Military managers: Why this CEO hires ex-military personnel and urges businesses to follow his lead

Half of his senior team is ex-Australian Defence Force but Aspen Medical chief, and former soldier, Bruce Armstrong says the value of military leadership skills is unappreciated in business.

Mosul was Iraq’s second largest city – the oil-rich political, economic and cultural centre of Nineveh province when Islamic State militants overran its people in June 2014.

Three years later, Iraqi security forces launched a major offensive to retake the city with the support of Kurdish fighters, Shia paramilitary forces, Sunni tribesmen and American-led coalition air strikes.

Bruce Armstrong will never forget the apocalyptic scenes when he landed there in 2017 after the firm he now runs, Aspen Medical, was contracted by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to provide healthcare professionals and hospital management at a 48-bed facility south of the city.

“I can still see clearly the picture of one of our Kurdish security bringing in a poor young boy who had suffered blast injuries. He was our very first patient,” Armstrong recalls shaking his head before a poignant pause.

“I was there only for a short amount of time but being heavily involved in the project management, I felt a deep sense of a duty of care for our people who were there, given the horrific stories and scenes they encountered of what human beings can do to each other.”

Aspen Medical now has thousands of staff around the world whose mission is to save lives in war zones, countries hit by deadly pandemics, and other challenging situations.

Over the past 20 years, Aspen has provided healthcare solutions to governments, defence forces and humanitarian organisations in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the UK and the US.

Before joining the company, Armstrong had a proud history of military service in Australia and the UK.

In fact half of Aspen’s management team is ex-Australian Defence Force, including its charismatic founder, Glenn Keys, who worked as a flight test engineer after graduating from the Royal Military College Duntroon in Canberra and spent 15 years in the army.

Keys later worked for a defence start-up and then defence contractor Raytheon before co-founding Aspen in 2003. The Canberra-based company’s first contract was to deliver a plan to reduce elective surgery waiting lists for the National Health Service in the UK.

Armstrong believes the value of military leadership skills is unappreciated in business and urges more companies to follow the lead of Aspen by seeking out ex-ADF employees – especially given the nation’s proud Anzac heritage and the values established in the crucible of war.

“The amount of time where there is authoritarian control is very minimal when you are in the defence force,” he says.

“For me, more often than not it was about commanders saying, ‘This is my intent. You go away and work up your plan and then I’d like a back brief’.’ It was never about ‘Do this exactly like this’, or directive control.

“I think it is a widespread misconception, in particular here in Australia, that everyone in the army gives and takes orders. That is far from the truth.

“Rather I think that veterans are very well equipped to work in an ambiguous environment and to handle matrix management.”

This also extends to actively encouraging more veterans to move into roles in business as part of their transition to non-military life.

Aspen has established its own veteran professional network that is open to ex-ADF members and their families.

This includes running forums where ADF veterans working in Aspen’s senior ranks speak to network members about their experiences transitioning out of the military into business.

“They leave the ADF as a person. A person who responds extremely well to training, who has a very strong work ethic, who is a great team member,” Armstrong says.

“I think if employers understood all the attributes, then they might lean in more to hiring veterans. Because they are going to get a great win out of it.”

Destined for military service

Armstrong grew up in a military family in Sydney.

His grandfather was in the Royal Navy, and his father served in the Royal Australian Navy.

Due to the length of the tours abroad, the latter didn’t actually see his son in the flesh for the first time until he was three months old.

Armstrong junior was 21 when his father suggested he follow in the family tradition.

“Then, sure enough, someone appeared at my door to say, ‘Yes, we’d like to talk to you son’,” he says.

“But I went to Portsea, not Duntroon, because Portsea was where they sent people who had their degree and soldiers who were more mature aged. As I called it, men’s school.”

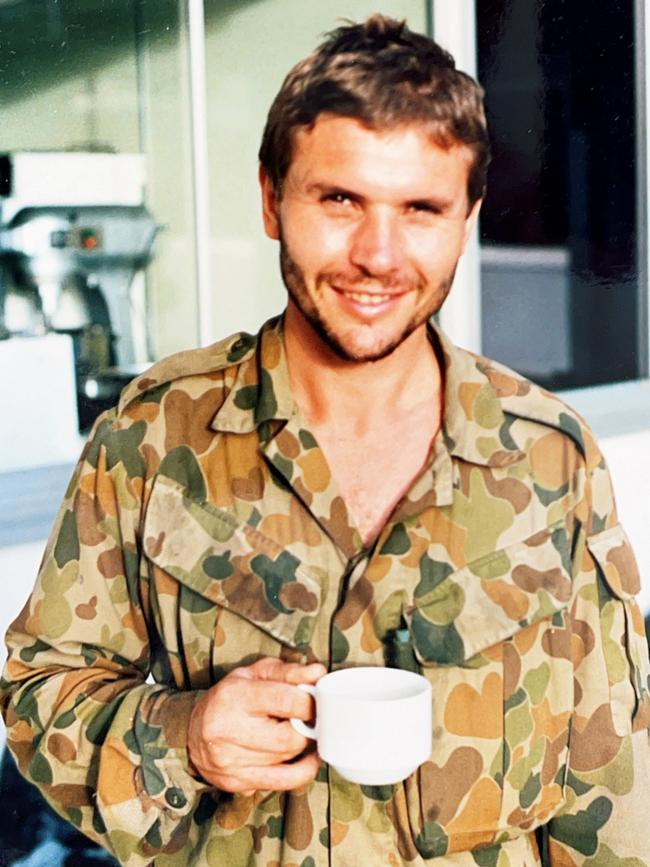

He graduated to the artillery division of the army and spent one quarter of his military career there. Another 50 per cent was in operational jobs, including a period in 1987 in a sabre squadron – or sub-battalion-sized operational unit – within the elite Special Air Service Regiment (SASR) in Perth.

“That was the highest level of professionalism that I’ve ever encountered. An incredibly committed, professional, brave collection of men served in that unit and serve today and every Australian should be very, very proud of the work that they do,” he says.

“You had to prove yourself every single day in the regiment and that was the standard that was expected of everyone.”

In September the federal government revealed that a small number of military commanders had been stripped of their medals after the so-called Brereton report that found Australian troops were involved in the alleged unlawful killing of 39 people in Afghanistan.

The Special Air Service second squadron was disbanded in the wake of the report.

Armstrong will not comment on the findings, except to say that the accused soldiers fundamentally deserve the right to explain their actions.

“If those actions have been unlawful, then people have got to be held to account and it’s as simple as that,” he says.

“But until any criminal allegations are tested and proven in law, all parties deserve the presumption of innocence, and later, if required, given the chance to defend themselves in a relevant court of law.”

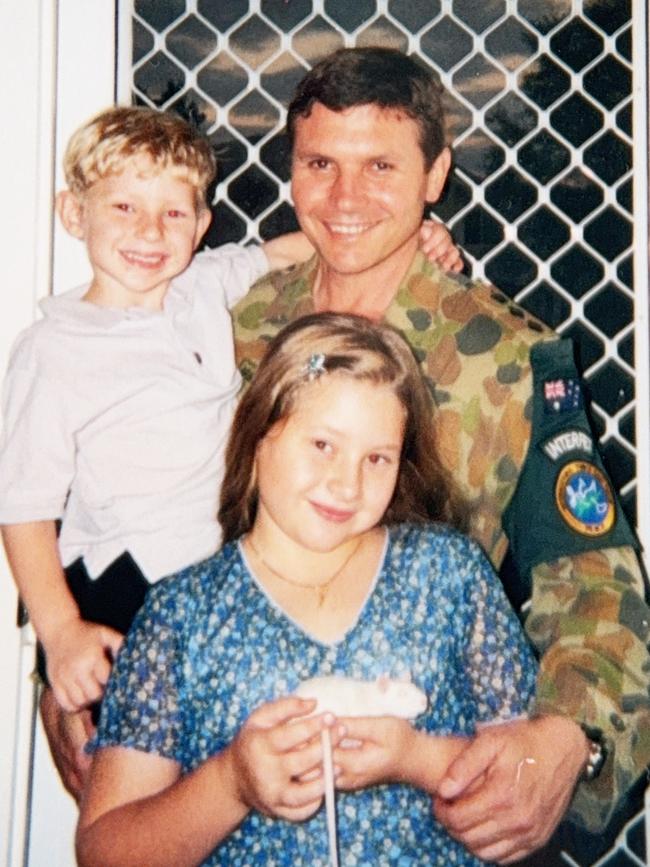

Armstrong also had four years in the intelligence service on “special projects” before his final appointment – a highlight of his career – as then General Peter Cosgrove’s chief of staff in East Timor during the Interfet deployment.

After leaving the ADF Armstrong held a variety of senior executive-level roles in business, including in a global enterprise software company, a private equity-owned national building service company, and a publicly listed company in the automotive industry then called Allomak Group and now known as AMA Group.

He first came across Aspen when he was introduced to Glenn Keys by a mentor.

“I talked to Glenn and he’s just such an impressive person in terms of his passion for the company, and through his and his wife Mel’s absolute commitment to social purpose,” he says.

After taking the initial role as Aspen’s chief operating officer in 2012, Armstrong will never forget an episode which occurred while he was on his way to a management meeting at the company’s headquarters in the Canberra suburb of Deakin.

Over the frantic minutes that followed, he literally saw two Aspen staff save a man’s life.

A contractor who was visiting the building suffered a heart attack and was kept alive by two of Aspen’s paramedics who, coincidentally, were visiting at the time.

“The last time I saw that level of professionalism was when I was in the defence force. But it was people not trying to save a life, they were trying to take one,” he says.

“I remember that day thinking, ‘How good is this job? I knew we were going well commercially, but the basis of what we do is we literally improve people’s lives and that episode just highlighted that we save lives every single day. I just felt this is fantastic. I’ve never looked back.”

Armstrong was appointed group chief executive of Aspen in 2014 after serving as chief of staff and then COO for two years.

From January 2025 he will also take over as an executive director on the firm’s global board.

Over two decades Aspen’s workplace has been consistently ranked ahead of the industry average in many categories, including equality, belonging, wellbeing, flexibility and choice.

Armstrong describes the culture as inclusive and supportive.

“I’ve lost count of the amount of times people new to the company have come up to me and said ‘I can’t believe how welcoming people are in this company’,” he says.

“It speaks to a culture that goes right down through the organisation.”

Giving back to the community

Armstrong says his biggest lesson from Glenn Keys and his wife has been to give back to the communities you live in.

The Keys first got interested in supporting services for people with disabilities when their second child, Ehren, was born with Down syndrome.

They have since established the Aspen Medical Foundation, which receives a percentage of Aspen’s profits and partners with charities and corporations to address underfunded health issues.

The Keys have also launched Project Independence, a social enterprise which helps people who have an intellectual disability purchase their own home.

Glenn Keys was named ACT Australian of the Year in 2015, and received an Order of Australia in 2017 for philanthropic leadership and advocating for people with an intellectual disability.

In August 2023 Ehren celebrated 10 years of working with Aspen, after starting his journey as part of the firm’s corporate support team.

He then moved to payroll and is currently working in the culture and performance division.

One of Ehren’s most memorable moments with Aspen was when he was supported to speak at an event to celebrate World Down Syndrome Day last year.

“He is just an absolute joy to have in the company. He’s got such a positive attitude, which is totally infectious. He’s so good for our company culture. We get back much more by employing him,” Armstrong says.

“We have other disabled people who are employed here as well and it’s the same with them. But Ehren in particular has such a really huge personality and invariably he makes you smile every single day.”

Going forward Armstrong says Aspen wants to build on its roots to continue to export the best healthcare solutions around the world.

Two years ago it joined with the Alcoa Foundation to deliver medical training and prosthetics supplies into war-torn Ukraine and that work continues to this day.

It wants to be part of more important national projects across Southeast Asia, the Pacific, the Middle East, North Africa and the Americas.

More recently Aspen announced a new strategic vision to staff which is a solution to every healthcare challenge globally, supported by three strategic goals: service excellence, social impact and sustainable growth.

“We are proud of our Australian heritage because a lot of the foundation of what we export around the world comes from here,” Armstrong says.

“It is more than knowledge capital and more than intellectual property. It is Australian compassion that we export from this country. That won’t ever change. Because at the end of the day, we are Australian, we are veteran owned, and we are proud of it.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout