And the colonial-style desire for London control eventually led to the Chinese state-owned enterprise Chinalco becoming Rio Tinto’s largest shareholder.

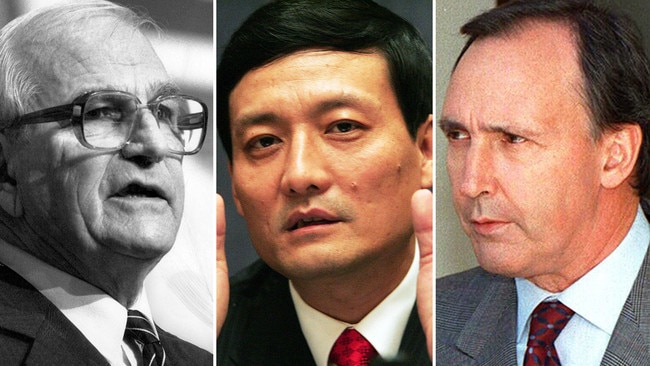

I learned what happened this week after accusing the Prime Minister of the day Paul Keating of making a “mistake” in allowing a dual listed structure combining London’s Rio Tinto and its then Australian controlled affiliate CRA without stipulating the number of Australians that had to be in the combined board and that head office be in Australia. Five years later, as Treasurer Peter Costello insisted these stipulations be in writing when he approved a similar deal between BHP and Billiton.

As you might expect, it wasn’t long before Paul Keating was on the phone to me. And by combining both our experiences we can now fit together the jigsaw. We do not know when the Londoners at Rio Tinto’s plush St James Square offices decided that it was inappropriate for the former convict settlement to control the Australian assets. But some years earlier, Rod Carnegie, as CEO of CRA in Australia, had wanted to make a bid for Rio Tinto. Carnegie was blocked by Rio Tinto’s mates on the CRA board, but a seed was planted.

It started germinating when Robert Wilson became Rio’s CEO in 1991. Wilson patiently waited until Rod Carnegie’s successor, the boy from Broken Hill, John Ralph, had retired as CEO. Then it was then time to move on a dual listed structure which would see two companies, RTZ and CRA, owning the total business with the same boards and management – exactly what now happens with BHP. At the time Shell had a similar structure in the UK and Holland.

Rio/CRA had to gain permission from Paul Keating and then treasurer Ralph Willis. Among their requirements were that there be at least one third of Australian directors, similar to what Peter Costello would later do with BHP. But then a stunning event took place. The chairman of CRA was John Uhrig, a great Australian who was a former CEO of Simpson Pope. He is a legend in Australian corporate history for his role as chairman of Westpac in resisting the push by Kerry Packer and his henchman Al “Chainsaw” Dunlap to control the bank.

Uhrig’s ultimatum

Uhrig – with the support of the other Australians on the CRA board including former Ford Australia CEO boss Bill Dix – met with Keating and Willis. Uhrig stunned Keating and Willis by stating that if they insisted on the requirements about the makeup of the board, the Australian directors would immediately resign and Keating would have to find new Australian directors to satisfy the requirement.

Uhrig’s genuine view (which he discussed with me at the time) was that Australians would gain their posts on the joint board on their merits and didn’t require a government direction. He told Keating that he didn’t want to be a director of a combined company on government orders. I have no doubt that neither Uhrig or Dix had knowledge of the Rio Tinto/ St James Square master plan and indeed assured Keating and Willis that there would be greater Australian control. Keating and Willis did not relish the task of finding Australian directors, and so gave in. And the rest is history.

Uhrig became chairman and for a time Australian influence grew as he promised. But he retired some three years later and was replaced by Londoner Robert Wilson as “ executive chairman”. Australians Leigh Clifford (later Qantas chairman) and Leon Davis initially played key management roles but it was all over. Control had passed to St James Square and the Australian head office over time was disembowelled.

City control

But London’s anti-Australian control culture did not end with the dual listing saga.

Later around 2007 BHP wanted to bid for the combined company and the horror of seeing control pass to Australia prompted the Londoners to buy Alcan for $US38bn — mostly borrowed. That made the company too big for BHP but it was a horrendous mistake and huge losses were incurred by Australian shareholders. Australia had not only lost control but its shareholders were hit hard by the St James Square brigade. BHP bid again for the crippled Rio Tinto but that led to the Londoners at St James Square bringing Chinalco in as “a white knight” so they would retain control. Australia has curbed Chinalco’s holding to 15 per cent and so far has prevented board representation. But as I explained earlier this week, Rio Tinto, Chinalco and Chinese state owned steel maker Baowu are looking to develop Simandou as an alternative supplier to Australia. .

The strategy has the backing of Chinese President Xi Jinping. When the BHP case came before Peter Costello there were only three Australians on the board of 15 Rio directors. Today there are still three but the board number is down to 12. However the chairman, CEO and chief finance officer are all non Australians. Rio Tinto shareholders will be hoping Simandou is not another Alcan. Meanwhile currently in Australia the St James Square brigade is in a dispute over the destruction of sites of great significance to Aboriginal Australians.

The tragic story of how Australia in 1996 was duped by Rio Tinto’s London executives and board into ceding control of the vast Hamersley iron ore deposit and other Australian mineral riches is finally out.