Super funds Rest, Hesta backing litigation funders ‘targeting their own investments’

Australia’s largest super funds are investing millions of dollars in both litigation funders and companies they are targeting in court, amid calls for a crackdown on ‘vulture’ firms reaping huge profits from the government’s ‘light-touch’ to class actions.

Australia’s largest super funds are investing millions of dollars in both litigation funders and companies they are targeting in court, amid renewed calls for a crackdown on international “vulture” firms reaping huge profits from the government’s “light-touch” approach to class actions.

The revelation comes as revenue for the nation’s litigation funding market quadruples to more than $200m, with Australia becoming the second largest forum for class-action suits, trailing only the US.

Critics have ramped up calls for tighter regulation of litigation funders as profits skyrocket, but many doubt that meaningful reform can be achieved under a Labor government with close ties to class-action firms.

One of Australia’s largest super funds, Rest, chaired by former Victorian deputy premier James Merlino, is the second largest investor in litigation funder Omni Bridgeway, holding at least 9.48 per cent, worth about $26.78m.

But Omni Bridgeway is currently funding class actions against various organisations – such as Toyota, the Commonwealth Bank, AMP, Brambles, Downer EDI and Mesoblast – in which Rest has more than $800m invested.

Similarly, as of July this year, Hesta had 3,910,507 shares in Omni Bridgeway, valued at about $3.715m. As of last December, the fund had $2.32bn in companies against which Omni Bridgeway has funded or is currently funding class actions.

A Rest spokesman said all of the fund’s investments were “made on their own merits according to our members’ best financial interests”. Hesta declined to comment.

Menzies Research Centre executive director David Hughes said it was not in members’ interests for their super fund to be backing a litigation funder which is targeting the fund’s other investments.

“It’s a conflict in the sense that it’s not in the members’ interest to be investing in a litigation funder if that litigation funder is targeting other companies that the fund has a holding in,” he said. “It’s basically using your investments to target another investment to the detriment of the other investment.”

He said super funds were investing in litigation funders because of the “immense profits” they brought in, but those profits were at the expense of “big listed Australian companies” that the super funds also had holdings in.

“Those profits are coming at the expense of those companies and the returns for the shareholders of, say, BHP, who have been the subject of a class action,” he said. “Litigation funders would return strong investments, I’m sure, to Hesta or CBUS. But if they’re targeting, for example, BHP, who the super fund also has a holding in, it’s coming at the expense of the returns there.”

He said litigation funders that made the most of the Australian legal market – where there was a “very low bar” for commencing class actions – were damaging the justice system and those who interacted with it. “Litigation funders often operate internationally,” he said. “They have a lot of capital they bring into the Australian market, and leverage it in class actions because we have a lower bar than overseas.”

He said litigation funders backing Australian class actions were often also exploiting plaintiffs of the case by taking a large cut of the settlement payment.

The Menzies Research Centre last month released a report finding for class actions settled from 2013-18. Those backed by third-party litigation funders returned a median of just 51 per cent of the settlement to claimants. “Meanwhile, in cases pursued by claimants without a litigation funder partner, a median of 85 per cent of the settlement was returned to them,” the research found.

The report recognised a “growing problem” where “favourable conditions and low oversight mean that Australia is considered the honey pot of extraordinary investment returns by those in the third-party litigation industry when they invest in class actions”.

It said there was a “clear structural incentive” for litigation funders to invest in Australian class actions because of limited regulation. “Our system limits risk through the availability of funding mechanisms like common fund orders and group costs orders, lacks transparency for class members over the effects of litigation funding agreements, and holds litigation funders to a lower standard than other firms providing financial assistance to customers,” the report reads.

“These incentives for litigation funders can overshadow the legitimate rights of class members to access justice.”

The report recommended a 30 per cent cap on litigation-funder proceeds from settlements or awarded damages, and suggested class-action mechanisms should be harmonised across jurisdictions to “reduce forum shopping behaviour”.

The former Coalition government sought to crack down on class-action suits in 2020, following recommendations from an Australian Law Reform Commission inquiry, which found the number of matters funded by litigation funders grew from 40 per cent of finalised Federal Court class actions between 2008 and 2012 to 77 per cent in 2017 and 2018.

Reforms that passed parliament required litigation funders to hold an Australian financial services licence and comply with the managed investment scheme regime. The Coalition also attempted to restrict class-action funders and lawyers to a maximum 30 per cent of any payout. This proposal lapsed after the 2022 federal election. Earlier reforms were also unwound once Labor took power, and after the Federal Court ruled in June 2022 that funded class actions were not managed investment schemes, and fell outside the Corporations Act’s regulatory scheme.

Liberal senator Jane Hume said international firms were targeting Australia “because of our light-touch government regulation around them” which allows them “to make high returns at the expense of ordinary Australians”.

“Access to justice is profoundly important, but the problem is the scales have tipped so far that Australia’s justice system is now being seen as a highly lucrative asset class,” Senator Hume said.

“There’s no real incentive for actual justice, only financial settlement, and often for grievances that are confected by the lawyers and the litigation funders themselves.”

She said this had a “warping effect” on the community, including super funds, which meant that “we all pay more”.

“It also has a warping effect on the effective functioning of our courts and court legal system and the litigants themselves who, more often than not, receive less,” she said.

“The courts are clogged up, which means that anyone trying to access our legal system finds their processes slowed down and costing more.”

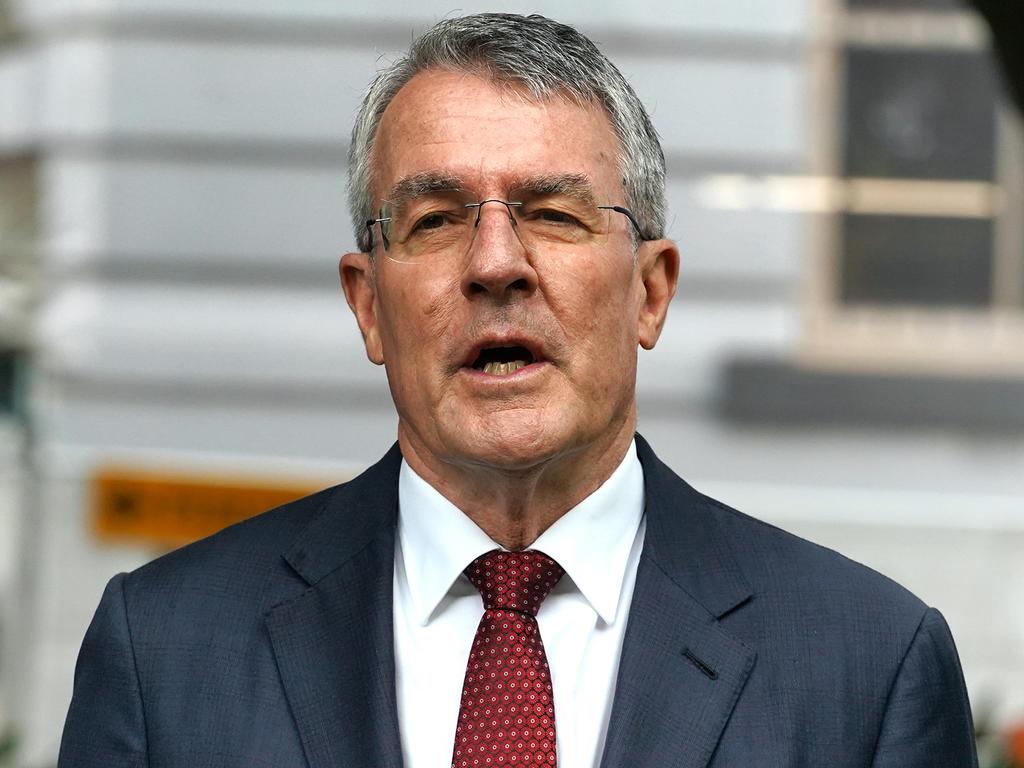

When winding back the Coalition reforms in 2022, Assistant Treasurer Stephen Jones described the laws as a boondoggle.

Senator Hume said: “This is no surprise because Stephen Jones is a former lawyer himself. Those Labor firms – Maurice Blackburn, Slater+Gordon – are now in on the action. I would imagine there would be an awful lot of pressure on the Labor government from the Labor law firms not to change the regulations, because there’s a lot of people making a lot of money.”

Maurice Blackburn has donated $2.49m to Labor and union causes since 2019-20, according to the Menzies Research Centre report. Slater+Gordon contributed $1.39m over the same period.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout