From Cambodia’s killing fields to saving lives on our roads

One-time refugee Lea Ea’s journey escaping the horrors of a country ripped apart by a despotic regime’s genocide to become a world-leading transport innovator is one of spirit and inspiration.

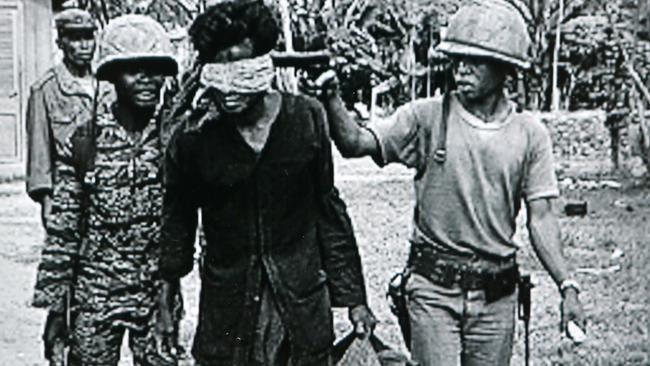

Ly Eng Ea was just five years old in 1975 when dictator Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge regime brutally took control of Cambodia, the country of her birth.

One of nine children, she and her elder sister were removed from their family and dispatched to one of the many children’s camps, where kids were trained as soldiers and brainwashed into killing their parents.

“I actually escaped quite a few times from the children’s camp, because I wanted to look for my parents,” Lea, as she is now known, recalls.

“I wanted to be with them and that was my entire being. When I was caught, I actually got punished pretty badly.”

On one occasion she was flung into a deep, fast-flowing stream and left for dead by her captors. Although she couldn’t swim, she was strong enough to dog-paddle her way to safety.

“There was another time where I actually ran away, but my father beat me up when I found him. When you ran away, you could actually get your entire family killed,” she says.

“I had no knowledge of that. I simply didn’t understand why he didn’t want to see me as much I wanted to see him.”

In April 1976, her father died from blood poisoning after cutting his hand while collecting nectar from a palm tree. Her mother, who was 36 at the time, was left widowed with nine children.

At the start of 1980 when she was nine, Ea’s family fled across the Thai border in the dead of night to a United Nations refugee camp.

“To be given food at a time when there is no food, I can’t describe it,” she remembers of life in the camp.

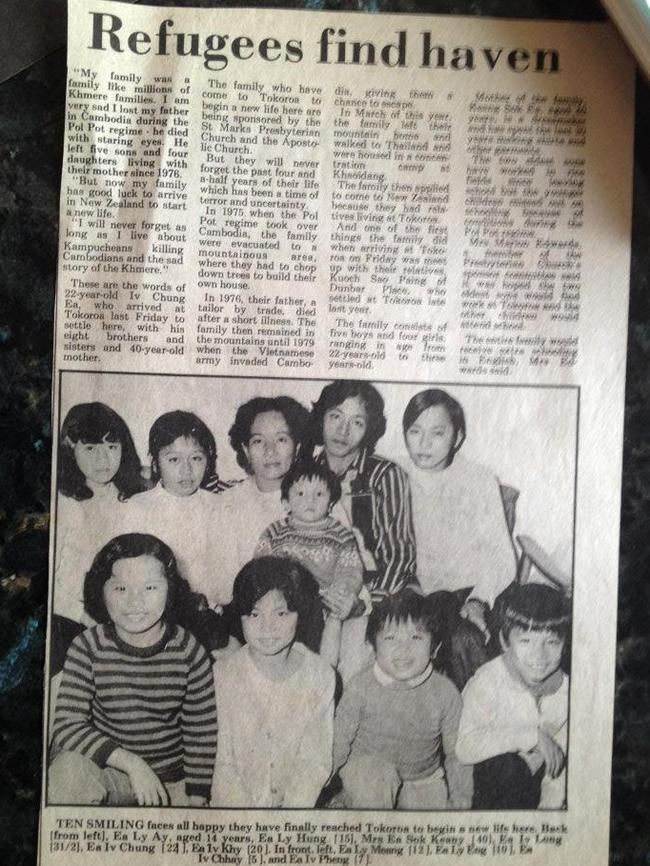

A year later the family was sponsored by two churches and sent to a remote location in New Zealand, where the 10 of them lived in a three-bedroom house. Lea shared a room with three of her sisters.

Back in Cambodia she had been unable to stop herself crying at the incessant sound of gunfire morning, noon and night. In her new home, she was grateful for the peace.

“We would not have survived but for the people that risked their lives to get us across the border, including my brother,” she says.

“They were returning the kindness my father showed to them before the war. Even though my father passed away, his spirit was still around. That kindness, that generosity, it is not something that is so common anymore,” she says.

Without any formal education and unable to speak English, she got through her schooling in New Zealand and paid her own way through the University of Auckland, where she completed a bachelor of commerce degree.

There she met her future husband, Ken, who was also from Cambodia. He lost five of his seven siblings to the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime. His youngest sister starved to death in his arms.

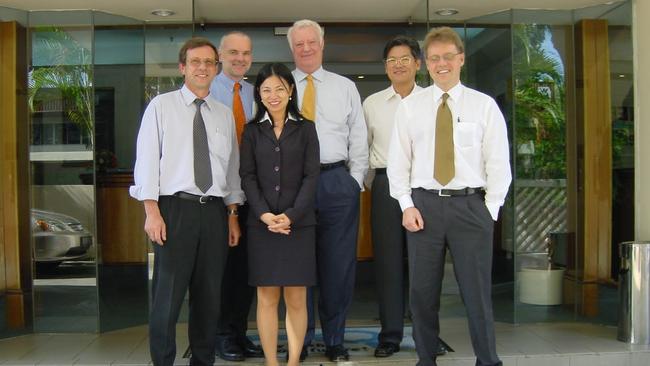

After working as an auditor in the General Audit Office of the New Zealand government, Ea

moved to Singapore to join a subsidiary of Ssang Yong Cement and then Westinghouse Technical Services, where she became chief financial officer at the age of 24.

A list of C-Suite appointments followed with Siemens Westinghouse and their many divisions, but she struggled with the politics of corporate life.

She will never forget organising a corporate golf day to raise funds for charity, despite never having picked up a golf club in her life.

While all of her fellow executives sent their personal assistants to the event, she turned up in person. To her surprise it raised $235,000.

“That taught me a lesson not to follow the norm so much, but to do the things that are in your heart,” she says.

“How I got recognised in these big companies, I guess, was because I simply loved learning, and to be humble. Not to put a corporate ladder in front of my face.”

She followed her heart again when she was headhunted for the CFO role at the luxury yacht builder The Riviera Group, based in Brisbane.

Her move to Australia was largely driven by a determination that her children should know her aunts and uncles, who had already moved to Brisbane from New Zealand.

After Riviera, she worked as the CFO at the childcare chain GoodStart Early Learning.

But her life changed forever in December 2010 when she and Ken decided to purchase a Brisbane small business named Arrowes.

It set the former refugees on a new path to becoming world-leading innovators.

Taking a business risk

When the Eas bought Arrowes, it was a small company employing just three casual factory hands and had little direction. It had a single product – manufacturing arrow boards for road traffic management – and was struggling under the pressure of international competition.

“Ken is an engineer and has passion for innovation. He had always wanted to run his own business, and he saw great potential,” Lea says.

While Ken initially focused his time on the Arrowes business, Lea divided her time between Australia and Asia, dedicating herself to charity work in Cambodia and her CFO roles at Riviera and then GoodStart.

That charity work has involved building houses with strong cement foundations for the villagers, in stark contrast to the homes made of bamboo poles that she and her family grew up in.

In 2014 she joined Arrowes full-time, the same year the firm was invited by the Queensland Department of Transport to present a safety solution at its inaugural Road Safety Innovation Hub.

The initiative was established after the death of a traffic controller in northern Queensland a year earlier. More than 100 traffic controllers are either injured or killed on Australian roads each year.

“This couple had semi-retired; they’d been married for 35 years, and he was her supervisor,” Lea says.

“He was 200 metres away when she was killed doing her job, and leading up to that fatal moment they had been talking about how unsafe it was.

“A couple of days later, she was killed by a speeding truck driver who was driving 26km/h over the 60km/h speed limit. It was so sad and even sadder it was preventable.

“At the Safety Innovation Hub, we heard about the problems in the industry, and we wanted to make a difference.”

With Lea’s strategic thinking and Ken’s engineering skills, Arrowes has diversified its product portfolio, shifting from a single focus on arrow boards to a broader range of road-safety solutions.

Today the business, called Arrowes Roading Safety, is transforming the civil roads industry with groundbreaking technology made in Australia.

Its portable traffic safety products like the eSAS, eBOOM and eSTOP offer innovative road-safety solutions which remove the traffic workers from dangerous situations.

The eSTOP, a remote-controlled portable traffic light system, has now been made mandatory in Queensland and Western Australia at high-speed and high-risk worksites.

After five years investing in research and development, Arrowe’s most recent innovation is the Automated Cone Truck (ACT), which eliminates the need for manual traffic cone placement at roadwork sites.

The ACT can deploy one cone every seven seconds, placed at intervals while the vehicle travels at up to 16 km/h.

In September the ACT completed a 12 month real-world trial on Victoria’s Eastern Freeway project, delivering groundbreaking results.

Aaron Ramsay, managing director of KPI Construction, which is delivering traffic management and planning services to the project, says: “The use of the ACT on this project has not only safeguarded the lives of our workers by minimising exposure to high-risk environments, but it has also enhanced work productivity by over 150 hours, thanks to the quicker set-up and pack-up times.”

Lea believes that like the eSTOP, the ACT will become mandated by some state governments, significantly reducing injuries and saving lives.

“The results we’ve seen so far come from a single project, but the potential impact of the Automated Cone Truck across projects in Australia, New Zealand, and globally is immense,” she says.

“We are excited to see more projects adopt this innovation and experience similar success.”

A future grounded in lessons from the past

Today Lea is executive general manager at Arrowes and her husband is an executive director working in the operations part of the business.

While they initially feared that mixing their business and personal lives a decade ago could be a disaster, she says the secret of their success has been their genuine partnership in both.

“He is just so respectful in every sense and our skills are so complementary. Where he lacks, I complement, and where I lack, he complements,” she says.

“We also don’t actually talk about work at home. It isn’t a rule, but we just don’t do it.”

Also, rarely do they talk about the family horrors that shaped them both all those years ago in Cambodia.

“There’s a lot of things that you don’t need to speak about, it is just understood,” she says.

“That is helpful sometimes because you know where each other came from and what that perspective is about.”

Lea’s mother, who turns 85 this year, lives in Brisbane. Although Lea and six of her Brisbane-based siblings take turns caring for her – they all live less than a suburb apart – the family matriarch exercises regularly and is determined to not be a burden to her children.

Twenty-three years ago Lea returned to Cambodia for the first time since her family fled to New Zealand. She says the trip was confronting.

“I wasn’t sure how my reaction would be. So I was pretty careful. When I got there, I actually met with my father’s relatives and my mum’s relatives,” she says.

“But I didn’t go and see a lot of the horrors that are actually still kept there.”

In 2013 she took her two daughters, Vanessa and Serene, there for the first time. They were then 15 and 11.

“My children grew up in Singapore and Brisbane, and they learned the history of the Khmer Rouge at school. But it was a bit more confronting for them when they saw the reality of it all,” she says.

She recalls visiting her former home with her girls, when the eldest broke down and cried.

“She said to me, ‘This is a lot more to take in than just seeing photos and being told stories. To see it in real life is quite different’,” Lea says.

Lea says she wanted her children to visit these places of such immense suffering to ensure they remembered the past and understood the horrors of war.

“It also helps you appreciate the power of the human spirit. That is something I wanted my children to know, to learn about,” she says.

But most importantly, she wanted them to appreciate the brutal reality that shaped their parents. A reality that changed them forever.

“It has impacted me in every which way. I actually say that I’m grateful. I’m blessed. Not blessed for the loss of my father, not blessed for the killing of everybody. Never that,” she says.

“But personally, I feel blessed. Just simply because I have been given a second opportunity at life. Something that not many people get.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout