Can embattled AMP outlive the curse of Circular Quay?

For decades AMP management has had possibly the best view in Sydney. They should have been looking inside instead.

When David Murray took the chair of the AMP in May 2018, he became the third chairman to be required to rescue the Australian savings icon in three decades. The first was the late James Balderstone, who in the early 1990s teamed with then CEO, the late Ian Salmon, to rescue a mutualised AMP that had issued capital guaranteed securities during a war with National Mutual.

These capital guaranteed securities were backed by property and shares (led by Westpac shares) that slumped in value. We nearly lost the AMP.

Then after AMP became a public company it incredibly made the same mistake again, this time in the UK.

Once again a slump in asset values had the AMP on its knees. Peter Willcox, who had revamped BHP‘s oil operations, took the chair, and with CEO Andrew Mohl rescued the company. Again it was a close thing.

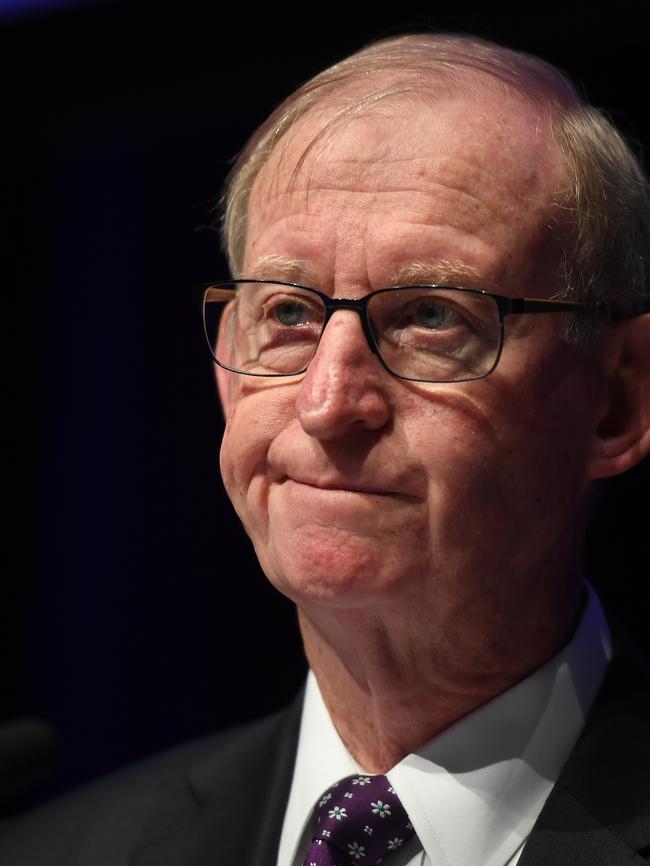

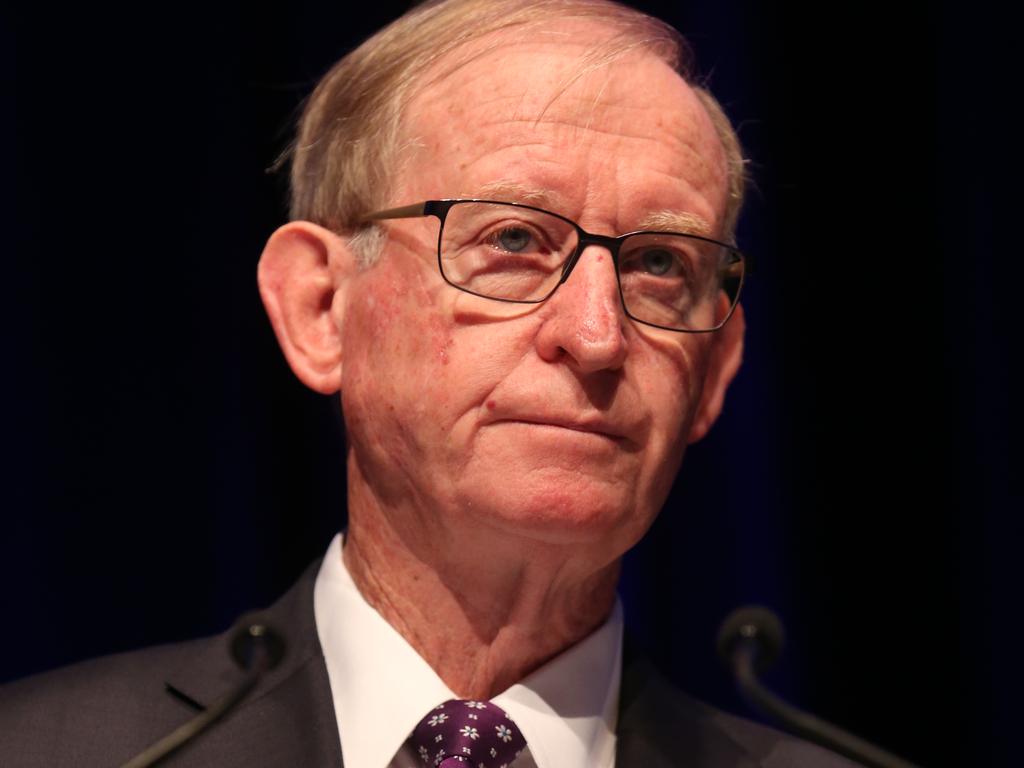

Fast forward to 2018 and AMP had lost its chairman and CEO over cover-up allegations and faced the real danger of a massive exodus of funds. The appointment of a person of Murray’s calibre as chairman steadied the ship

The great savings institutions of the twentieth century – AMP, National Mutual (now owned by AMP) and MLC – have created incredible turmoil as they struggle to find a way forward in the 21st century.

The investment world is now focused on AMP’s sexual misconduct but there is also a much deeper set of problems that require addressing. That’s where Murray placed his focus.

I am glad David Murray stood down as chairman of AMP rather than being dragged through the mud trying to sort out the sexual misconduct issues. David Murray was one of the great Australian banking chief executives and he set up the Commonwealth Bank up to become the most successful of the big Australian banks.

On “retiring“ he helped propel the Future Fund into one of the most successful of Australia’s investment institutions and his report on Australian banking greatly improved the capital integrity of the Australian banking system.

But in my view – and David Murray would disagree – he had a weakness. Murray believed that there was a strong future for the life office movement in Australia, particularly if combined with a bank. And so in 2000, CBA, under Murray, paid almost $10 billion for Colonial.

Former Colonial boss, the late Peter Smedley, was over the moon with the price but Murray believed it would deliver great rewards for CBA shareholders. He shifted the head office to Sydney but the management talent of the bank did not extend to being able to deliver the anticipated rewards. NAB followed the Commonwealth and purchased MLC. But the NAB management strategy was totally different to CBA. It left the head office in Sydney and allowed the MLC to continue to operate independently and even bank with Westpac.

When Andrew Thorburn became NAB CEO in 2014 he sent Andrew Hagger into MLC to discover what had been going on. Hagger discovered that the high commission selling system that built the great life offices had been transferred into financial planning via the charging for services that in many cases were not provided. AMP had a similar strategy. Hagger discovered that in reality, commissions were still being charged, but under a different name. MLC management escaped the wrath. Instead it was NAB’s Hagger, Thorburn and chairman Ken Henry who lost their jobs.

Colonial encountered its own version of this problem and savers lost large sums.

The high commission life office selling system was not a problem in the twentieth century but the savings rules have changed. Murray’s task at AMP was to make sure that this time AMP really adapted to the 21st century.

AMP also has a special management problem. I remember going to the AMP head office at Circular Quay in the 1960s and being stunned by the views. When you were in that office and the subsequent one behind, it was as though you were separated from the wider world. That isolated the management and contributed to the three crises that followed, any one of which would have destroyed a lesser brand. .

And the world saw the insulated management that Circular Quay generated in the Hayne banking inquiry, which triggered a substantial loss of money under management. But a large number of companies, along with individuals, stayed with AMP in the belief that the great David Murray and his people would get AMP through to the other side.

Now he’s gone and fascinatingly it’s reported that some of the AMP’s great rivals among the industry funds were part of the shareholder push to make life difficult for David Murray.

But there is a separate long-term issue which also leaves AMP vulnerable. For years the Coalition has been pressing to stop unions being able to stipulate in enterprise agreements that employees must invest their superannuation money into the industry funds linked to the union. It was a totally unfair practice but changing the legislation was difficult.

But Superannuation Minister Jane Hume successfully steered “freedom” legislation through the parliament this week. It was paradoxical that the bill should go through at the very time that Murray stepped aside. AMP superannuation members include employees where employers have chosen AMP, but there is unlikely to be a herd like stampede to the exit. But the controversy would not want to continue on for another year or so. And if AMP ever gets its act together and one or two industry funds stumble there is now an opportunity for the icon to make a comeback. But internal fighting must stop.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout