From Cabramatta’s mean streets Jason Hoang rose to financial success the hard way

From a childhood of poverty and violence to financial planning stardom, Laos-born Jason Hoang has some strong words for critics of his ‘corporate image’. This is his story.

The streets of Cabramatta in the 1980s were some of the roughest in Sydney.

After then prime minister Malcolm Fraser opened Australia’s doors to thousands of refugees at the end of the Vietnam War, Cabramatta came to represent the darkest side of Asian immigration.

Street gangs roamed freely as a heroin epidemic took hold.

“Extortion and paying protection money is real. My parents had a restaurant there to make ends meet. Multiple gangs would come and ask for protection money,” recalls Jason Hoang, today regarded as a pioneer of the Australian wealth management industry.

“You had to pay, you couldn’t go to the police.”

Hoang is best known as the co-founder of a technology product called Xplan, which is now the most widely used piece of software in the Australian financial planning sector.

It was the foundation technology product for Iress, the listed firm providing software to the financial services industry around the world.

Yet while he is seemingly a natural-born leader, Hoang still has a shyness which means he struggles to make speeches in front of people.

He describes himself as an “emotional person”. But, given his history, he is proud of being so.

“I am not a McKinsey-style guy, but I have street smarts. You are either MBA-educated or self made,” he says.

“Having street smarts is incredibly valuable. I don’t conform to your corporate-type person. I don’t aspire to be, I don’t want to be.

“You can achieve in different ways. Why should I have to change to meet a profile if I can deliver the results?

“I have been asked by some people to look at my corporate image. My response to them is simple: ‘Stick it where the sun doesn’t shine’!”

Early lessons

But what is barely known about Hoang is the at-times tortuous upbringing that shaped him.

He reveals that growing up, the challenges he faced at school and on the streets spilt over into his home life.

His father was a chain smoker and an alcoholic who would regularly and on his own drink a case of beer in an evening.

“There was lots of arguing between my parents, who were under a lot of pressure. You could hear it every night,” Hoang recalls without flinching.

“There was physical violence towards me and my siblings. We certainly got very good beatings to the point where in grade six, the school principal called the whole family in.

“I would put up a fight when I was in grade 6 or 7 against my father. It was really distressing. I think that is the reason my siblings have so much love and care for me. My mother is the most resilient person I have ever seen.”

But Hoang has never held a grudge against his dad.

“I love him to bits. I am what I am today because of what he did for our family,” he says proudly.

His parents, Canh and Dong, are now both 72 and happily living in Canberra.

“I got to understand what kind of pressure my father was under as a 20-something year old with six kids in a foreign country, while being discriminated against as he worked, 20 hours a day,” he says.

Hoang was eight years old when his parents brought their family to Sydney from the tiny Southeast Asian nation of Laos.

But by the late 1980s they were on the financial brink. They could no longer afford to pay off the Cabramatta gangs.

Their solution was to move to Canberra, where they would reunite with close family members who had also fled Laos.

It would change Hoang’s life.

In 1991 he started tertiary studies at the University of Canberra – the only institution that would accept him.

After a year doing computing studies, he spent the next three completing an accounting degree.

After graduating, the only job he could secure was with William M. Mercer as a super fund administrator in Sydney. Two weeks later, he was joined at Mercer by a fellow named Andrew Walsh.

They instantly saw the opportunity to transform the way advisers delivered advice to their clients through an innovative approach to data, digitisation and automation.

“From there we built this close relationship over the next few years together. We could see we had the smarts and tenacity to go out on our own – to build the first piece of internet-based financial planning software,” Hoang recalls.

After moving to Singapore and over many meals of chilli crab at the city’s famous Jumbo seafood restaurants, they came up with the idea for Xplan.

“It was the first of its kind to go internet based. It was a huge gamble because it was still dial-up internet for a lot of businesses back then. But we knew we could cater for all the different needs of the planning business,” Hoang says.

“The flexibility allowed us to get in front of companies that we would not normally have got in front of.”

They were instrumental in transitioning Xplan from an independent start-up to a fully integrated division of Iress. Hoang became managing director of Iress Asia in August 2010.

“We got $7m in cash and equity in Iress for selling it,” he says.

“The biggest thing was relief. I remember my wife taking a photo of the bank account at that time. That made me really, really proud. Outside the birth of your children, I could not think of a prouder moment.”

But he says the wealth he generated from the deal did nothing to change him. He spent 10 years based in Singapore running the Iress regional trading business.

Nine months ago then new Iress chief executive Marcus Price appointed Hoang to run and transform the APAC Trading and Global Market Data division of the firm.

“Now I am driven to make success for the eight leaders in my team,” he says.

“If they can talk about me when they retire as a person who has shaped their careers, that will make me very proud.”

Light at the end of the tunnel

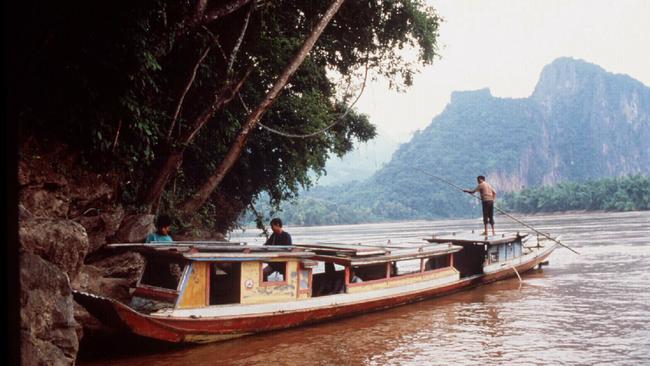

After they left Laos and before they moved to Sydney, Hoang and his five siblings – two boys and three girls – spent two years in a Thai refugee camp.

His father, a trader, had met his then noodle-selling mother on a street corner in Laos.

Canh Hoang spoke many languages, which made it easy for him to barter. But given the ongoing Laotian civil war, he knew there was no future for his family in the country.

He sold all the assets he had and paid off a military general to get his family across the border to Thailand.

“A big stroke of luck was to get through the first stage, to not be killed before you crossed the Mekong river. My mother was eight months pregnant with twins too,” Hoang recalls.

Yet when they arrived, the conditions in the Thai camp were horrific. There were malnourished children at every turn.

Hoang looked outside the border fence for sustenance, where people had thrown half-eaten food into rubbish bins.

“I would dig a hole under the fence at dusk, take the food and bring it back to the family” he says.

Each morning, an announcement was made by one of the guards listing the names of the individuals and families who would be repatriated to Australia. Many were Vietnamese.

Being from Laos, the Hoang family had no links to the Vietnamese community.

So Canh Hoang created Hoang as a Vietnamese surname and changed the family’s identity. Within three months their names were called to make the aeroplane trip to Sydney – their first ever flight – to live at the Villawood Detention Centre.

Hoang looked after his siblings, including his youngest sister after her birth, straight out of hospital, while his parents left the centre each day to work themselves to the bone.

“There was one incident in Villawood that shaped my thinking on how bad people could be.

Another family had enough money to have a TV and my five siblings would climb on milk crates to peek over the window to watch the TV,” he says.

“The mother there closed the blinds one day. I was shocked. I never ever wanted that to happen to us again.”

The family was sponsored to move to Cronulla on Sydney’s southern outskirts and took a rental property on busy Presidents Ave. Hoang and his siblings went to the local Catholic school up the road, where he was mercilessly bullied.

Every day they would take peanut butter sandwiches for lunch because that was all they could afford.

He got into fights most days by standing up for himself and his siblings, for which he was caned at school.

“I remember I watched a group of kids playing rugby league one day. I thought ‘Here’s my chance to belt a few guys back.’ I rocked up to training with no fear. I tackled everything in front of me and after a while, I got really good at it,” he says.

“I suddenly felt respected. The bullies welcomed me because I was better than them.”

His talent on the field resulted in Hoang and his family being selected to attend the Westfields Sports High School in Fairfield – the nation’s first selective sports school. More than 20 of the school’s students have represented Australia.

After switching codes to rugby union, Hoang in later life captained Singapore at the Touch Rugby World Cups in Scotland and Australia, and represented his state team at the Australian Touch Rugby national titles.

“That was a way out,” he says of his Westfields experience. “We saw a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Choose your destiny

If Hoang’s business career could be divided into three, he says he is now at his third and final stage.

Its genesis goes back to a leadership offsite last year at the famed Chateau Yering in Victoria’s Yarra Valley, when Price asked him to choose the business he wanted to run.

“I knew the easiest one would be wealth and the hardest to turn around would be trading and market data,” he says.

“It was too crucial a business to get wrong. I thought ‘If I can’t make it a success, with all my connections in the company, no one else can.”

He presented a clear strategic road map to the staff and actioned it.

So far so good. Since last April, the APAC trading and global market data business has exceeded its forecasts, despite the broader firm continuing to be challenged. It announced a shock profit downgrade last September before Price formally took the reins.

In late November Price, who has been returning the firm to its core and cutting staff, claimed Iress had improved customer sentiment and reduced costs.

“It has been down to accountability. With the previous structure under one Iress, there was no accountability. There was always previously an out if you didn’t achieve something,” Hoang says.

“Now under the business unit structure, the outcome has to be delivered and you have complete autonomy within the business to get there.”

He describes Price, the former head of the nation’s biggest e-conveyancing operator PEXA, as a “different type” of leader.

“He is old school in how he does things but he is a good strategist and I don’t want to let him down. He doesn’t play politics, he plays it straight. You are shit or you are good. I enjoy that,” he says.

“Sometimes you have to cut to the chase. I enjoy that frankness.”

Hoang, who has been married to wife Jessica since 1998 and they have two children studying physiotherapy at the University of Canberra, says he will never forget the day he was appointed to his new role last April.

One of his new staff members approached him, in tears.

“She told me that having an Asian person lead the business meant so much to her,” he says.