The great High Court lottery

We know very little about how the new judges will interpret the constitution.

The selection of two judges to Australia’s top court came with no Senate hearing and none of the national soul-searching that has accompanied Donald Trump’s appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to the US Supreme Court.

But Scott Morrison’s announcement on Wednesday of two new High Court judges will arguably have an even more profound impact on the direction of Australia’s top court.

Melbourne-based Federal Court judge Simon Steward, 51, will replace judge Geoffrey Nettle, also from Melbourne, when he retires on November 30.

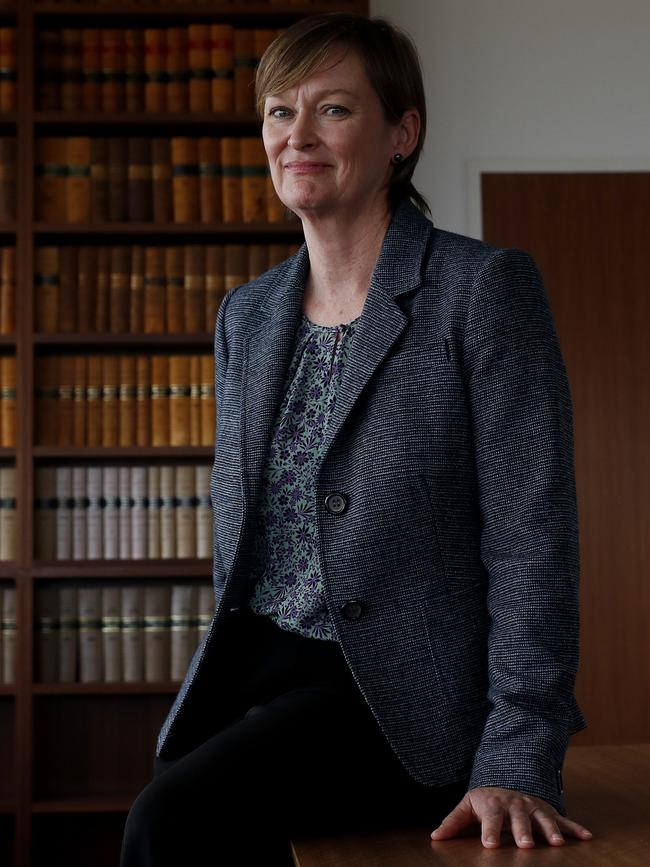

Sydney-based Federal Court judge Jacqueline Gleeson, the eldest daughter of former High Court chief justice Murray Gleeson, will replace Virginia Bell, from Sydney, when she retires on February 28.

The appointments preserved the gender and geographic composition of the court — but will shift the balance of the High Court in another sense.

Trump has managed to appoint three judges on a bench of nine.

When Justice Gleeson, 54, takes her seat, the Coalition will have put the majority of the seven’s judges on the bench. The pair join Michelle Gordon and James Edelman as Coalition picks.

Chief Justice Susan Kiefel was a John Howard choice, while Stephen Gageler and Pat Keane were given the nod by Julia Gillard.

There was no widespread popping of champagne corks within the legal community to accompany this latest round of appointments. Instead, there was belated soul-searching by some lawyers, who were concerned they were not necessarily the best-credentialed for the job.

The government’s selection process kicked off six months ago. But it was shaped by a controversial High Court decision delivered in February.

The High Court ruled 4-3 that Aboriginal people — even those born overseas — could not be considered non-citizens under the Constitution. The judgment, involving convicted criminals Daniel Love and Brendan Thoms, was viewed as an “activist” decision that created a new category of Indigenous citizenship.

Conservative MPs were dismayed that all three of the Coalition’s most recent High Court picks — Nettle, Gordon and Edelman — had formed the majority with Bell in that decision.

The majority had ignored the view of Chief Justice Kiefel, who said such a decision would “usurp the role of the parliament”. It was not up to the judiciary to decide whether the men were “aliens”, as this involved “matters of values and policy”, she said.

Those in conservative quarters were determined the next High Court picks would be “black letter” lawyers.

Australian Catholic University vice-chancellor Greg Craven says the Coalition is notoriously poor at picking constitutional conservatives for the High Court.

He says it is not proper to make political appointments to the High Court — in the sense of appointing party people who will politically favour government projects.

However, governments are “absolutely entitled” to have a theory of constitutional interpretation and appoint judges who subscribe to that same view.

“If you’re a Liberal conservative government, you really should be appointing people who are going to interpret the Constitution according to the fundamental intention behind it, as displayed by the words,” he says.

Instead, he says, those on the conservative side of politics tend to get distracted by the wrong questions: “Is this person one of us, do they move in the same social milieu, are they in the same club as me, do they know the same people as me, did they did go to school with me or my friends?”

Craven says the key question should be how a person interprets the Constitution — because that will “preprogram” their answer to constitutional questions.

“The key question is, are you interpreting the Constitution as an intentional textual document, or do you see it as like Pride and Prejudice — it means what you think it means according to your own taste?” he says.

Craven says that because conservative governments don’t tend to “think that through”, the results they get can be “completely unanticipated”.

Sometimes they pick brilliant commercial or taxation lawyers who are untested on constitutional law, so it is a “complete lottery” whether they will turn out to be adventurous in their interpretation of the Constitution.

The classic example, he says, is William Deane, who was selected by the Fraser government. “Sir William Deane is a brilliant lawyer, he is a wonderful man and he came with impeccable legal credentials, but once he was on the High Court he proved to be one of the most radical judges,” he says.

Craven says there is no question that both Steward and Gleeson are brilliant lawyers, but he does not have any particular confidence in predicting their constitutional views.

“It’s perfectly possible,” he says, that in six years people will be saying that the conservatives had an opportunity to produce a constitutionally conservative court but “didn’t grasp it”.

It is understood the process to reach cabinet agreement on the names was arduous.

Steward is a renowned tax expert from Melbourne. His appointment has been predicted since February and he has the backing of conservatives. However, he has been on the Federal Court for less than three years. A former solicitor with King & Wood Mallesons, Steward is a history buff, an aficionado of Winston Churchill, and a lover of antiques and fine art.

He is a former head of the tax bar and one of three barristers, along with barristers Stuart Wood QC and Michael Wyles QC, who led the push for the Queen’s Counsel title to be revived in Victoria for silks (which had been dropped in favour of senior counsel).

Wood was among those celebrating with Steward on Wednesday at Italian restaurant Becco in Melbourne. They were there with fellow Federal Court judges and barristers David Batt QC and Eugene Wheelahan QC.

Batt says Steward has “all the qualities that are expected of a great High Court judge”:

“He is deeply learned, highly intelligent, diligent, courteous, impeccably fair and efficient”. Batt says even if Steward has not practised widely in a particular area, he is “such a technically skilled lawyer and so hard-working that he will be across anything that comes before him”.

Steward, whose father was also a lawyer, was admitted as a lawyer in 1992 and, according to Porter, became the first from his graduating law class to become a silk in 2009.

Gleeson is seen by many to have been a capable Federal Court judge, but not spectacular. Some privately accuse the government of “dropping the ball” with her selection and say her appointment has been received with “sadness” on Sydney’s Phillip Street.

“You’ve had the wife of a former High Court judge (Gordon, who is married to former High Court judge Ken Hayne) and now the daughter of a former High Court judge appointed to the High Court,” one lawyer says. “It says everything that is wrong about the Liberal Party.”

There is speculation that former prime minister John Howard — who nominated Gleeson’s father as chief justice — lobbied for her appointment.

However, Gleeson is well-liked and believed to be well-regarded among Federal Court judges, who sit together on appeals.

She was the dux of her high school at Monte Sant’ Angelo Mercy College in North Sydney in 1983 and became a lawyer in 1989. She joined the NSW bar in 1991, detoured to practise as a solicitor with the Australian Broadcasting Authority and the Australian Government Solicitor, then returned to the bar in 2007.

She was the Abbott government’s first judicial appointment, in 2014, and said at her swearing-in that her mother had been in charge of her wellbeing and development and could “justly take credit for any success of mine”. Gleeson said she emulated her father’s self-discipline.

The High Court will not have anyone with strong criminal trial experience when Bell — regarded as the court’s criminal law expert — retires.

Attorney-General Christian Porter told reporters that both judges have “impeccable records and skills for the High Court”.

“They are outstanding judges, they have been outstanding barristers, they are outstanding members of the legal and broader Australian community,” he said.

Candidates who were strongly favoured in legal ranks were ruled out during the selection process.

NSW Court of Appeal judge Mark Leeming was viewed as a shoo-in in terms of his legal expertise — and his black-letter legal views. He even had the backing of some NSW Liberals, however, a factor counting against him was his perceived closeness to former High Court judge Dyson Heydon, found by an independent investigator to have sexually harassed at least six former associates.

The fact that Leeming and NSW Court of Appeal president Andrew Bell were part of a majority decision that allowed the Black Lives Matter protest to proceed in Sydney during the pandemic also apparently counted against both.

Another Federal Court judge, Jayne Jagot, who has been on the bench longer than Gleeson and is extremely well-regarded, also missed out. She is married to Peter McClellan, who led the child sexual abuse royal commission, and is viewed as closer to Labor.

Women Lawyers Association of NSW president Larissa Andelman says while her organisation is delighted with the appointments, it would have been a positive if the Attorney-General had consulted with peak body Australian Women Lawyers. “We would have liked to have seen a majority of women on the High Court for the first time,” she says.

South Australia, which has never had a High Court judge, missed out again. The opportunity for cultural diversity on the bench was also overlooked.

Institute of Public Affairs executive director John Roskam says the appointments will “curb the High Court’s adventurism”, and after the “radical Love and Thoms decision” will “redress the balance on the bench”.

However, it seems Roskam, like others, has been slow to learn the lessons of Love and Thoms — that it is difficult to predict how judges will behave once they reach the High Court.

The Morrison government will be judged in the future on whether it has stacked the High Court with adventurist judges — and whether it has appointed outstanding intellects who will leave a positive mark on our legal system.