In some areas, the decline is between 15 and 20 per cent. Combine that with the latest catastrophic fall in building approvals, and the long-awaited acceleration in the downturn is now fully underway.

In the last few months, there have been small falls in the food sector, but inflation masked larger but manageable falls in other retail areas, including appliances and clothing.

As set out below, a series of forces that have combined to accelerate those downturns, and those forces are likely to continue for some time.

It will require a wake-up call from both politicians and the Reserve Bank to change the direction.

And for the Reserve Bank that won’t be easy because inflation is not only well and truly embedded in the economy but rising and, like the US, is currently being driven by the impact of higher wages growth on services costs and prices. That wages pressure will continue until it's broken by a severe downturn.

Meanwhile, many service companies are still able to raise prices — efficiency becomes secondary. But the game will change in coming months.

I was first alerted to the downturn acceleration by people in the transport industry. Then I checked with the network of floor-people.

These are the same people who three years ago told me sales were booming when the official figures said there was a slump. The Reserve Bank ignored the comments of me and others at the time and didn’t get outside their Martin Place bunker. They relied on out of date official figures, leaving rates too low for too long.

Now, because the 2023 downturn acceleration has occurred in the last two weeks of May, the fall may not be seen in official figures for another month or so.

But the ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence has now spent thirteen straight weeks below the 80 mark — a clear warning of trouble ahead.

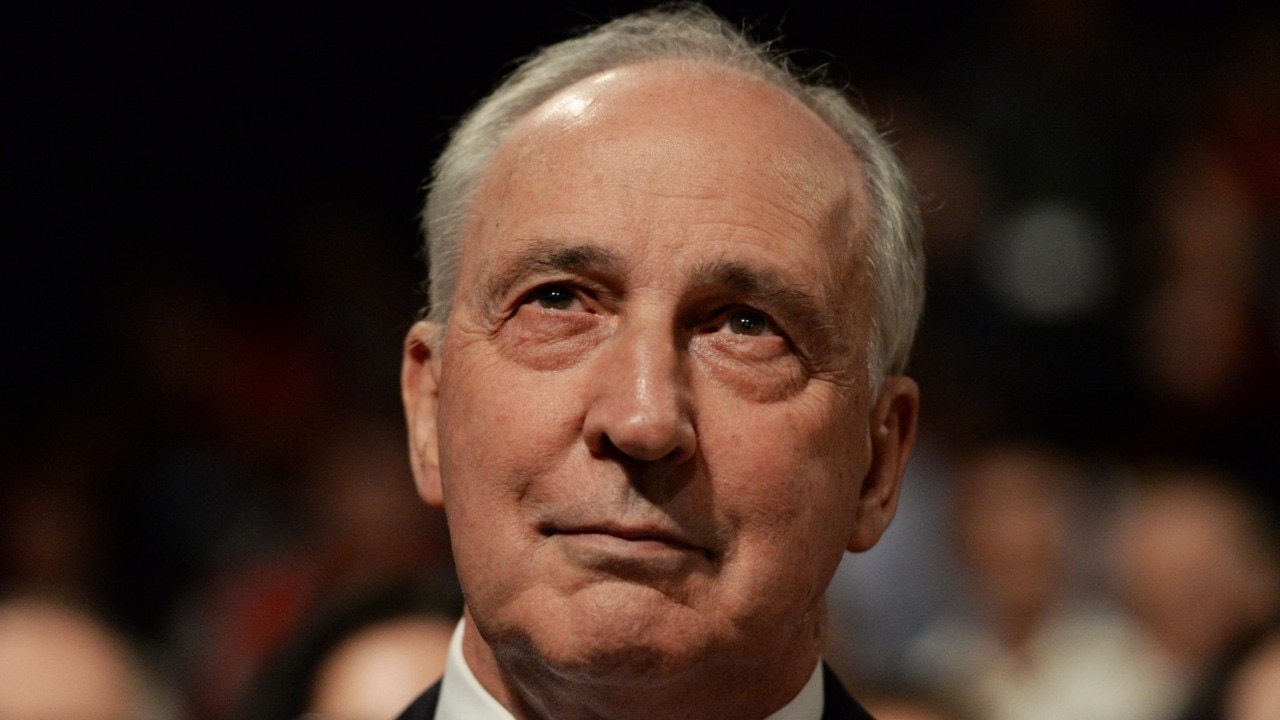

The last time the consumer confidence index spent at least thirteen weeks under 80 was during the 1990-91 recession — the recession which then treasurer, Paul Keating, described as “the recession we had to have”.

The May 2023 retail downturn was triggered by the combination of events:

• Adjusting for inflation, Australian wages have fallen 3.2 per cent over the last year and 7.2 per cent since their peak. There have been few times in our history where there has been such a big fall in real wages. Middle Australia is hurting.

• In May, a vast number of heavily mortgaged householders actually received their interest bill as they converted from fixed low rate borrowing terms to today’s rates. They knew it was coming but receipt was a deep shock.

• There have been volleys of misleading statements about what politicians are going to do to reduce energy prices, but that was all nonsense. Their disastrous policies over the last two years are exploding power bills which really hit middle income Australia. Any relief was delivered to the lower income areas, not middle Australia.

• The Reserve Bank further increased interest rates in May, and there was speculation of more to come. Whether the speculation was right or wrong was irrelevant. It increased fear.

• The fall in consumer demand has been delayed by the unexpected stabilisation and even increase in house prices despite higher interest rates. Meanwhile, potential buyers of new houses are too scared of builder failures to place orders, so the shortages will continue.

• The housing shortage means that renters are often being squeezed in a more brutal way than those with mortgages. Recently, the Victorian government decided that renters should be given an extra kick with a “rent tax” levied via a landlord tax. And an “educational tax” was levied on middle income Victorians (by taxing independent schools) who want to give their children a better education. Both those measures will increase inflation in Victoria.

• When the federal budget came out, a series of low-income people were given aid. But those in middle Australia, the wealth creators, were given nothing and told to suffer because “you are affluent”. It was a cruel blow.

• Australians coming to the supermarkets are met with regular price rises, which are being offset by people buying cheaper goods. The trend towards buying lower priced goods is spreading in all retail markets.

• During Covid-19, people did not travel overseas and spent much of that money locally, including home improvements. Now among the affluent, that “local” spending money is being outlaid on overseas travel.

• At the moment there is a shortage of skills, but as workers in retailers and their suppliers see sales fall sharply, they know that the survival of their enterprise will depend on labour shedding.

Many under mortgage stress are meeting their repayments via the gig economy, often in the retail sector, so are very vulnerable to this downturn. And those that study the Canberra political manoeuvrings know that the government wants to hit them harder by restricting the gig economy to make it more difficult to supplement extra income.

At this stage because the fall has been sudden and only for about two weeks, naturally retailers want more time before pronouncing a downturn. But the one thing the budget got right was forecasting a sharp fall in the Australian economy in 2023-24, despite strong mining and agriculture.

It has started a little earlier than expected.

The stock market has been driven by interest rate trends, so the accelerated downturn is good news because it will curb rate rises. But in terms of the looming profit blows for many enterprises, the market has ignored the budget predictions and is not priced for this downturn.

The dam has burst. Suddenly, in the last two weeks, large areas of the retail trade have turned down sharply.