Executives in companies around the world, including AMP, QBE and David Jones, have lost their jobs on revelations of allegations of sexual harassment and poor or inappropriate behaviour.

Late-night drinking in the workplace that led to some of the incidents reported in Canberra would be the subject of instant dismissal of those involved.

In some situations, such as the case of Nine Entertainment’s well respected Hugh Marks, even consensual relationships have led to the departure of the executive.

Business is far from perfect, but on a broad range of issues such as workplace standards and environment, social and governance issues (ESG), Australian business is being increasingly held to global standards that are stricter and more advanced than those set by government in Australia.

Major companies know they are operating in a global world and must adhere to, or try to adhere to, global standards in terms of workplace behaviour, treatment of employees, moving towards lower carbon emissions and more environmental responsibility and in their sourcing of materials and supply chains. Decades ago, it was the government of the day that set minimum standards.

Some companies at least would push out the envelope in the pursuit of profit until they were hit with fines and government action.

Continuous disclosure requirements

But these days the combination of continuous disclosure requirements, and a range of more activist shareholder groups, and an overlay of critical observers such as those rating companies on their ESG standards — fuelled by an instantly enabled digital world — means that listed companies and the foreign arms of global companies at least have to operate to global standards.

When it comes to ESG — particularly on environmental issues — the thoughts of investors and activist groups in Europe and the US are now translating directly into pressures on major Australian companies, pushing them to take positions far ahead of what is required by local law.

For example, a global mining company operating in a Third World country could find itself being held to higher standards by an activist shareholder group or ESG investors or by the government of the country in which they are operating.

Business leaders were surprised when Scott Morrison responded to incidents in Parliament House by referring to his discussion with his wife and his thoughts about his daughters, when being responsible for the standards in a workplace is a normal part of the job for an executive in the private sector.

In an interview this week, Goldman Sachs investment banking executive director Nicole Beavan and head of ESG sales in Australia Brett Zeolla talked about the global shift to awareness by companies of ESG issues that are affecting corporations around the world. They talked about how directors and executives were keen to get briefings on global ESG trends and issues to see how they affected their companies.

Zeolla said 2020 had been a “watershed year” for ESG investors with more than $US270bn flowing into specialist funds around the world, and another $US90bn in the first two months of this year.

Tip of the iceberg

But these are the tip of the iceberg — part of a broader trend by the broad sweep of institutional investors taking up ESG issues with the companies they invest in.

These days capital is global and becoming increasingly socially and environmentally aware — and is prepared to use its muscle, pressing executives on social media or at annual meetings.

There are now more than 3000 fund managers who have signed up to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment, Zeolla said, including 200 in Australia.

These in turn were putting pressure on the companies they invested in to comply with these principles.

Zeolla said there were now as many as 600 different agencies and organisations rating companies on their ESG standards.

These days, some were conducting ESG roadshows with investors to outline what they were doing when it comes to environmental and social issues.

The ESG lens is also being cast across the portfolio of assets held by a company, including those it will sell off and those it will buy.

As Zeolla said, companies that find themselves hit with ESG scandals find their share prices damaged in a way that can often take a long time to recover from.

“If you are not nailing this,” Beavan said, “investors are going to do it for you.”

She said while ESG issues of the past were largely the “e” of environment, there was now much more concentration on the “s” or social part of the equation. This could include the hiring of women and minorities and representation on boards and at senior level.

Companies are under pressure in areas such as their treatment of minorities and there is a new area emerging of companies under pressure to be more cognisant of issues affecting the mental health of their workforce.

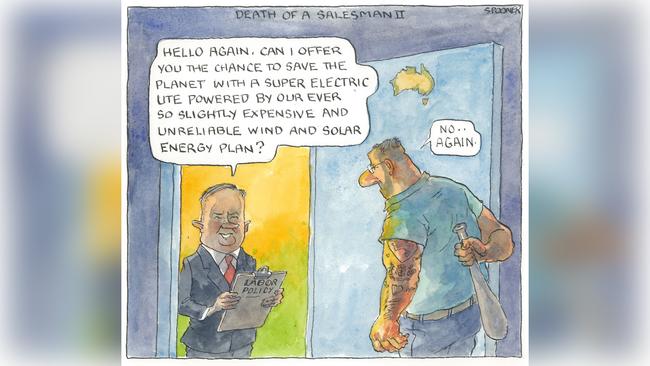

It’s a long way from the incidents in Parliament House but the principle is the same — the corporate sector is being forced to comply with global standards while government is lagging.

Different attitude

The issues in Parliament House highlight a different attitude to the workplace that was what surprised so many people as the embarrassing revelations tumbled out.

The incidents also highlight how the design of a workplace can affect behaviour.

In the original design of Canberra by Walter Burley Griffin and his wife Marion Mahony Griffin, Parliament House was not even meant to be on the top of what was originally Mount Kurrajong.

On the top of the hill was to be a “capitol” building, like the Capitoline Hill in Rome that was to be a public space. Parliament House was meant to be further down, with a continuous flow from the capitol building — a building of the people that would overlook the politicians further down the slope, and on to the lake with federal buildings on either side.

The balance was messed up in the 1920s, when the Hughes government pushed ahead with a temporary parliament closer to the lake. After years of delay, largely due to World War I, there was pressure to move the capital from Melbourne to Canberra as envisaged in the constitution.

The urgency to move saw the construction of a “temporary” Parliament House with ideas for a grander one to come later.

But as Griffin himself warned a parliamentary committee, once a temporary structure was built it would become permanent.

When it came to building the new Parliament House, under the Fraser government, there was a debate over its location.

Instead of locating it on what was then known as Camp Hill, where Griffin wanted, it was decided to locate it on the top of what is now known as Capital Hill.

Two factors shaped how it was built. Italian-born architect Romaldo Giurgola, who designed the building, was a fan of Griffin, having seen his plan for Canberra at the university in Rome where he studied architecture.

Having been given the location of the building, he incorporated some of the Griffin’s thinking into its design –—the idea of having the building set into the hill covered by grasslands that would allow “the people” to freely access an area above the parliament.

Angry at having to cross the old Kings Hall in the original parliament building, where they could be buttoned-holed by media and the public, the parliamentarians were determined to have a building where they could walk around freely cut off from the public.

So parliament has become a workplace that not only is in a bubble from the rest of Canberra and Australia, but most of its staff operate within a further bubble inside that. Add alcohol and 24-hour access and look what has been able to happen.

Around corporate boardrooms and in discussions among senior executives, men and women, about the sexual harassment issues in Canberra, there has been a general argument that the business community operates on much higher standards than what has been occurring in Parliament House.