Clarity and humble beginnings that drive Clarity Pharma chair Dr Alan Taylor

Alan Taylor’s youth, spent around a Redfern block now notorious for one of Sydney’s most brutal drug-related murders, shaped his career trajectory from banker to successful biotech leader.

Moments of supreme clarity have shaped Dr Alan Taylor throughout his life.

He once worked as an investment banker until he realised he was missing too much of his young family growing up.

He had a budding career with NRL club the Sydney Roosters but accepted he would never quite make it into the senior side.

But it was the death of a beloved grandmother from an incurable cancer which brought him perhaps the greatest sense of clarity. Today the company he chairs, ASX-listed biotech Clarity Pharmaceuticals, has a market value of about $1.5bn and if he has his way, it will revolutionise how we treat such insidious diseases.

The formative years of the young Alan Taylor can be traced to his childhood in the Redfern accommodation block years later more notorious for one of Sydney’s brutal drug-related murders – unit B31 of the McKell public housing block at 55 Walker St in inner Sydney.

When the bland, soulless building opened in March 1964, then former NSW premier William McKell – who it was named after – described it as a “magnificent block of units”.

Half a century later, unit B31 was the scene of the slaying of famed drug dealer Daniel McNulty. Harriet Wran, the daughter of another former NSW premier, Neville Wran, spent two years in jail for her role in the killing.

Yet despite its horrors, unit B31 always held a special place in the life of Taylor.

After emigrating from the island of Malta in Southern Europe after World War II, his grandparents were some of the first to move into the McKell units in the early 1960s and lived there for the next three decades.

They had moved to Sydney with their life savings and the dream of buying a home, but lost it all when they gave it – ironically – to a Maltese real estate agent, who stole it.

It condemned their family to relying on the government to put a roof over their heads.

Taylor’s earliest memories as a child were living with his parents on the 14th floor of the Daniel Solander building in the Waterloo public housing complex, 10 minutes’ walk from McKell. For decades the Waterloo complex was colloquially known as “Suicide Towers”.

On most weekends and holidays, he would visit the McKell units to see his grandmother named Caroline, now the middle name of his eldest daughter.

“Because we had no money, I had two working parents. When I turned up to my grandmother’s apartment, it was always a really happy time. I’d walk in and she would hug and kiss you. She’d always been cooking because that’s what Maltese grandmothers do,” Taylor recalls.

Eventually his parents moved to housing commission accommodation in South Coogee and Taylor split his time between there and Redfern.

But one of the hardest moments of his life came when he was in his early 30s and completing a PhD at the prestigious Garvan medical institute in Sydney.

His grandmother was diagnosed with incurable lung cancer and given six months to live.

Over the coming weeks and months he spent all the time he could with her, learning her stories from the war, including tragically losing her sister during a bombing raid.

On the day she died in 2004, Taylor was at the movies. During the film, his mother had sent him a string of increasingly panicked messages but his phone had been switched off.

“When I eventually read them I headed straight there, but my grandmother was already gone. I didn’t get to say goodbye,” he says slowly, his voice momentarily breaking. He looks away to wipe away a tear.

“She was a strong woman, such a powerful influence. That was a very difficult period because I was the smartest kid at university, yet I would feel so useless because there was nothing I could do for her.

“That probably relates to where I am now, having a focus on the translation of science, to try and help people not to be in that situation where you feel so helpless; where science is one of those things that gives you an opportunity to change the outcomes for people.”

His maternal grandmother’s experience and later watching his paternal grandmother’s debilitating battle with dementia for many years inspired Taylor to focus on getting Australian science out of labs and to patients.

In 2013 he joined Clarity Pharmaceuticals, a firm that has pioneered new forms of cancer treatment through radiopharmaceuticals using copper in order to pinpoint and better treat tumours with precision.

Since then he has been on a mission to get the company’s copper technology funded and into clinical trials.

Clarity shares are up a stunning 75 per cent in the past month after it revealed that the first prostate cancer patient dosed with two cycles of its revolutionary drug, known as 67Cu-SAR-bisPSMA, achieved a complete response to treatment.

The patient, suffering metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CPRC), had previously failed hormone therapy, an investigational agent and chemotherapy.

The five-year survival rate for metastatic CPRC is currently only 30 per cent.

“Having that dramatic response is incredible because we have built the product from scratch,” Taylor says of the trial, known as SECuRE

“We hope to replicate this remarkable result in many patients, and confirm the favourable safety profile of this agent.”

Given a sporting chance

Taylor’s parents spent all the money they could save to send him and his brother to Waverley College, where he discovered his love of sport.

“My parents are incredible. They did everything for us and were really, really important to the whole story,” he says. They are both still alive today, living in Newcastle.

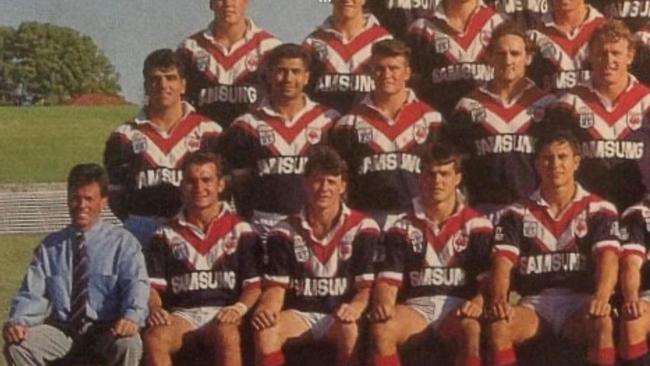

After growing up playing rugby league with Indigenous kids living in and around the Waterloo public housing complex, Taylor joined the Sydney Roosters as a junior and progressed through the ranks to play as a professional until the age of 23.

He trained with the senior squad and played in the reserves, but never quite managed to crack first grade.

When his league career ended he focused on exercise and the way the body worked to gain a performance edge, and in 1997 began an undergraduate degree in applied science at the University of Sydney, where he finished first in his year and won the prestigious University Medal.

He then completed a PhD in medicine, but halfway through decided to simultaneously start a finance diploma at the Financial Services Institute of Australasia.

“Everyone was telling me science was just publish or perish. It is not. It is a whole continuum of changing the lives of humans. Science should benefit humanity,” he declares.

The diploma led him into investment banking with a boutique advisory firm named Inteq specialising in life sciences M&A and corporate advisory.

“I moved from basic science undertaken at research institutes to translational science, that brings science to the patients that need it most, This, due to funding structures, occurs in companies,” he says.

Over 13 years he was involved in nine IPOs and advised on $2bn worth of transactions, but one evening an experience with his eldest daughter told him the time had come to get out.

“I had a couple of kids at the time and investment banking back then was very different to what it is now. There was no work from home. You had to be in the office from 7am and maybe you could leave by 8pm on a good night,” he says.

“I remember one night rushing home early just to read my eldest daughter a book. She was five at the time. When I got home I told her ‘I can read you a book tonight’. But she just cried, ‘No, I want mummy to’. That’s when I said to myself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ I wanted to be a dad.”

After taking senior roles within various companies, Taylor raised more than $1m for a new start-up biotech company based in his old neighbourhood of Eveleigh.

In 2013 he joined Clarity when there was only a single founder and two provisional patents. Eight years later he led the firm through its IPO.

Clarity’s share price has risen from 49c in May 2022 to now be trading well over $4.40, giving it a market capitalisation of nearly $1.5bn.

“I did it because people said we could not do it. They always said the commercialisation of science is appalling in this country. So I wanted to build a precedent. I left my career to build a precedent,” he says.

“Our goal has been to be the most successful homegrown life sciences company that hasn’t had to rely on venture capital. Every one of our private and public funding rounds has been done with ordinary equity.”

The latest in April was a fully underwritten equity raising of $121m, the first since its IPO, taking the company’s cash position to a healthy $150m.

Its shareholders include Argo Investments, Antares Capital, Thorney Technologies and the Perennial Future of Healthcare Fund.

Funding from the capital raising will support ongoing research and development, and the clinical trials of Clarity’s therapeutic and diagnostic products in Australia and the United States.

A sense of clarity

Clarity now has five open investigational new drug (IND) applications with the FDA, covering all six current clinical stage products that have received clearance to proceed to clinical trials.

It has also received approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration for two orphan drug designations (ODD), and two rare paediatric disease designations (RPDD).

But there is an extra personal motivation for Taylor to secure regulatory approval for Clarity’s drug to treat prostate cancer.

His father, who is now in his 80s, was diagnosed with the disease eight years ago.

The surgeon he initially saw at Sydney’s Prince of Wales hospital, in Taylor’s words, “just wanted to cut”.

“Dad came to me and said ‘Look, I don’t feel comfortable with this. What can I do’?” he recalls.

Taylor reached out to Royal North Shore hospital, where an old friend and colleague was running a trial of external beam radiation to treat the disease. He was happy to treat his dad.

It has meant he avoided life-changing surgery. Now, with 67Cu-SAR-bisPSMA, Taylor hopes he can get a drug approved which may further prolong his dad’s life.

“I remember him asking the clinician over at Royal North Shore what was going to happen. He replied ‘Well, you have this condition and you will probably live for the next 15 years, then die a painful death.’ But in my mind I was thinking ‘Maybe you won’t!’,” he says with a wide smile.

“At Clarity we want to be that next iteration of therapies to hopefully maintain, improve or have better outcomes in the quality of life for patients in real time. Whether it’s kids or adults with cancer.”

Taylor and wife Sally now have three teenage children.

In between leading Clarity, he competes in and wins international competitions in Jujitsu, a family of Japanese martial arts. His eldest daughter has now taken it up.

In April they travelled to Brazil for the Brasileiro, the Brazilian Nationals, which is considered to be the toughest tournament in the world.

Back home, Taylor hasn’t forgotten his roots.

Clarity has launched a partnership with a charity called Story Factory, a not-for-profit creative writing centre for young people in under-resourced communities across Sydney and NSW.

It is helping Story Factory to recruit Indigenous storytellers to provide writing programs to Indigenous young people.

Story Factory has worked with thousands of young Indigenous people since opening in 2012 in Redfern, not far from the Clarity head office in nearby Eveleigh.

Taylor’s stake in Clarity might be now worth more than $90m, but he will always remember that it started with virtually nothing.

He also knows that all the money in the world will never buy more time with his children. Or bring back his beloved grandmother.

“I never had anything. My parents raised my brother and I with nothing. So when you are jumping into something and there is nothing, what did I have to lose?” he says proudly.

“I was able to follow a passion and a dream. It gave me the strength to throw everything in. Because I know there is a way when people have nothing.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout