his key NSW Right numbers man, former ALP state secretary Mark Arbib. Sounded out is too delicate a term — at one of our semi-regular catch-ups at the Darlinghurst pasta joint Bill and Tony’s, Arbib asked point-blank if The Daily Telegraph would “support” Rudd if he ran against Beazley. I was amazed by the question, figuring it a matter for caucus first, and subsequently the people, not some bloke who happened to edit a newspaper. I said we would give him as fair a hearing as anyone if he got the job.

Weaknesses emerge

With hindsight, there were signs when Rudd became opposition leader of the mental fragility and explosive temperament that would see caucus turn against him in record time at the 2010 coup.

Of these, the biggest was his handling of the so-called Sunrise affair, where Rudd’s office was accused of conspiring with the Seven Network to shift the timing of an Anzac dawn service to better suit the breakfast show’s ratings.

My parents were over from Adelaide in Sydney that Sunday in April 2007 and I hadn’t yet read the day’s papers. We were having breakfast at an Italian place in Haberfield when the phone rang.

“Hi Kev, how are you?” I asked.

“How am I? Have you seen the f..king Sunday Telegraph? Not just the Sunday Telegraph but the f..king paper in Brisbane, the Sunday Herald Sun in Melbourne, even that f..king rag in your hometown? How am I? Thanks to your newspapers, about 10 million Australians think I’m a f..king c...!”

“Come on, I’m sure it’s not that many,” I replied, failing to elicit a laugh.

Weirdly, the reason Rudd had rung was to seek advice from me — which was not forthcoming — about how best he could prosecute the case against News Corp over this story. He wanted to know if I thought he should call the Sunday Telegraph’s editor, Neil Breen, or go to the top by calling our chief executive John Hartigan. Keen to return to some rare time with my parents, I told him it had nothing to do with me, especially as I didn’t edit any of those newspapers anyway, and he was free to call whoever the hell he liked.

In a huge overreach, Rudd ended up publicly demanding Breen’s sacking in a kind of high-noon scenario where he gave the paper three days to produce evidence of any knowledge of the dawn service plan. When that very evidence turned up, and the papers were vindicated, I took great delight in plastering the words RUDD’S FALSE DAWN over the front page the following day.

By late 2007, none of this mattered a jot. Blow-ups such as the dawn service scandal or the salacious silliness of the Scores affair, where he got chucked out of the New York strip club, were having no negative impact on Rudd at all.

The mood that Price had detected was resonating across Australia. My reading of our readers was that, in Sydney, no one in The Daily Telegraph audience hated Howard, they simply believed he had run his race. They thought he had been a great prime minister, but his time had come, as Howard himself had indicated with the clunky transition plan to Peter Costello.

There was also a largely uncontested mainstream belief in 2007 that action was needed on climate change. Beyond that, most Australians — including many newspaper editors — were labouring under the delusion that Rudd was not just a fiscal conservative but a well-adjusted bloke who would deliver stable government.

This reading of the mood at the time was backed up by opinion polls that were proven to be right on polling day, supported by party research from both sides to which I was privy, reflected in vox-pops our journalists did in seats such as Parramatta and Lindsay, and confirmed by the Liberal Party’s own Crosby Textor research which in a devastating leak landed square in our laps at The Daily Telegraph, showing that even the Libs knew they were gone.

Howard’s demise

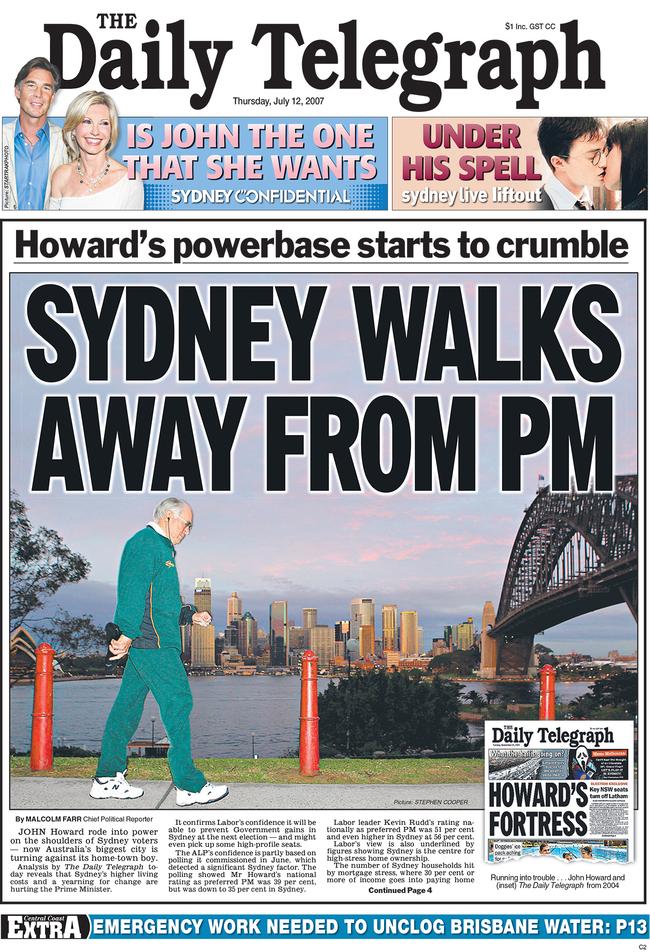

Our paper was the first to chronicle the fact that Howard was in strife in his hometown and we splashed with a story headed “SYDNEY WALKS AWAY FROM PM” on July 12, 2007, which said there was a 20-point approval differential in Rudd’s favour and that the Liberals could lose key Sydney seats.

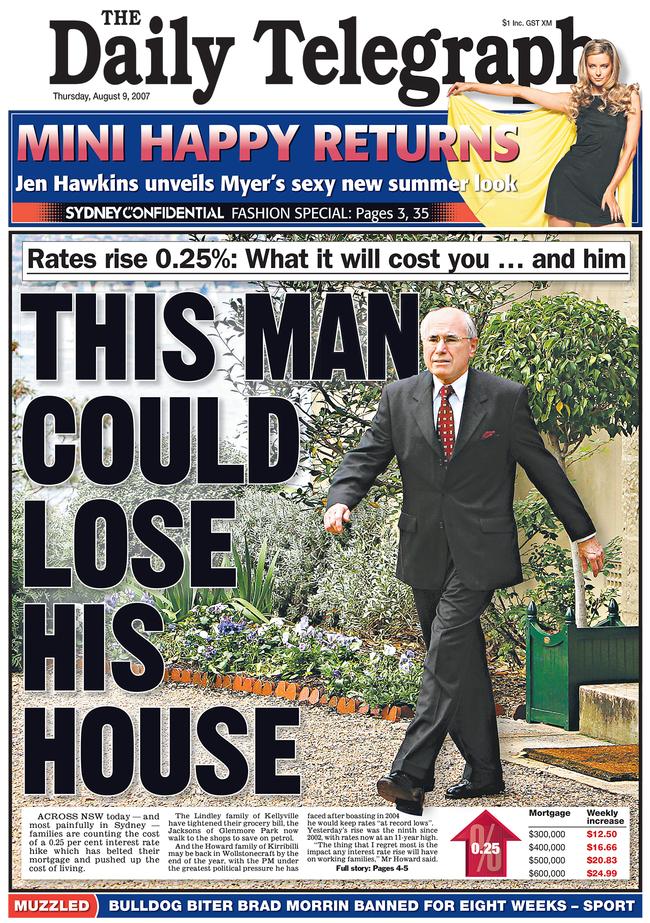

There were other strong front pages. When interest rates, long the trump in Howard’s deck, jumped on election eve, we ran a picture of the prime minister outside Kirribilli with the headline “THIS MAN COULD LOSE HIS HOUSE”.

On the Thursday before polling day, we hammered the final nail into Howard’s political coffin. A disgusted Liberal Party figure had tipped off the then NSW ALP assistant secretary Luke Foley that Liberal branch members loyal to Lindsay Liberal MP Jackie Kelly — including her husband Gary Clark — had been distributing fake pamphlets in Lindsay claiming Labor not only backed the construction of a mosque in the suburb of St Marys but also supported the Bali bombers.

In a sting operation, Foley led a group of ALP members into the night with cameras and caught the pamphleteers, with the story and photographs handed exclusively to The Tele. Our front page that Thursday — the same day that Howard had to address the National Press Club to wrap up the campaign — had the words “LIBS BUSTED” on page one in 180-point with the gotcha photo of Clark, his face obscured by a piece of blue paper bearing the misspelt words “Ala Akba”.

Lindsay defeat

The Howard era would end where it had begun, with the seat that epitomised the Howard battlers in 1996 falling to Labor amid amateurish scandal in 2007.

I saw Howard not long before the 2007 election at a rugby league function and we sat on the same table. I had got to know him well as The Advertiser’s Canberra correspondent between 1996 and 1999 when he was always generous with his time.

I had dined with him often at (more civilised) functions at Kirribilli House and The Lodge as a journalist and editor. Howard approached me that night after the meal and said quietly: “Now Mr Penberthy, am I right in detecting a certain editorial shift?”

I said he was. I said we weren’t trying to dance on his political grave, but that our reading of the mood was that things were shifting. He smiled and said: “Well, I hope you note that you haven’t been getting any profanity-laden phone calls from me.”

There was an editor’s dinner late in 2007 at Rockpool attended by Rupert Murdoch and every major News Corp editor in Australia. He asked us to go around the room and explain what our election editorials were going to say and why. Some backed Rudd, some stuck with Howard, everyone gave their reasons and no one was issued with any instructions.

Rudd won. And we backed him in our editorial, as did The Australian, although on reflection our leader read less like an impassioned argument for Rudd than a rueful farewell to Howard.

Farewell conversation

After the election I wrote a personal letter to Howard congratulating him on his distinguished career, thanking him for the access he had kindly given me and our papers, and apologising for bidding him farewell in our election editorial.

“Thank you for your letter,” Howard replied soon after. “I appreciated your kind personal remarks. Needless to say, I was disappointed that your newspaper went over to the dark side after such a long and positive association. That, as they say, is the nature of things in a democracy. It was a huge privilege to have been at the helm for so long and I, too, enjoyed the association with the Telegraph.”

This picture of graciousness and even-handedness is a stark contrast to the conduct we are seeing from Rudd towards our company now. Unlike Howard — and unlike so many other Liberal and Labor leaders who have been the subject of editorials and coverage both good and bad — the Rudd campaign seems to be rooted more in his own psychology.

If you wanted a headline to describe the relationship between Murdoch and Rudd it would be this: Media figure stalked by crazed fan. His enthusiasm to ingratiate himself with our company was so extreme that we almost needed to obtain a restraining order. Rudd now believes the company is evil and that it misuses its power and picks winners.

My dealings with Rudd and his backers show that he was the one desperate to use that power, even to have it misused by seeking some kind of formal media endorsement as leader. And when it comes to picking winners, from all I saw of Rudd’s conduct with myself, other editors and our proprietor, he was the one who like a schoolboy before a football match imploring: “Pick me, pick me.”

This push for a royal commission is driven less by facts and more by the shared mental state of Rudd, and his new sidekick Malcolm Turnbull. It is, for them, a coping mechanism. It is psychologically more palatable for them to ascribe their demise not to their own imperiousness, policy failure or inability to consult and listen, but a sinister external conspiracy.

On the day my stint as editor ended in late 2008, there were drinks at the work pub to farewell me and honour my successor, Garry Linnell. I didn’t stick around long because I regarded the occasion as Linnell’s night, and had made a strange pact with myself four years prior that on the day of my departure I would go home and lie on the lawn.

I was lying on the lawn when the phone rang.

“Penbo, I just want you to know that I’m ringing you as a mate to make sure you’re all right,” Rudd said. “Now, what can you tell me about the new guy?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout