Investors see delight but swift bounce may be false dawn

Huge gains in global risk assets from multi-year lows last month may be hard to sustain.

Huge gains in global risk assets from multi-year lows last month show how positively investors have reacted to unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus, combined with signs that extreme measures to fight the coronavirus pandemic are working. Such a strong recovery may be hard to sustain.

The outcome of a G20 energy ministers’ meeting, expected to confirm a production cut of at least 10 million barrels a day — as well as coronavirus statistics and official guidance on how soon life might start to normalise from the severe lockdowns, and whether any further stimulus is coming — will determine whether this “risk rally” keeps going in the short term.

But it’s fair to say that a lot of good news has already been priced in. Indeed, what would normally be spectacular gains for a year have occurred in the space of weeks. On a daily close-to-close basis, the S&P 500 rose 22.9 per cent in just over 12 days, its fastest move off a bear market low since the end of the last bear market in March 2009.

It was also the second-shortest US bear market in history — just 19 days — but that’s not necessarily positive. After the shortest bear market ended in November 1929, the S&P 500 went on to bounce 47 per cent off the initial low of the 1929 crash, before plunging 83 per cent over the next 27 months.

The S&P 500 extended its run-up on Thursday night, adding 1.5 per cent to 2789.8 points despite a higher-than-expected 6.6 million new jobless claims.

Of course, monetary and fiscal policy settings now are vastly different to the Great Depression.

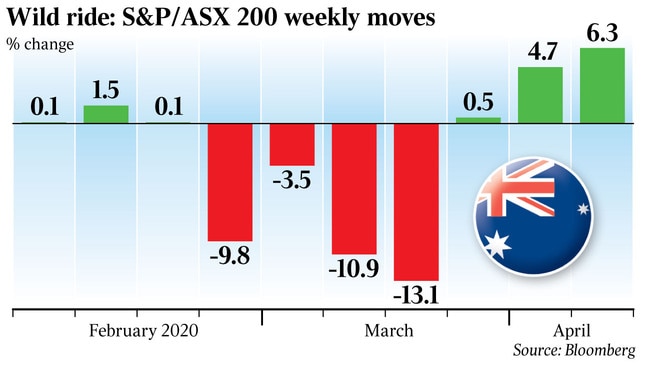

Australia’s sharemarket is also on the cusp of a new bull market, with the S&P/ASX 200 having risen 18.5 per cent from the daily closing price low of the bear market at 4402.5 points just 13 days ago. An 11 per cent gain in the past two weeks was its best two-week gain since the inception of the index in April 2000. A similar rise in the All Ordinaries index was the best performance since 1983.

But such strong back-to-back weeks in the past have not always preceded lasting bull markets as they did in 1983 and 2009. In April 2008, the S&P/ASX 200 rose 9.4 per cent in two weeks. On that occasion it rose another 6 per cent in two weeks, before diving 48 per cent to the GFC low.

While sharemarkets have responded well to government and central bank attempts to stop them falling, via fiscal and monetary stimulus, as well as promises of oil production cuts and hope of economic reopening, countries that have tried to reopen economies have had to reapply lockdowns.

The fact is that this will be a long, slow process until there are effective vaccines or “herd immunity” and the ability to rapidly test large sections of the population, which may be years away.

While markets are being buoyed by government stimulus packages, “economic damage and pessimism about the virus will dominate” this quarter as stimulus packages fade into the background, according to Westpac chief economist Bill Evans.

The dollar — now back above US62c after bouncing spectacularly off an 18-year low of US55.1c two weeks ago — is at risk of slipping back below US60c in the near term, before a modest recovery over the second half of 2020, Evans says.

He sees short-term interest rates anchored at 0.25 per cent, but expects longer bonds to come under pressure when confidence bounces late this year, and on a sharp rise in bond supply.

For Australia, Evans still sees a “deep recession” this year.

Output is expected to contract 0.7 per cent in the March quarter, 8.5 per cent in the June quarter, and 0.6 per cent in the September quarter, before a 5.2 per cent bounce in the December quarter as social distancing measures are eased, leaving growth still down 5 per cent on a year-on-year basis.

The unemployment rate is expected to peak at 9 per cent by mid-year, and would have been 17 per cent if not for the federal government’s JobKeeper package, according to Westpac.

“Beyond mid-2021, we anticipate that growth will hold around a trend pace — despite ample spare capacity in the economy — as legacies from the recession will act to constrain activity for some time,” Evans warns.

What needs to be remembered is that even with unprecedented stimulus that has exhausted much of the world’s fiscal and monetary firepower without building much new infrastructure or productive capacity, while robbing the future generation of growth as taxes eventually go higher, Australian and global growth is still expected to suffer the sharpest downturn since the Great Depression.

In the US, the extraordinary amount of share buybacks that arguably drove the record bull market since the GFC have now been shunned by many of the largest banks, travel and leisure and many other S&P 500 companies in response to public outcry, particularly from Democrat senators.

Regulators in Europe, the UK, New Zealand and Australia have told banks to cut their dividends.

After a mass withdrawal of earnings and dividend guidance in recent weeks, Australian companies are now facing their biggest falls in earnings and dividends per share (partly driven by APRA) and their biggest equity recapitalisation since the global financial crisis. This reality is by no means fully reflected in consensus estimates for corporate earnings and dividends per share, meaning that the sharemarket is a lot more expensive than it looks.

Add the fact that more than 600,000 people rushed the tax office to draw $20,000 from their super in the first week of applications — a sign that the early drawdown scheme could dramatically eclipse government forecasts of $27bn, causing headaches for industry super funds holding large amounts of illiquid assets — and the Australian sharemarket could well be getting carried away with this bounce.

There’s also considerable uncertainty for small businesses as to when and if they will qualify for the JobKeeper payments. Transmission issues could boost bad debts and unemployment.

And while the US at least has demonstrated bipartisan support to do whatever it takes in a fiscal sense after agreeing to an unprecedented $US2 trillion fiscal stimulus two weeks ago, EU finance ministers still can’t agree to bail out the nations such as Italy, France and Spain that have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.