Coronavirus: ‘Civil liberties have been put at risk’

Emergency measures to fight COVID-19 have been imposed without sufficient oversight from parliament, creating a potentially dangerous precedent.

Emergency measures to fight COVID-19 have been imposed without sufficient oversight from parliament, creating a potentially dangerous precedent that could be used to erode civil liberties in the future.

Legal experts say it is concerning there have been so few parliamentary sittings during the crisis and a closer look is needed at emergency processes to ensure proper accountability.

The comments come amid debate over a proposal by Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews to extend the time limit on emergency powers from six to 18 months.

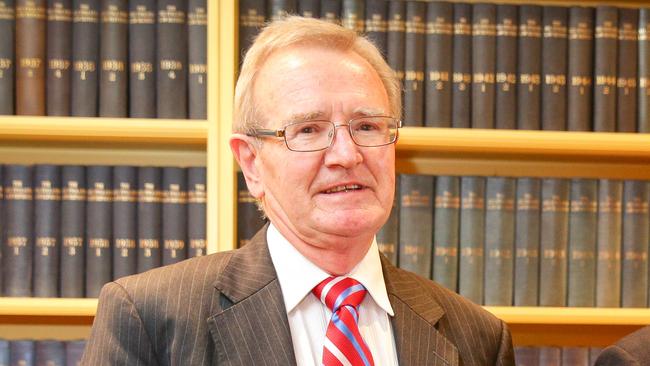

Rule of Law Institute of Australia president Robin Speed said there had not been proper checks and balances applied to lockdown measures, such as the curfew and 5km travel limit in Melbourne.

He said health advice should have been released to justify the steps and debate in parliament.

“Who says 5km is reasonable?” he said. “Where is the evidence? If you had to debate the matter in parliament, you would expect someone to stand up and say we think it’s necessary for health reasons, this is what our expert says and 5km is good, not 6km or 7km.”

The 76-year-old, who has cancer, said the nation’s leaders were supposedly focused on caring for vulnerable people like him. “The worst thing for an old person is to die alone. Should an old person die alone, away from their relatives or not?” he said.

“It’s a really major issue for me, and anyone my age. If you come along and ask me, I would not want that to happen. That’s a community matter that should be debated. Where is the forum for debating it?”

The fact there had been so few parliamentary sittings and no debate by MPs eroded public trust, he said. “I think it creates the most dangerous precedent. I am alarmed that in Victoria there have been relatively no protests about what has happened.”

Mr Speed said he did not believe the time limit on emergency powers should be extended to 18 months and to do so would be a breach of the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities, which require any restriction on rights, such as free movement, to be reasonable and justified.

Constitutional law expert Cheryl Saunders said once the crisis had eased, an examination was needed of the balance between enabling governments to respond swiftly, and accountability.

If Australia experienced more emergencies, its procedures would likely involve more parliamentary oversight, she said.

“When this has finally died down, a proper look at what are our emergency procedures and how we can both deal with emergencies and ensure appropriate checks and balances would be a good thing,” Professor Saunders said. She said it was a concern that parliaments had not met a lot during the crisis, although it was understandable. A fallback was needed if MPs could not meet physically, she said. Changes were made last week to enable federal MPs to participate in debate remotely but not to vote.

“There is nothing like having them face each other across the chamber,” she said. “Facing each other across Zoom … (or) with a smaller number of people is not the same thing. So I’m not suggesting it as a replacement, but I do think we need to work out how these things can be done without sacrificing parliament.”

University of NSW professor of law Rosalind Dixon said international law required that any limitations on rights were necessary, proportionate and subject to continual review. Premiers fronting daily press conferences was one oversight mechanism, and the courts and parliaments also had to continue to operate. As much health advice should be released as possible to justify the decisions that were being taken, she said.

“Courts have adapted in a really impressive way and I think parliament should also adapt.”

Deakin Law School lecturer Bruce Chen said if the Andrews government tried to introduce changes to allow a declaration of a state of emergency to be extended for up to 18 months. it would risk “a slippery slope”.

“The making of a declaration is essentially a discretionary executive power, wielded by the Minister for Health,” he said. “Given this, the state of emergency, and the significant powers it can enable, are restricted and temporary for good reason.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout