Buckle up, credit crunch is here

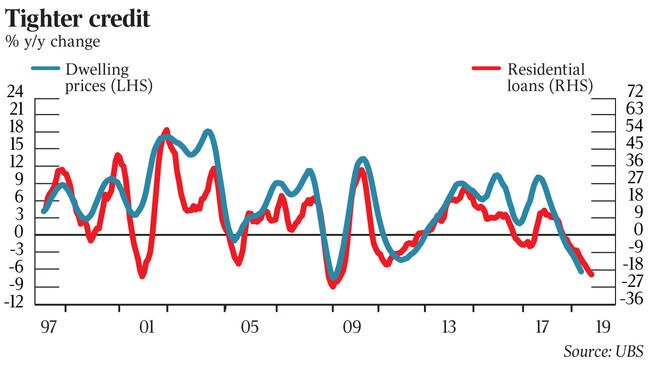

George Tharenou of UBS says credit tightening is just beginning, with negative implications for house prices, growth and jobs.

George Tharenou says credit tightening is just getting started, with negative implications for house prices, growth and jobs that will force the Reserve Bank to start cutting interest rates again.

Like anyone who dared question the veracity of Australia’s home borrowing binge and the longevity of the associated housing boom, Mr Tharenou has had his fair share of pushback.

But so far the chief economist of UBS Australia has been right on the money.

Now, while the Reserve Bank and the majors are convinced a 25 per cent dive in new home loans since mid-2018 is mainly due to a lack of demand, he says it’s all about supply.

Moreover Australia could be experiencing a “credit crunch” — a rapid fall in the availability of credit.

As far back as 2015, Tharenou warned about the high and rising number of new mortgagees surveyed by the “UBS Evidence Lab” who said their applications were “not factual and accurate”.

The results were “disturbing” given the housing market re-acceleration at the time, together with record household leverage and the extent of the banks’ exposure to home loans.

Fast forward to the banking royal commission and the rest is history.

Many tried to predict the peak, but UBS nailed it, telling clients in April 2017 to “ring the bell” on the boom just a few months before the white-hot Sydney and Melbourne markets rolled over.

Then, in a worrisome note in September 2017, he said borrowers were finding it easier to get their loans approved despite APRA’s “macroprudential” crackdown on lending standards.

Speaking to The Weekend Australian, Tharenou said his warnings about the housing market caused “a lot of conjecture and controversy”.

But his team was convinced its credit-tightening thesis would play out. “We didn’t believe the consensus view that the housing market would keep rising, the economic outlook would keep improving and interest rates would normalise,” Tharenou says.

“We thought that behind the scenes there had been material easing of lending standards.”

Last November, UBS upped the ante on its credit-tightening thesis, warning the outlook for the housing market was “deteriorating rapidly”.

Further credit tightening was inevitable post-royal commission as borrowers faced debt-to-income limits under comprehensive credit reporting, and potential changes to negative gearing and capital gains tax should Labor win the federal election.

“That thesis has played out with record falls in house prices, driven by a reduction in borrowing capacity amid a tightening of lending standards which we think will continue,” Tharenou says.

“We predict the value of new home lending will fall 30 per cent and we’re already down 25.”

Housing was the starting point for his below-consensus economic view and when the RBA shifted to a “balanced” interest rate outlook early last month he predicted two interest-rate cuts this year.

After initially predicting a 10 per cent fall in national average house prices, he widened that to 14 per cent (double the fall so far) after very weak home loans data last month.

Key to his view is a “negative wealth effect”, where households stop reducing savings.

“They don’t even have to increase savings to slow consumption growth to the rate of income growth. All that happened in the national accounts this week was consumption slowed to income.”

He rejects the RBA’s view that because house prices rose 75 per cent in Sydney and 60 per cent in Melbourne in the five years from 2012 and are now down about 10 per cent, everything is fine.

“That’s true for bank capital and mortgage areas and negative equity, so this is not a financial crisis where everyone is behind on their mortgages and the whole banking system goes crash.

“But when house prices started declining, people started lowering their consumption. So you don’t even need a negative wealth effect. If you get one, you’re in a ‘credit crunch’ scenario.

“What flips you over to a credit crunch is consumption goes below income.”

On the “growing tension” between the strong labour market and softer growth data Rreserve Bank governor Philip Lowe complained of in a speech this week, Tharenou has a simple explanation.

“The disconnect between economic growth and jobs is just a simple lag, as it has always been.”

If so it could be risky for policy makers to wait for unemployment to start to rise before adjusting policy.

“The problem with that framework is that by the time unemployment rises, you’re probably already 12 months into an economic downturn,” Tharenou says.

“I would say we’re already six months into a slowdown because second-half growth was less than 1 per cent annualised versus nearly 4 per cent in the first half.

“That’s a very sharp slowdown and private demand — the bit that the cash rate affects — was zero. So to me the extent of the slowdown in growth is so sharp that it’s definitive that the unemployment rate will rise over the next year.”

And he says it’s important to note that the labour market has already stopped tightening.

Employment growth has slowed for a year and unemployment hasn’t fallen for five months.

“It suggests that slowing growth six to 12 months ago was already consistent with a slowing rate of improvement in the jobs market.

“Deterioration will probably take another three-to-six months to come through in the data and that probably doesn’t happen quick enough to see the RBA cut, but the economic growth data was so weak that you know the jobs market will roll over.”

The other key element of the national accounts data was that income slowed.

“We had booming jobs growth a year ago which is moderating, and there was a modest pick-up in household income which is the primary focus of the RBA as it expects rising income to offset falling house prices and the impact on consumption will be neutralised,” Tharenou says.

“They still have that view but I think that was challenged clearly by the national accounts data. You’re just not seeing any translation of jobs growth to income growth.”

In the absence of policy stimulus he says it’s fanciful to think the economy can rebound to a 3 per cent annual growth pace this year as the RBA expects.

A continued ramp-up in the public spending that kept the economy above stall speed in the second half won’t prevent a slowdown to well below its potential growth rate in coming years, even with potential fiscal stimulus in the federal budget due on April 2.

Tharenou already expects household tax cuts of $8 billion to $10bn — near the top end of market estimates — plus $5bn in fiscal transfers from the budget.

Commodity price gains in the past year mean the budget is tracking well ahead of expectations and he expects the government will try to return it to households via tax cuts and spending to support the consumer in this period where they probably want to save more because house prices are falling.

“But even with that stimulus, it’s insufficient to offset the weakness in housing and the negative wealth effect on the consumer, so I think the RBA still cuts, even with moderate fiscal stimulus.”

His main concern is that a large fall in housing construction activity has only just begun.

“The December quarter was the first quarter — from a record high — where construction activity started to fall and it’s likely to accelerate to a double-digit year-on-year pace in coming quarters, given the collapse in building approvals (down about 30 per cent),” Tharenou says.

“Second is the renovations market, where lending has absolutely collapsed — down more than 30 per cent — and people are moving less and borrowing less for consumer durables.

“So there’s a much broader impact story about the savings rate across the economy, but there’s also the direct construction impact, the renovation impact and housing turnover impact.”

In his view Australia is well on the way towards a credit crunch.

“My framework here is that the regulatory tightening is accelerating, so the only effective policy lever available in the near term to stimulate the economy is the cash rate,” he says.

“There’s a view that the royal commission was benign because it didn’t change law, but we never expected it to. All that’s happening is that the loans not compliant with responsible lending laws and regulation are stopping and people’s maximum borrowing capacity has been reduced.

“The problem is the rate of change is accelerating and there’s still a long way to go. So there are some who think we are already through this process, but we disagree. We think we’re only about half-way through.”

This is before a potential federal Labor government stops negative gearing on investment properties.

But Tharenou isn’t surprised there has been no pre-election rush for investment property.

“The key risk around negative gearing and capital gains tax changes under Labor is that it reduces borrowing capacity further.

“The vast majority of investor loans are used to purchase established properties, so removal of tax breaks for established properties will have a large impact on the willingness of borrowers to buy established properties.

“The second element is that if you buy new property after the policy comes in, you get the tax break, but the moment they try to sell, it’s an established property.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout