Dylan Voller case a test for social media defamation

Are Australian courts prepared for the hundreds of social media defamation cases proceeding through them?

Are Australian courts prepared for the hundreds of social media defamation cases proceeding through them?

The liability of search engines is still not entirely clear. Those who tweet have been held to be liable. If you put a link into your tweet or article and the link is found to be defamatory, are you liable?

The courts often look at cases decided long before the internet for guidance. Should this new social media environment be looked at through fresh eyes, not limited by precedent?

How is it just to have a one-year limitation period for hard copy publications, but none if the same article is online?

An interesting case looking at one of these issues came before the NSW Supreme Court recently.

The landmark Voller case, currently in the NSW Supreme Court, highlights the need for an urgent and full-scale review of Australia’s defamation laws.

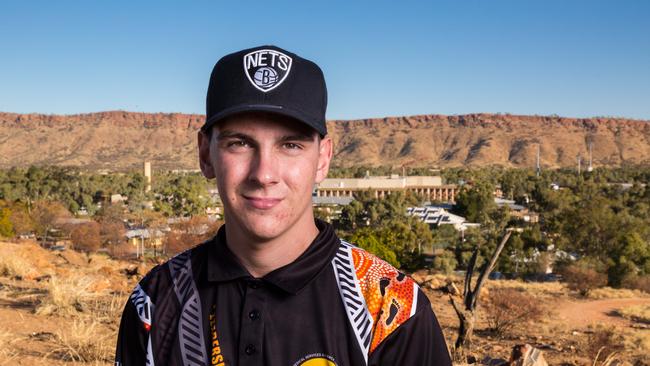

Dylan Voller, a youth detainee in the Northern Territory, is suing three media organisations for comments made by members of the public on their Facebook pages.

Notably, Voller is not suing the media outlets for the content of the articles themselves, but has instead argued that the media companies ought to be liable for the defamatory comments on their Facebook pages.

It’s a novel idea to be able to sue the media for comments made by the public on their website or social media pages. It is timely the courts are looking at this now.

Allowing the public to comment on articles online could be considered the most visible form of participation in journalism and an effective way for media companies to engage with audience, providing opportunities for the public to have a voice.

However, allowing online comments is not without risk. Indeed, doing so could expose media companies to claims of online defamation, which may result due to a user posting defamatory statements through an online medium, such as a website comments section or Facebook page.

Historically, if an individual wanted to sue a media company with respect to comments posted on their Facebook page, or some other online platform, the individual would first need to give the media company notice of the existence of the defamatory comment, and provide the media company an opportunity to remove the comments.

However, that may all change in light of the Voller case.

Voller did not give notice to these media companies. However, he has argued that the media companies chose to be proprietors of Facebook pages for their own commercial benefit, invited and encouraged readers and viewers to use their Facebook pages and knew or should have known there was a “significant risk of defamatory observations” in the comments of each post.

If the NSW Supreme Court agrees with Voller, the consequences of this case could change everything, not just for media outlets, but for all Facebook page owners, who may be deemed liable for comments posted on their posts and pages.

Foreseeably, Facebook page owners might stop permitting comments on their posts, as they would be required to consistently monitor the comments, creating an extraordinarily onerous burden just to mitigate against the liability of being sued.

If the court agrees with Voller, Facebook page owners, particularly those with high levels of engagement and traffic, will be faced with a stark choice — pay someone to rigorously monitor their pages for defamatory content or to remove the right for the public to comment freely on posts.

Will social media page proprietors be expected to stand guard at the gates of their websites or social media, carefully disentangling considered and valid public commentary from false and defamatory statements?

Herein lies the risk of curtailing genuine free speech for the need to stop commentary that would put proprietors at risk.

We know that in the age of social media, everyone is considered a publisher for the purposes of Australia’s defamation laws, leading to a sharp rise of social media-related defamation cases being heard in courts, including many of a trivial kind. However, the Voller case will go one step further.

If Voller succeeds, not only will every social media user be a publisher in the eyes of our laws, but indeed, every social media user becomes a publisher on behalf of the relevant page owner on which the user is posting.

Peter Bartlett is a partner at Minter Ellison.