Mind Medicine Australia founders Tania de Jong and Peter Hunt on what drives them to continue

Famed investment banker Peter Hunt and trail-blazing soprano Tania de Jong’s controversial mission to legalise psychedelics has both brought them closer and been their biggest challenge.

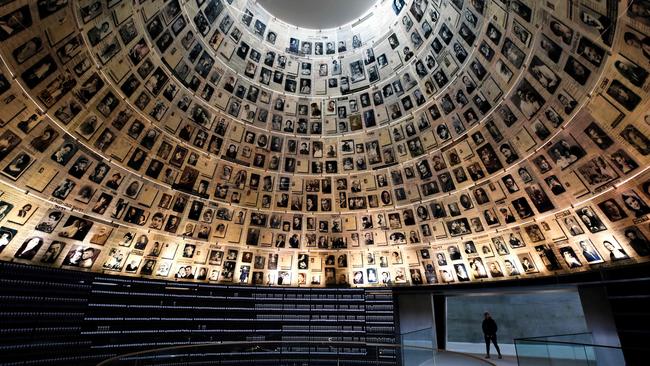

There are few more profoundly powerful and moving places in the world than the vast Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in the ancient city of Jerusalem, the capital of Israel.

On a warm mid-spring afternoon there in April 2012, Melbourne entrepreneur and philanthropist Tania de Jong could not stop crying.

On her first visit to the Holy Land, de Jong was part of an Australia-Israel Chamber of Commerce delegation standing in silence at the famed Path of Remembrance and Reflection.

It was endowed by Melbourne entrepreneur Alan Schwartz’s parents in memory of his grandfather, who perished in the horrors of Auschwitz.

For de Jong that day, as the daughter and granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, the pain was personal. Many in her extended family were wiped out in the Nazi’s dreaded reign of terror. “I had never really been able to read or watch anything about the Holocaust, so going to Israel and then going to that memorial, it was really confronting for me,” she says.

Also on the mission was famed investment banker Peter Hunt, who over 37 years had stints at Macquarie, Bankers Trust and ABN Amro before being co-founder of Caliburn Partnership.

Having lost his father to suicide in his early teens, Hunt was also interested in dealing with past traumas and after meeting her for the first time, instantly found a connection with de Jong. They were married five years later.

Together they have founded six charities supporting causes such as women’s shelters, social inclusion choirs, poverty alleviation and micro-finance. But the most radical, and controversial, is Mind Medicine Australia. The group advocates for the use of naturally occurring psychedelics such as psilocybin from magic mushrooms as therapeutic tools in the treatment of mental illness.

Their psychedelic journey together began on a trip to the Netherlands several years ago, where they ingested a large legal dose of psychedelic drugs through a private therapist. They haven’t looked back.

“There is an enormous bond between us because neither has to persuade the other to start charities or help charities or whatever we do. It’s just natural for both of us,” Hunt says.

“I think that comes out of that experience that Tanya had growing up trying to understand what happened to her family and what happened to me. It is that sort of gratitude that actually, it could have been so bad for us, but it isn’t.”

Family Trauma

Hunt was 13 and living in what he thought was a secure family in a country town in England when his father took his own life.

His father’s business at the time was failing and headed for bankruptcy. He left a suicide note for his wife declaring that taking his life was for the best. Instead it did his family life-long damage.

Hunt’s mother was determined to move on, so emigrated with her family to Australia.

It proved to be a blessing for her son, allowing him to be educated at a good school, university and then to secure a job as a lawyer at a top law firm before moving into investment banking.

Hunt co-founded Caliburn in 1999 and 11 years later the success of the firm was confirmed when US investment bank Greenhill & Co acquired it in a deal reportedly worth around $200 million.

But Hunt has long believed that his hard work, his constant need to achieve and the financial rewards were all a way of escaping from his teenage years trauma.

“I think one of the things that people don’t realise is that when you have somebody close to you commit suicide, you never escape your pain. You’ve got to reach out to that pain and accept it rather than trying to smother it,” he says.

He believes the self-made, “protective” barriers he maintained for decades have fallen away significantly since his first psychedelic experience.

“What the medicines did was actually connect my brain. You come out of the experience feeling incredibly connected. I’m now much more thoughtful about life and what it is. I’m much more contented with myself,” he says.

“I am now more philosophical about the pain. My father’s suicide happened but now I can see the good sides of it, not just the bad. It just released me when I came to Australia and I had massive opportunities I would not have otherwise had.”

Hunt was married young and became a father when he was just 21. He held the eldest of his two daughters in his arms at his university graduation.

They are now in their 40s, while he also has a 13 year old granddaughter. De Jong says they can see how their father has changed as a result of his treatment.

“He’s so much more communicative and more heart centred,” she-says, adding that she was initially drawn to their relationship by Hunt’s creative and deep thinking as well as his ability for “brilliant analysis”.

But Hunt adds an important caveat, indicative of how much time he and de Jong spend on MMA work.

Smell the roses

“My daughters love what we are doing. But for both of them the most precious thing is time. For them, MMA is taking up too much time for me. I am not spending enough time with my kids and granddaughter, and somehow we have to rationalise what we are doing with MMA,” he says.

De Jong was not fully aware of her family’s experiences in the Holocaust till she was aged 12. When she found out, she gave up her Jewish religion, which upset her mother Eva enormously.

Eva, who is now 84, released a book titled “Driftwood” telling the amazing story of her grandparent’s escape from the Nazis.

But de Jong believes her treatment with psychedelic medicines helped her come to terms with her past, as well as her break-up in 2010 with her long term partner - famed baritone Jonathan Morton - plus the passing of her beloved father three years ago.

“I miss my dad every day but it is just one of those sad facts of life. I think the medicine helps you come to terms better with death,” she says.

De Jong - a soprano singer - and Morton still tour the world performing together and she now feels a better ability to “appreciate the beauty of life a lot more.”

“A lot of people used to say to me, ‘don’t forget to smell the roses’ and now I actually really do smell the roses,” she says.

“It is that sense of grounded-ness, being part of something and being content with yourself.”

Hunt describes his wife as now “less rigid” and not as egotistical as a result of her treatment.

“She’s always been very caring. But I think she’s also been very driven and very ambitious. Now I think the ambition has come down, but the drive is still there,” he says.

“She’s a soprano singer, she’s a big thing. But actually, the ego has really come down. It is the same with me as well. I think that’s part and parcel of the experience with the medicines.”

Psychedelic-assisted therapy (PT) is growing in popularity across the world following endorsement by studies from respected institutions such as Imperial College London and Johns Hopkins University in America claiming that the treatment, properly conducted by professionals, can help with intractable depression.

Imperial College’s Head of Neuropsychopharmacology, Professor David Nutt, has been touring Australia in recent weeks with the support of MMA to speak on the subject of psychedelic-assisted therapy.

Yet while there is growing support for PT having a place in treating patients with long-standing depression, one of its key challenges is the requirement for trained staff to undertake intense in-patient observations for effects and side effects during treatment.

Its critics have also warned about dependence or addiction to the drugs, causing it follow to same path as, for example, Oxycontin.

New frontiers

Use of the drugs by psychiatrists remains illegal in Australia and MMA has just made another submission to the Therapeutic Goods Administration requesting that psychedelic medicines be rescheduled in the Poisons Standard, on a highly restrictive and supervised basis.

There are currently five clinical trials of PT being conducted nationally, including one at St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne to treat end-of-life depression and another at Monash University.

In March last year, the Australian Government also committed $15m to psychedelic research.

Private investors, including billionaire Andrew Forrest, are moving into the space.

In August his Tattarang Group launched a $250 million venture capital fund called Tenmile for healthcare investments focussed on new therapeutic areas, including the use of psychedelics.

Tattarang has since invested in a firm called Emyria, which is working on a psychedelic-assisted treatment for post-traumatic stress.

In October an Australian firm called Psylo, backed by the CSIRO’s Main Sequence Ventures, raised $5 million to develop new therapies to treat mental illness modelled on naturally occurring psychedelics.

In August the Hunt Family Foundation committed $1m to PT trials and Hunt says he is now confident of receiving $5m from other philanthropists to back various observational trials, starting with one for emergency service workers.

“The beauty of observational trials over clinical is you are taking in real life people, rather than people who just fit into a box,” he says.

Responding to critism

MMA was rocked in September by a Four Corners investigation criticising its workplace culture and alleging it had associations with underground therapists and high staff turnover.

MMA quickly rejected the key allegations and Hunt now claims the program “brought out massive support for us.”

MMA also attracted media criticism when it applied to the Federal Court in August to unmask several anonymous Twitter accounts criticising the group.

Hunt now justifies the action because “they were constantly personally attacking Tanya” but reveals MMA decided two months ago to withdraw it.

“Frankly, the people who were doing it, we know who they are. They are traumatised people. So you can think of them as really nasty people, or you can try and be compassionate,” he says.

De Jong also rejects allegations of MMA’s alleged history of litigiousness. Four Corners claimed it harassed a former employee and threatened another with bankruptcy.

“We’ve sent just two lawyers letters to people who we did know the identity of who were defaming us. They subsequently apologised and they also signed agreements not to continue,” she claims.

The MMA board, which includes Hunt, de Jong and big names such as Andrew Robb and Simon Longstaff, has also been pushing to install an independent, professional chief executive for the group, which is yet to happen.

Psychedelic therapy is clearly an evolving and challenging field. Given the history, de Jong acknowledges it will continue to carry a stigma. But so-be-it.

“The way we see it is the closer it gets to getting these medicines registered, the bigger the backlash will be. Where a fundamental shift is occurring, there will be people pushing against it,” she says.

“We need to come to terms with the fact that we are pioneers. We will be attacked and we need to get used to that. We prefer to think of the finishing line. That is about more people getting well.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout