Calls for federal body to handle allegations against judges grow louder

A federal judicial commission is needed for when those who pass judgment in Australia go awry.

The emotive scene took place in the Family Court of Western Australia but it was the judge who was weeping, rather than the litigants.

Justice Gail Sutherland, now Chief Judge, told those gathered in the Perth courtroom that August day two years ago that she had decided to disqualify herself from hearing their case because she could not be seen as impartial.

“Excuse me,” she said, trying to fight back her tears. “The reality is that all of my colleagues, if they’re not already disqualified, are in the same boat as myself.”

It was just another bump in a 14-year legal battle between a Perth real estate agent, known as “Mr Charisteas”, and his ex-wife that now looks likely to land in the High Court. The pair, who have three adult children, were originally fighting over a $12m property pool. Most of that money is now gone — a “king’s ransom” paid to the lawyers — but plenty of disquiet remains about the way the case has been handled.

‘Inappropriate’

Sutherland’s unusual display of emotions back in 2018 occurred during an appeal by the husband, known as “Mr Charisteas”, which had been launched on two contentious grounds. The first was that the trial judge, John Walters, had been mentally unfit to handle the case. The second was that Justice Walters had maintained an inappropriate relationship with the wife’s barrister, Gillian Anderson, while he presided over the dispute.

Anderson revealed that she and Walters had met for drinks or coffee about four times, spoken on the phone about five times and exchanged “numerous” text messages in the 23-month period the proceedings had been afoot.

Anderson, whose husband was killed in a bicycle accident at Cottesloe in 2013, said she had known Walters socially and professionally for years. However, she told Charisteas’s legal team — who had confronted her about gossip from “at least five practitioners” — that she and Walters had never been involved in an intimate relationship, and their “communications did not concern the substance” of the case. Sutherland told those gathered in the Perth courtroom that Friday morning that Walters was a professional colleague, someone she had worked with closely over a long period of time — as was Anderson.

“I’m just simply not satisfied that a fair-minded observer could conclude that I can bring an impartial and unprejudiced mind to the resolution of these matters,” she said. Instead, she would ask that judges from outside WA hear the appeal. The appeal decision would take another two years to land. When it did, last month, it set legal tongues wagging almost immediately about whether the court had made the right decision.

The case has added to the clamour for an independent oversight body to address allegations against the federal judiciary which range from misbehaviour to incompetence. Those calls have intensified following the scandal that engulfed former High Court judge Dyson Heydon, who was alleged to have sexually harassed a number of young female associates. As reported in The Australian last month, the full Family Court of Australia split over whether the close contact between Walters and Anderson justified a retrial.

Chief Justice Will Alstergren’s ruling on the matter was clear — the contact should never have occurred. It was “protracted, premeditated and contrary to the ethical obligations each individual owed to the Court” — and might cause a reasonable apprehension the judge “might not bring an impartial and unprejudiced mind” to the case. This meant a retrial was needed. Alstergren said it was incumbent on judges and barristers to disclose contact that could cause concern — but no timely disclosures were made in this case.

But the Melbourne-based chief was in dissent. The two other appeal judges — Steven Strickland (from Adelaide) and Judy Ryan (from Sydney) said the behaviour would not have caused a reasonable person to fear the judge might have been biased. They said it was their “sincere hope” the judgment would signal the end of the protracted legal dispute.

All hail the chief

Alstergren’s appointment as Chief Justice in 2018 was met with outrage from the sector, because although he had a strong commercial background he had limited family law experience.

However, family lawyers across Australia have overwhelmingly backed his call in the Charisteas case.

It is understood several lawyers have offered to represent the husband pro bono in an appeal to the High Court, so confident are they that the majority judges got it wrong. If such an appeal were successful, it would likely result in a fourth hearing of the complex financial dispute.

The case, launched in 2006, had already had a tortured path when it landed before Walters in March 2016 after two successful appeals. To date, there have been at least 21 judgments.

Even before the full extent of the friendship between Walters and Anderson had emerged, the husband had asked the judge to stand aside because of perceived bias.

Charisteas claimed that during the trial Walters was observed to be “erratic, irascible, interventionist, rude and demeaning” towards the husband’s legal team. The transcript reveals that on one occasion Walters apologised for his “impatience, fractiousness and intemperate comments” the previous day. In another exchange, he reprimanded a barrister for his “smirk”. However, Walters had refused to step aside.

The court of Walters

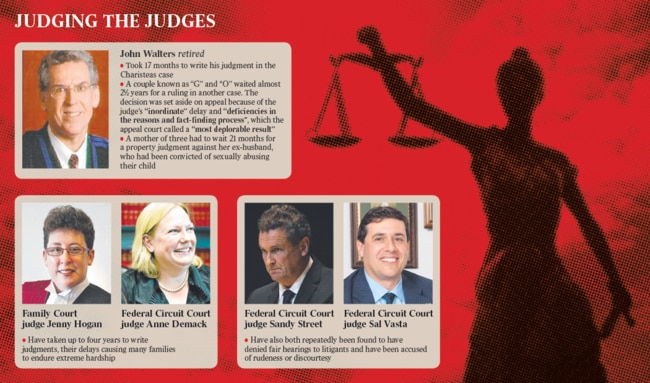

It took Walters 17 months to write his judgment, which was mostly unfavourable to the husband. At some point during the proceedings, the judge applied for early access to his pension. This was on the ground that he was incapable of continuing his role due to permanent disability or infirmity, understood to be mental illness. He retired on February 15, 2018 — just three days after delivering the Charisteas decision.

However, Charisteas was effectively blocked from appealing on the ground that the judge had been incapable of fulfilling his judicial role. Superior-level judges were “immune from civil suit” and disclosing the records would render judgments “open to collateral attacks based not on legal or factual errors but on allegations as to a judge’s fitness”, Strickland said. The Charisteases were not the only litigants to have suffered long delays in Walters’ court.

In one case, a couple known as “G” and “O” were forced to wait almost 2½ years for a ruling. Walters had thrown out G’s property claim on the ground the pair had not been in a de facto relationship for at least two years. But that was set aside on appeal because of the judge’s “inordinate” delay and “deficiencies in the reasons and fact-finding process”, which the appeal court acknowledged was a “most deplorable result”.

In another case, a mother-of-three had to wait 21 months for a property judgment against her ex-husband, who had been convicted of sexually abusing their child.

In yet another case, an appeal was allowed after Walters was found to have drawn negative inferences that were “unfair and unreasonable” and had “acted on evidence inconsistent with the facts”. Charisteas has described the devastating personal toll that the delays have had on both himself and his ex-wife. He suffers from depression and has been placed on medication. After the long wait for Walters’ decision, the appeal judges then took 16 months to deliver their ruling last month. This is despite a goal that 75 per cent of all Family Court judgments are delivered within three months.

Who judges the judges?

Charisteas says there should be an independent body to receive complaints about judicial conduct. At the moment, there is no judicial commission that can investigate alleged misconduct or incapacity at the federal level or in WA (Family Court of WA judges hold commissions as both federal and state judges), although such bodies exist in NSW, Victoria, South Australia, the ACT and now the Northern Territory.

He says he fired off letters to every politician he could think of to raise concerns about Walters’ handling of his case, but all of them fobbed him off. “It’s in the public interest to know whether they are fit to carry out their role,” he says.

“What happens if a judge has a mental issue and they’re unfit to carry on? There’s no continuing review of their performance or capabilities. ”

Walters had joined the Family Court of WA from Melbourne, where he had been a federal magistrate. He had gained a reputation there for being overly harsh on occasion to the barristers who appeared before him but for getting the law right.

University of Queensland law dean Patrick Parkinson says the role of a judge can be extremely lonely. For those who don’t have the support of a partner, family or close friends outside the law, the need to cut themselves off from legal colleagues who appear before them can be especially difficult. “They get where they do, some of them, because they are workaholics. They spend day and night in the law, but if they don’t have a support network the family jurisdiction can be crushing. The work is often so difficult and emotionally wrenching,” he says.

He says chief justices currently “find themselves terribly limited in what they can do” to manage judges who are struggling.

“They can take them off the bench, and give them more time to write judgments but then what happens is they’re sitting alone in chambers … with these long and difficult judgments,” he says.

He believes chief justices need powers at their disposal to help ease judges who cannot cope off the bench. For example, he says, it might be helpful if the chief could offer a judge six months’ pay to help set themselves back up at the bar or in an area of legal practice that better suited them.

Walters is not the only judge who has attracted scrutiny in recent times. The explosive allegations recently levelled at Dyson Heydon made it clear how difficult it was for young women to report complaints when there was no independent body to receive them.

Other judges have been criticised for their performance.

Family Court judge Jenny Hogan and Federal Circuit Court judge Anne Demack have both taken up to four years to write judgments — their delays causing many families to endure extreme hardship. Federal Circuit Court judges Sandy Street and Sal Vasta have also both repeatedly been found to have denied fair hearings to litigants and have been accused of rudeness or discourtesy.

Judicial oversight

The calls for a body that could handle complaints about federal judges have been growing louder.

The Judicial Conference of Australia, which represents the nation’s judges, the Law Council of Australia, which represents the lawyers, and Labor have all been calling for a federal judicial commission to bolster public confidence in the judiciary for at least two years.

Under the Constitution, judges can only be removed from office by parliament for proven misbehaviour or incapacity. The last judge to be removed was in Queensland, more than 30 years ago. University of NSW academic Gabrielle Appleby says in recent years there have been “a number of serious transgressions” or allegations related to federal judicial officers. However, the current methods for holding them accountable, including through the appeals process, “often prove inadequate for the individuals that might be affected by the conduct, for the public’s expectations and for the judges themselves,” she says. “The current system leaves the head of jurisdiction, that is, the Chief Justice or Chief Judge, to deal with complaints, unless they are serious enough to warrant removal, when they might be referred to and investigated by the parliament,” she says.

“The head of jurisdiction has no standing body with power to investigate allegations, and has very limited administrative powers to provide redress.”

Appleby believes that Australia lags far behind comparable jurisdictions, including Britain, many US states and Canada, where complaints-handling bodies have a range of powers at their disposal. This includes a power to send judges for counselling, training or mentoring, to publicly reprimand a judge or make orders for compensation, as well as to refer them to parliament for potential removal or to prosecutors to face possible criminal charges.

She says any federal judicial commission in Australia should have a similar range of powers, pointing out this model was backed by 500 female lawyers in a letter to Attorney-General Christian Porter in July. “While there are concerns that such responses might undermine public confidence in the judiciary, we believe the revelation of misconduct without a mechanism for appropriate redress also poses a high risk of such damage,” their letter said.

Melbourne Law School Associate Professor Alysia Blackham says the focus to date has tended to be on misbehaviour rather than “incapacity”. “We are not dealing with incapacity in a sufficiently nuanced and structured way at the moment,” she says.

“Judges are humans like everyone else. They are going to have issues in their lives, issues of physical and mental health.” She says courts need to proactively manage such issues by putting in place measures to support judges, rather than dealing with it in the ad hoc way they do now. “Often if these issues were addressed 10 years prior they wouldn’t be manifesting in this way,” she says. “There needs to be a better way of managing this, and whatever that way is, it needs to be developed in consultation with the judiciary and it needs to be more structured.”

A path to nowhere

Charisteas, in his 60s, says he now has “nothing left” after working hard all his life. The family and their related companies have spent more than $4 million on legal fees in relation to the dispute.

He says he received nothing from the sale of the house, which he owned before his marriage, his business has been hit by the coronavirus and he is $1.2m in debt.

If the case goes to the High Court and a fourth trial is ordered, the family will be back at square one. A torturous path that will have led nowhere.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout