Bumps on the road on path to normal: Aviva

Aviva CEO Euan Munro says the economy won’t necessarily go back to ‘normal’ as rapidly as the sharemarket implies.

Every crisis is different but the health aspect makes the coronavirus pandemic particularly uncertain.

While the world may have avoided another financial crisis thanks to swift action by central banks and governments on an unprecedented scale, Aviva Investors CEO Euan Munro says the economy won’t necessarily go back to “normal” as rapidly as the strong rebound in the sharemarket implies.

“There certainly are scenarios where things don’t get much better for a long period of time,” he says.

“I would say the market is probably assuming that they’re going to be substantially back to normal in 12 months and I certainly hope that’s the case, but any news that we get over the next three or four months that says ‘no, it might not be that simple as that’ is going to be a problem.

“And then of course this has been expensive and the way that it’s paid for is debt monetisation and inflation or increased taxation in the future, which will stunt growth for a period of time.”

With the global economy facing the biggest slowdown since World War II, Munro sees a significant risk of hysteresis or “economic scarring” even after widespread social distancing requirements end, particularly in the absence of “herd immunity” or an effective vaccine.

At the same time, unprecedented stimulus — particularly open-ended quantitative easing by the world’s central banks — is lifting asset prices, yet the pace of QE has already been massively tapered in the US since the stockmarket bottomed, and could be dialled up or down from here.

“They have a very limited appetite for serious declines in asset prices and the new role of central banks is not just to manage inflation, it seems it’s also to protect everyone from asset price volatility,” Munro says.

“But ultimately asset prices respond to the real economy.”

London-based Aviva Investors is the global asset management business of the insurance giant Aviva Group. Aviva has about £346bn ($645bn) of assets under management.

Aviva’s Multi Strategy Target Return Fund was among the best of its peers in the year to December, returning 10.92 per cent net of fees. This year it has “protected the downside” with a loss of 3.5 per cent on an Australian hedged basis to April 30. The MSCI All Country World index fell 14 per cent.

Munro argues that while “incredibly accommodative monetary policy” hasn’t caused inflation in the past decade because of the deflationary effects of globalisation, that’s now peaked.

“What we’re now seeing is deglobalisation. This was happening before COVID-19 and unfortunately all of the signs are that rather than COVID-19 pulling the world together, it’s to some extent pushing it apart.”

In that regard it seems as though COVID-19 has been something of a negative catalyst.

“You’ve got this much more local mindset, and localism as opposed to globalism is inherently inflationary because it leads to inefficiencies in the supply chain,” he says.

“So you’ve got disruption caused by COVID, inefficiencies in the supply chain. Obviously we’re not going to see it coming through inflation for quite a while because of the collapse of demand caused by people being confined to their homes and the damage that’s been done to the economy.”

But the supply chain could be tested and inflation may emerge after the economy picks up.

“When it picks up again, some of these things might be a problem, certainly if central banks choose to monetise the debt rather than have it cleared by increased taxation over time,” he says. “Central bank balance sheets are bigger now than they’ve ever been, so there does seem to be a tendency to want to monetise this debt.”

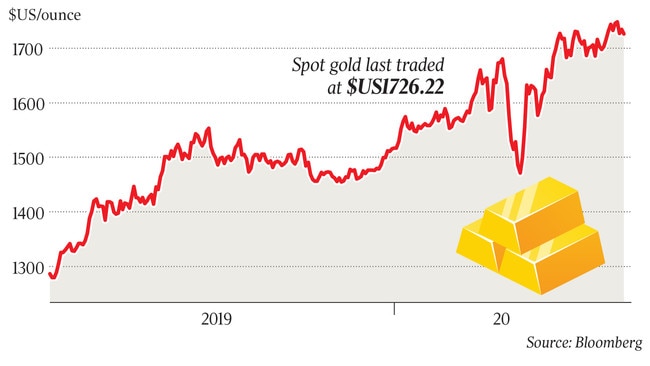

Such concerns have steered Aviva Investors to buy gold in recent months.

“So in our multi-asset portfolio — we’ve not been gold bugs — but it’s quite an interesting dynamic that in the depths of the crisis when people were scrambling for liquidity and everything was being sold, you even saw gold and silver being sold, and so we bought gold because you can’t print lots of that as you can print any other currency,” Munro says.

“It’s not major — just 4 to 5 per cent of the portfolio — but it’s something that could play over time.”

Still, he says the time’s not right to extend that inflation theme by buying into the industrial metals.

The challenge is to find assets that are priced appropriately or better still have overreacted to a “fairly bleak economic outlook”, because in his mind it’s too risky to go “all in” on economically sensitive sectors based on expectations of a robust cyclical recovery.

“We think there’s a reasonable risk that not everything that previously was cyclical will bounce back. (COVID-19) is going to change attitudes to travel, and how we work, so I think we’ve got to envisage the future that we emerge into. While it will be a faster growing future than we’re experiencing just now, it won’t be the same one that we left.”

Aviva is overweight US Treasuries — based on a view that further monetary stimulus is part of the solution — but it’s marginally underweight equities in its balanced portfolios, and prefers corporate credit to emerging markets debt because of the greater stimulus in the developed world.

But while the funds are underweight equities as an asset class, within that it has more exposure to some high beta sectors where “the baby has been thrown out with the bathwater”.

“We do think it’s an environment where smaller positions can have a big pay-off if you get it right, so we’re relying more heavily on our equity stock-picking team as we come out of this.

“There’s been a fairly generic sell-off in equities, but certain industries can pick up to normal levels pretty quickly and maybe do even better than normal, particularly the sort of technology infrastructure-type companies that are giving us access to Wi-Fi services or 5G services,” Munro says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout