Shares bounced on Thursday as Bloomberg reported that US President Donald Trump’s comments on Tuesday downplaying the urgency of a trade deal with China didn’t mean the trade talks had stalled.

But a deal continues to be delayed and it seems as though trade tensions aren’t going away.

That’s reinforcing the view that an expected rebound in the global economy after stimulus this year will be modest and easily stamped out if Trump were to keep lifting tariffs on China as planned.

Meanwhile, the Australian sharemarket remains vulnerable to pullbacks because of its high valuation, falling earnings estimates, a fragile domestic economy and a pause in policy stimulus.

Not only do US trade negotiators now expect a “phase one” deal with China before a planned 15 per cent tariff on $US160bn ($235bn) of Chinese goods starts on December 15 — suggesting it may be postponed — “the US and China are moving closer to agreeing on the amount of tariffs that would be rolled back”, unnamed officials told Bloomberg.

Tariff rollbacks would certainly help the global economy and financial risk assets, but it’s hard to believe the US would take such a big step without an enforceable agreement with China on the major issues of forced technology transfer, intellectual property protection and state subsidies.

That seems years away if it’s even possible. That was the whole point of “phased” trade deals.

The report also said recent US legislation seeking to sanction Chinese officials over human rights issues in Hong Kong and Xinjiang were “unlikely to impact the talks”, but that remained a risk.

On Tuesday, the US House of Representatives overwhelmingly approved legislation that would impose sanctions on Chinese officials over human rights abuses against Muslim minorities, prompting Beijing to threaten possible retaliation. State media said the Chinese government would soon publish a list of “unreliable entities” if the Xinjian bill passes, potentially leading to sanctions against US companies.

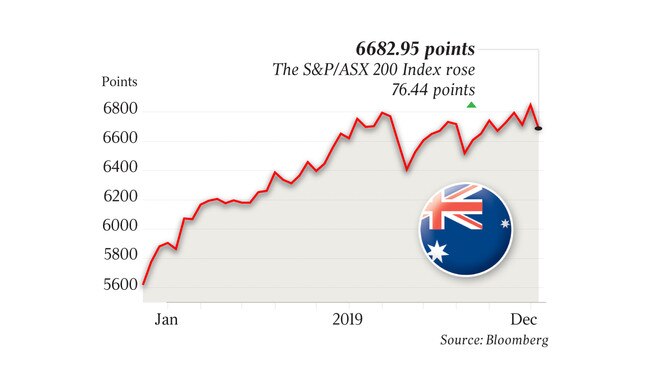

Moreover, it wasn’t just Trump’s apparent lack of urgency in reaching a trade deal with China this year that rocked global markets this week, triggering a 3.8 per cent fall in Australia’s S&P/ASX 200 index, its biggest two-day fall in four months.

The main concern on Tuesday — which drove the third-biggest one-day fall in the ASX 200 this year — was the removal of US tariff exceptions on Brazilian and Argentine steel and aluminium.

With Trump deciding to penalise these supposed allies over alleged currency devaluation, what chance would other countries have of avoiding his wrath?

Certainly, the pretext for those tariffs was more unsettling than the economic impact.

Then there was the proposed tariffs on $US2.4bn ($3.5bn) of French products in response to a tax on digital revenues that hits large US tech companies including Apple, Google, Facebook and Amazon. US Trade representative Robert Lighthizer said the agency was exploring whether to open investigations into similar digital taxes by Austria, Italy and Turkey.

And Trump threatened to hit other NATO members with tariffs if they don’t pay their share of the alliance’s bills.

Thus it seems pretty clear that US trade policy isn’t getting less hostile, even if the US is willing to walk back trade threats at times to stabilise markets.

Last week, the ASX 200 hit a record high of 6893 to be up 22 per cent in the year to date. More importantly, with earnings per share estimates having fallen 6 per cent since August, its price-to-earnings multiple hit a record high of 17.5 times, versus a long-term average of about 14.5 times.

The dividend yield hit a decade low of 4.1 per cent after 10-year bond yields hit a record low of 0.85 per cent, but bond yields may have bottomed out, barring the advent of quantitative easing.

Interestingly, the pullback in shares this week saw the ASX 200 undershoot the consensus “bottom-up” target price for 12 months ahead, but not by much relative to its history.

Normally the index trades well below the target price, but as indicated by the abnormally high PE ratio and unusually low dividend yield, this has been an extraordinary year, thanks to what has easily been the biggest co-ordinated central bank policy backflip since the global financial crisis. In late July, the index was a record 294 points above the 12-month target as central banks pivoted towards cuts. But it dropped to minus 223 points as the index fell 7 per cent from its July 31 peak.

With the RBA and the federal government putting policy stimulus on hold, past stimulus failing to get economic traction and earnings per share estimates trending down, the unusual period of extreme overshooting of the index above its target price this year is probably over — at least until the start of some major new policy stimulus such as quantitative easing or faster fiscal stimulus.

If the US were to unexpectedly go ahead with the December 15 tariff increase, a more substantial undershooting of the index below the consensus target would become more likely.