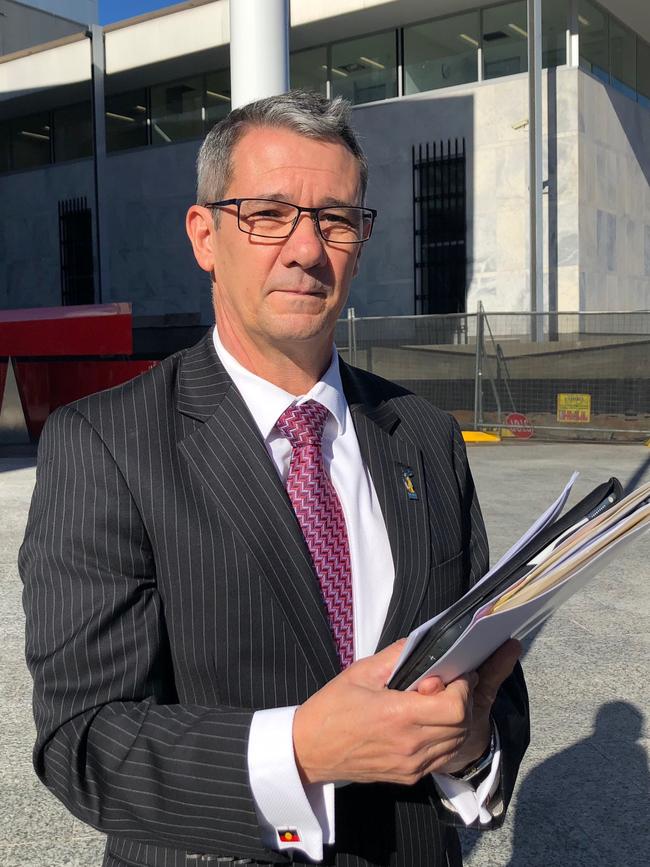

As Director of Public Prosecutions for the ACT, he will decide the fate of the Brittany Higgins affair. It might go to court. But then again, it might come to a sudden end.

Drumgold is duty-bound to ignore the politicians and thousands of others who have made up their minds about this case.

His decision will be based purely on the law, the evidence and the prosecution policy of the ACT.

That policy is outlined in a 46-page document that is about to take on extreme importance. Clause 2.4 says the decision to prosecute involves a two-stage process: “First, does the evidence offer reasonable prospects of conviction? If so, is it in the public interest to proceed with a prosecution?”

But it also makes the point that this does not fetter Drumgold’s discretion: “Where the law or policy ends, discretion begins.”

Higgins, a former Liberal Party staffer, has become a dominant figure in the affairs of the nation ever since she said she was raped by a work colleague in the Parliament House office of former defence minister Linda Reynolds.

The political fallout has been immense and now the legal fallout is about to begin.

The Higgins accusations triggered four separate inquiries by government officials. But a fifth inquiry – by the Australian Federal Police – is the one that counts.

AFP Commissioner Reece Kershaw told a Senate estimates hearing this week that the police investigation was in its final stages and a brief of evidence would be sent to the DPP within weeks.

This is when things will get serious.

If that brief of evidence is inadequate, Drumgold is required to drop this case like a stone. That would be a shattering blow to Higgins and her supporters.

But it would show, yet again, that policymakers can tie themselves in knots unless they recognise that the justice system – and not politicians – have the exclusive right to decide whether criminal conduct has taken place.

If this case never makes it to court, there might still be a case for examining the “culture” of Parliament House and the way women are treated.

There might also be a case for creating a new workplace complaints agency.

But there will be a much greater case for politicians to examine their conduct in this affair in the light of two fundamental doctrines: the presumption of innocence and the separation of powers.

Politicians might not have convicted a man of rape, but they have sent a clear message to the community: Higgins is a rape victim and should be believed. That will look odd if the courts disagree.

If Drumgold is persuaded by the AFP’s brief of evidence and a rape charge does go to court, the politicians need to ask themselves how this man could ever receive a fair trial.

Instead of standing back and allowing the justice system to do its work, politicians have been sending a clear message to potential jurors: they believe this young woman’s account of what happened.

Politicians, not judges, have already decided that Higgins was raped.

That means there is a risk that some of those in the ACT might have adopted the view of politicians they trust. And that means there is a risk that some potential jurors have already made up their minds.

So if this case comes before a jury, nobody could be confident that the jury will reach a decision based only on what they hear in court. That will satisfy nobody – especially Higgins.

If it is assumed, for the sake of the argument, that a rape did in fact take place, Higgins deserves to know that any conviction will be beyond reproach. The accused man has an equally valid interest in ensuring any trial is fair.

The answer is to have this case decided by a judge alone. But unless the ACT parliament changes the law, that might be extremely difficult.

Last year, the ACT parliament made allowance for the impact of the pandemic by temporarily changing the Supreme Court Act to enable those accused of certain criminal offences – including sex offences – to elect to have the proceedings decided by a judge alone, without the benefit of a jury.

But that change, which is outlined in section 68B of the Supreme Court Act (ACT), expires on June 30, which means it is unlikely to be available if the Higgins case goes to court.

A jury trial has long been considered a fundamental right. But Andrew Fraser of the Canberra office of Armstrong Legal has written that suspicions that not all jurors can bring a cold, clinical and dispassionate mindset to court are often behind the election for a judge-alone trial – when that option is available.

In NSW, massive adverse publicity is enough to justify a judge-alone trial.

This is clear from what happened in 2019 when former politicians Eddie Obeid and Ian Macdonald were about to face trial after years of being referred to as “corrupt” and “disgraced”.

The NSW Supreme Court’s Justice Elizabeth Fullerton ordered a judge-alone trial and said: “I do not apprehend that there is any diminution in public confidence, or any shift in the expectation of the community that criminal justice will be delivered, where either the parties agree that a trial should be conducted without a jury … or, where there is no agreement, a judge is satisfied that it is in the interests of justice that a judge-alone trial be convened.”

If this case ends with a just outcome, it will be despite the efforts of politicians.

Chris Merritt is vice-president of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia.

Shane Drumgold SC might not be a household name. But he soon will be.