OPEC deal ‘too late’ to prevent oil glut

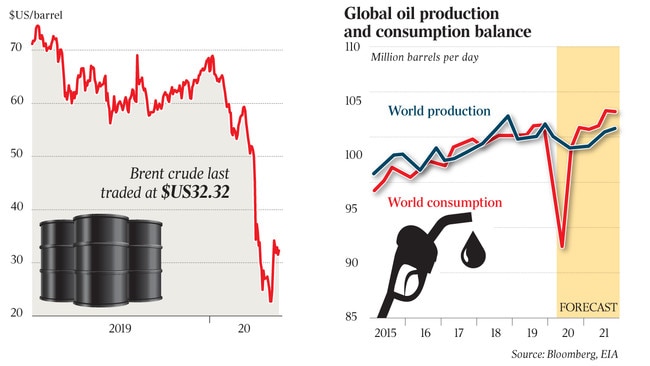

The deal between OPEC and its allies won’t stop a massive oil glut potentially sending crude prices back to $US20 a barrel.

It was the kind of deal you reach when you have to make a deal and in many ways it wasn’t perfect, but the historic agreement between OPEC and its allies to cut oil supply by almost 10 per cent should help put a floor under prices, notwithstanding short-term oversupply.

Brokered by US President Donald Trump after days of tense negotiations and sweetened by supply commitments from G20 energy producers, the agreement by the major oil producers was the latest sign that world leaders will do whatever it takes to prevent another global financial crisis. But while ending a damaging price war amid a severe economic slump, analysts say it won’t stop a massive oil glut potentially sending crude prices back to $US20 a barrel in the short term.

Brent crude oil futures initially surged 8 per cent at $US33.99 a barrel when trading resumed in Asia, before paring its rise to 1 per cent. The US sharemarket reacted cautiously with S&P 500 futures down more than 1 per cent after a 25 per cent bounce in the US benchmark in the past three weeks.

Even with a commitment by other producers to cut as much as 5 million barrels a day, the OPEC+ agreement to cut exports by a record 9.7 million barrels a day in May and June, tapering to 8 million in mid-2020 and 6 million in January 2021 — assuming full compliance — won’t offset an expected 19 million-barrel-a-day loss of demand in April and May due to the coronavirus.

“However large and credible the combined OPEC+ and G-20 cuts, the main problem is timing,” said Citi’s global head of commodities research, Edward Morse. “It’s simply too late to prevent a super-large inventory build of over 1 billion barrels between mid-March and late May and to stop spot prices from falling into single digits.”

With the slated production cuts only starting to reduce delivery of crude from June, he expected oil prices to fall again, triggering further “involuntary” production cuts which rebalance the market.

But while combined cuts by OPEC+ and projected reductions by other G-20 producers will play only a small role in limiting inventory builds in the June quarter, Mr Morse saw a significant impact on inventories and raising prices to the mid-$US40s or higher by year-end.

By the September quarter, he expected the production cuts to “make a difference” that lowers crude oil inventory for the rest of 2020.

“That’s why these cuts are meaningful and why Citi has revised its September quarter and December quarter price (forecasts) up to $US35 and $US45 for Brent, and (for) 2021 up to $US56.”

While acknowledging “ambiguity and fudging” and “confusion over what baseline applies to which country”, Mr Morse added that OPEC+ had “convincingly committed” to reduce exports by 9.7 million barrels a day in May and June, and its de facto leaders — its largest producers Saudi Arabia and Russia — effectively reducing exports by 4 and 2.5 million barrels a day respectively.

“What’s more, many of the countries involved are actually likely to produce less than their commitments in the June quarter, invoking force majeure factors in not being able to fulfil export commitments, whether due to price levels or lack of refinery buying.”

And in a measure of just how seriously world leaders are taking the COVID-19 crisis, the US “played a critical role” in convincing Saudi Arabia and Russia to negotiate the new accord, and together with the International Energy Agency, convinced Saudi Arabia to convene a special G-20 meeting for a co-ordinated response. Despite concerns that the commitments of the other producers to cut by as much as 5 million barrels a day aren’t “real” since that’s an estimate of lost production rather than a policy response, Mr Morse said they were more likely to occur and less subject to quick reversal than the OPEC+ cuts.

“The latter are more likely to be reversed by Saudi or Russian decisions than the cuts from the three largest unconventional producers: the US, Canada and Brazil,” he said.

Echoing the concern about oversupply in the short-term, Goldman Sachs’ head of commodities research, Jeffrey Currie, said that even “optimistically” assuming full compliance from core-OPEC and 50 per cent compliance by all other participants — the OPEC+ “voluntary cut” would only lead to an actual 4.3 million barrels a day reduction in production from March quarter levels.

“Given the difficulty for most producers outside of core-OPEC to implement large cuts, today’s agreement leaves the voluntary cuts as still too little and too late to avoid breaching storage capacity, ensuring that low oil prices force all producers to contribute to the market rebalancing,” Mr Currie said.

“Ultimately, this simply reflects that no voluntary cuts could be large enough to offset the 19 million barrels a day average April-May demand loss due to the coronavirus.”

Mr Currie expected US crude oil prices to fall in the coming weeks as “storage capacity becomes saturated” and he saw West Texas crude falling to $US20 a barrel in the short term.

The IEA is due to provide an update on Wednesday on plans by some countries that are net consumers of oil to increase their strategic oil reserves, but Mr Currie said he didn’t see US strategic Petroleum Reserve purchases changing the supply-demand balance.

On his estimates, combined commercial and government storage capacity will be reached by late April, with 4 million barrels a day of production shut-ins required even before the OPEC+ deal starts.

“Such a high SPR purchase pace would further likely be logistically difficult as strategic reserves are designed for fast drawdowns not fills, and typically operate at high utilisation levels with low spare capacity,” Mr Currie said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout