How the Myer family and NASA have influenced this scientist’s passion for a dementia cure

South African born, Melbourne educated Professor Peter van Wijngaarden heads the largest brain research centre in the southern hemisphere and the marathon runner’s cause is personal.

The charming town of Fish Hoek boasts a picturesque beach in the shadow of mountains, a short drive from the bustling metropolis of Cape Town on South Africa’s Western Cape.

It is the birthplace of a medical professor named Peter van Wijngaarden, the now chief executive of Australia’s Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health – the largest brain research centre in the Southern Hemisphere.

Van Wijngaarden has few memories of the economic and political turmoil that rocked South Africa during his early years. Before he had started in kindergarten, his family had fled Fish Hoek to start a new life in Australia.

There, in suburban Melbourne, an event happened which would change his life and forge his passion for medicine.

In 1981 when he was five years old his mother, Marijcke, suffered a stroke during what was supposed to be a routine medical procedure at the Austin Hospital in Heidelberg.

She survived the brain haemorrhage but had a long recovery and had to learn to walk and talk again.

“So she was one of the first people in Australia to have a metal clip put on the aneurysm at the back of the neck that allowed her to survive,” her son says.

The stress of her uncertain and prolonged recovery led him to develop obsessive compulsive behaviours, such as routinely lining up his clothes in the wardrobe and checking the doors were locked at the family home in Wheelers Hill.

He feared that if he didn’t, his mother would not come home.

“It’s the nature of what is called an obsession. You know that you have this compulsion to do something that’s not connected with an outcome. Because in your mind, it is somehow linked to something bad happening,” he says.

“It is behaviour that we see in people with obsessive, compulsive disorders. I’ve never had that again in my life. I think it was just the enormity of that situation that overwhelmed me.”

Tragically his mother, who is now 76, has since suffered from chronic pain, headaches and developed a serious form of cancer known as lymphoma.

At the age of 51 and 27 years ago van Wijngaarden’s father, Pieter, retired from work to care for her after the family moved to Tasmania.

The trauma of his mother’s illness has been a constant thread through van Wijngaarden’s life and those of his older sister and younger brother, and one of the key reasons he took up medicine.

Before coming to The Florey, van Wijngaarden – an ophthalmologist and medical scientist with research interests in retinal imaging biomarker discovery, artificial intelligence, oligodendrocyte biology and angiogenesis – was deputy director of the Centre for Eye Research Australia.

There he led a team of researchers with expertise in mathematics, engineering, data science, clinical ophthalmology, and astrophysics that applied hyperspectral imaging to the eye.

The group discovered imaging biomarkers for a number of diseases, including Alzheimer’s, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy.

The discoveries have served as the basis of two patent applications for the first-in-human findings identifying a retinal biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease.

At the age of 48, van Wijngaarden is younger than most of his peers running medical research institutes in Australia. But his passion for the job is deeply personal.

“Part of that comes back to the motivation with my mum seeing the huge impact that brain diseases have on individuals and families,” he says.

“I really see it as the final frontier of scientific knowledge in the human body. We know tremendous amounts about cancer and cardiovascular disease but the brain, for me, is this big frontier of discovery.

“I think we are really on the cusp of a revolutionary stage of neuroscience research. Diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, which have not been treatable up until 2023, are now treatable.

“There is a whole new wave of innovation following. So to be part of that, at this time, is so exciting.”

Myer patriarch’s enduring influence

After attending a Uniting Church school in Melbourne, van Wijngaarden studied medicine at Monash University.

During his third year of study in 1996, his father secured special permission to sit in on his son’s neuroscience lectures as he desperately sought solutions for his wife’s mental health challenges.

After graduating, van Wijngaarden Jr moved to St Vincent’s Hospital for his residency, then decided to do research, initially for a year before later pursuing a PhD at Flinders University in Adelaide.

It focused on blood vessel formation in the eye, which was at the forefront of new treatments for eye diseases.

After completing his ophthalmology training, he received an NHMRC scholarship to study regenerative biology of the brain in multiple sclerosis at Cambridge University in the UK.

His postdoctoral fellowship work at Cambridge between 2011 and 2013 led to human clinical trials on multiple sclerosis, and he returned to Australia to start his own research group in 2013.

He then pivoted his research to imaging the eye to detect signs of brain disease, and in 2015 received funding from the Myer family’s prestigious Yulgibar Alzheimer’s Research Program after meeting family patriarch Ballieu “Bails” Myer over dinner.

“Bails was in his late 80s but still did a lot of his decision making around the dinner table, and was always just so hospitable and remarkable, always introducing himself as a humble salesman,” van Wijngaarden recalls.

“But Bails had this very clear vision that we needed to think laterally and ask daring questions to really move the needle on Alzheimer’s disease. Samantha, his daughter was equally committed.

“So we pitched our ideas over dinner, and there was a scientific advisory committee that judged our application as well. Fortunately I was selected as one to share in the $10m provided.”

The money from Yulgibar, which was focused on the Florey, funded the development by van Wijngaarden and his team of a novel imaging technology based on NASA satellite imaging to detect signs of Alzheimer’s disease in the retina.

The work led to the first evidence that a one-second photograph of the eye could detect signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

Van Wijngaarden then co-founded a start-up tech firm called Enlighten Imaging that commercialised novel retinal imaging technology for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

These cameras are now operational at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, the KU Leuven University in Belgium, the Umea University in Sweden and The University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand.

“The fact that I started really looking into Alzheimer’s disease was all due to that visionary support from Bails,” van Wijngaarden says.

Myer died at his home at Merricks on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula on January 22, 2022 – 11 days after his 96th birthday.

“I’m still very close with the family. I’ve been to the family house many times and went to the funeral. I had lunch with Bails and Samantha about a month before he died, in his home,” van Wijngaarden says.

“That’s the extraordinary thing that when you were supported by Bails, you were almost part of the family.”

The Florey has had a strong connection with the Ian Potter Foundation, a major Australian philanthropic foundation established in 1964, while the late Dame Elizabeth Murdoch – the mother of Rupert Murdoch – served on Florey’s ethics committee for many years.

Going forward, van Wijngaarden has a keen interest in continuing to commercialise The Florey’s work to transfer its research to the real world.

But the ongoing challenge is funding.

“Medical research in Australia is, I think, at a really critical point. Particularly independent medical research institutes, they are really on the cusp of viability,” he says.

“Because the cost of research is going up but the amount of support that is provided in terms of grant funding is not really increasing. So there is this growing gap.

“That underscores the criticality of commercialisation. So we have a big program of commercialisation at The Florey, and have a few really exciting things that are likely to transform the sustainability of the organisation and achieve massive clinical impact.”

As a past member of the Australian Alliance for Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Workforce Program Committee, he sees huge value in using artificial intelligence in neuroscience.

The retinal imaging technology he developed for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases already uses AI.

“I absolutely think we are on the cusp of a revolution in the way in which research is done. Increasingly, research is going to be powered by AI. A lot of the stuff that we do in the lab will transition to stuff done computationally in AI code, and that will enhance the commercialisation,” van Wijngaarden says.

“Importantly for patients, accelerating drug discovery and drug development with AI is hugely promising.

“How we position as an institute in that context is a big question we are working through but we need to act now to make sure that we are relevant into the future.”

Running to clear the mind

Van Wijngaarden’s sister, Nicolette, was long known as a glamorous Sydney real estate agent who counted Chris Hemsworth, Paul Hogan, Collette Dinnigan as clients.

But five years ago she and her real estate agency, Unique Estates, were convicted of being behind the biggest real estate fraud in New South Wales history.

She spent 18 months in jail after pleading guilty to pilfering $3.6m from the company’s trust account to keep her business afloat.

Her brother describes the affair as “just an extraordinary challenge to the whole family”.

“It was a very difficult situation. She had a failing business. But I was completely shocked by what happened,” he says.

“Ethics is at the heart of what we do in research and so it was difficult for me, professionally and personally. But it was absolutely devastating to my parents.”

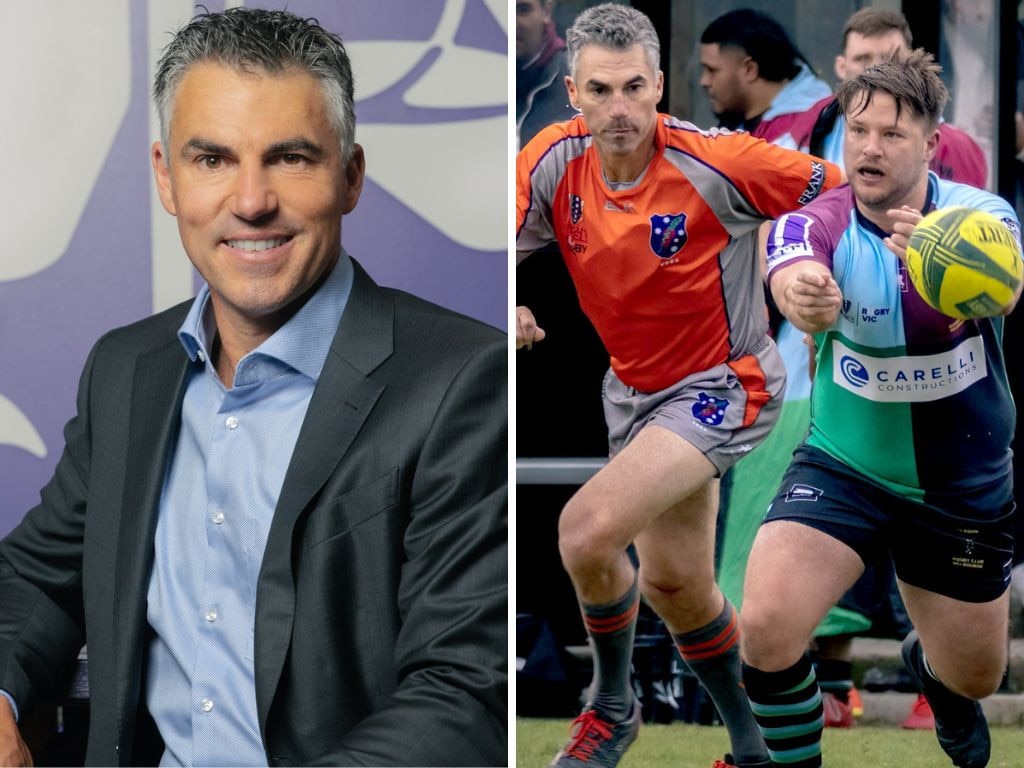

Van Wijngaarden long ago turned to long-distance running as a leisure past time and to manage the many stresses of his family life.

He now regularly runs to his office at Parkville on the northern edge of the Melbourne CBD from his home in beachside Brighton and has represented the Netherlands in ultra-marathons internationally.

He has run an impressive 15th place in the Sydney Marathon and 13th in the Gold Coast Marathon.

Interestingly he describes top-level long distance running as “deeply humbling”.

“It makes you realise that you have your limitations. For me it is also stress relief. It gives me mental clarity,” he says.

“I work through problems, not really consciously, just in the background while I’m running. I often find that at the end of the run, I’ll have a new perspective or have come up with a solution to something that’s been challenging to me.”

He and wife Amber, who he calls a “superhero” and works as a radiologist, married 19 years ago and have two children aged 14 and 12.

Their father is a hands-on dad who juggles making school lunches and the morning school drop-off with his work.

“Our kids have always just kind of accepted that Oma – that’s what they call their grandma – has frequently got pain and often has to take naps,” he says.

“It’s just what they’ve come to know.”

While the prognosis for Marijcke van Wijngaarden is challenging and her problems will continue to be complicated and difficult, her son says his commitment to neuroscience research is not just about trying to fix his mum.

“It is more about ‘how can I help to move the needle for other people affected by neurological diseases?’ That is absolutely my driving motivation,” he says.

“But it is also driven by curiosity, fascination and just a passion for the science.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout