James Wolfensohn obituary: 1933-2020

James Wolfensohn had one of the most remarkable careers of any Australian ever. He was the greatest ‘Renaissance Man’.

Not many Australians receive a personal assurance from the prime minister that they can have their citizenship back. James Wolfensohn, long before he became a public figure as president of the World Bank, was already a star of the Australian diaspora.

“I would be grateful, I said, if it were to be noted in my file, in his handwriting, that if I wanted my citizenship back, I could have it,” Wolfensohn later said, referring to conversations with prime minister Malcolm Fraser in 1980.

Already on the short list in his mid-40s to succeed Robert McNamara as World Bank President in 1980, the Carter White House expedited his citizenship, granting it within a fortnight. Wolfensohn later wrote it was “with great reluctance” he became an American. Convention dictates the World Bank be led by a US citizen, while a European leads its sister organisation, the International Monetary Fund.

His death on November 25 ends one of the most remarkable careers any Australian has ever had, certainly in the world of banking.

Financier, musician, Olympian fencer, Wolfensohn excelled at whatever he did. He was surely the greatest Australian “Renaissance Man” of his generation, maybe ever.

He wasn’t ultimately successful, though, at becoming a grandee of global development until 1995, by which time, a fixture of New York society and sporting a knighthood from the Queen, he was the obvious choice for US president Bill Clinton to take up among the most plum of positions global bureaucracy has to offer.

By then juggling the Chairmanship of the John F Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and his own investment bank, Wolfensohn’s closest political friends were Democrats.

At the World Bank he championed debt relief and fought corruption. “I was able to build a life that has been global, to travel to more than one hundred countries, and to both witness and participate in the changing economics and demographic balance of our planet,” Wolfensohn would write.

He marshalled the Bank’s significant intellectual and financial resources – it doled out US$43.8 billion in 2017 — to push back against the first wave of anti-globalisation protests which took off in the late 1990s.

Wolfensohn’s extraordinary ascent wasn’t aided by family connections or money, but his parents inculcated a love of European literature and classical music. His Belgian mother, Dora and English father, Hyman, both Jewish, came to Australia in 1928, five years before James was born, with their five-year old daughter, Betty.

They were cultured and well connected, his mother a keen pianist and his father, trained as a barrister, would eke out a business in Sydney that advised new Jewish immigrants.

His father had fought in World War I in a special Jewish unit of the British army, as it happened, alongside David Ben Gurion, who became the first prime minister of Israel.

Later he became private secretary of James Rothschild, whose affections extended to ensuring he and Dora were driven around Berlin in the Kaiser’s Rolls Royce on their honeymoon.

In his autobiography Wolfensohn lamented never divining why his taciturn father suddenly left Rothschild’s employ and migrated to Sydney, settling in Ocean Street, Edgecliff, in Sydney’s eastern suburbs.

Precocious, Wolfensohn nevertheless failed his first year at the University of Sydney after attending Sydney Boys High School and worked part-time in a lumber yard and later as a shoe salesman at David Jones. He graduated in arts and law in 1957. He took up fencing, captaining the university team at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne.

His self-confidence and poise were well apparent in his 20s. Missing out on a Rhodes scholarship, and the application date for a scholarship to Harvard, he succeeded in convincing the federal minister for the air, whom he had phoned cold, to send him to the US for free on an airforce plane for an interview.

He graduated with an MBA in 1959 along with Rod Carnegie, who would also distinguish himself. “Coming out of Harvard he could read a business plan at 100 metres and could do exactly the same for a balance sheet,” says Tom Quirk, who worked for Wolfensohn in the 1980s.

Returning to Sydney, he quickly progressed at investment bank Darling and Company, recruiting Mark Johnson, who became a prominent Australian businessman, and David Clarke, later chairman of Macquarie Bank, in 1966.

“David [Clarke] and I used to follow Jim’s career and we thought of him as a trapeze artist, because every time he took a daring swing and we thought he must drop into the net, he ended up on a higher bar again,” says Johnson.

A spat with a senior colleague saw Wolfensohn move to parent bank Schroders in London, one of the leading British investment banks at the time. Passed over for promotion after the chairman, Gordon Richardson, became Governor of the Bank of England in 1973, Wolfensohn spat the dummy and moved to New York. “It wasn’t because I was Jewish, it wasn’t because I was Australian, it’s just that I wasn’t going to get it, they told me,” Wolfensohn would tell friends later. “On talent and record he was probably the best candidate,” says Johnson.

He joined Salomon brothers, where he rose similarly quickly, helping save Chrysler from bankruptcy in the early 1970s. He revelled in New York’s networking and business opportunities, becoming very rich along the way. “I remember being taken by Jim out to world’s most expensive hamburger, US$55. And that was in the mid- 1980s!” recalls Quirk.

There he met his wife, Elaine, an American with whom he had three children Sara, Naomi, and Adam. Falling out with Salomon, he set up his own bank, James D. Wolfensohn, Inc., in 1981, making recently retired Federal Reserve chairman, the great inflation fighter, Paul Volcker its chairman. “It gave Jim instant status, and tremendous access,” Johnson reflects.

In the meantime he became chairman of Carnegie Hall, saving it from demolition. He advised Bob Hawke on how to impose sanctions on South Africa, which helped lead to the demise of the apartheid.

“He’s very good with people. He once said to me, in what I regard as piece of very insightful personal analysis, ‘you know I’m lucky that I’ve been born with a personality that a lot of people like’,” says Johnson. “To see Jim cruising the room at an IMF meeting was almost a work of art,” he adds.

His firm was sold to Bankers Trust for $US210 million soon after he started at the World Bank. He gave half of his share, around $US50m, to his charity the Wolfensohn Family Foundation. “He was ambitious in areas where a lot of wealth could be accumulated, but that wasn’t his prime objective. His prime objective was to succeed in being Jim. And to show the world that Jim could do it,” says Johnson.

“Equity and social justice became part of my vocabulary and a growing focus of my activities,” Wolfensohn wrote. The Bank became his “challenge and passion”. The distinguished journalist Sebastian Mallaby devoted a 462-page book to Wolfensohn’s transformation of the World Bank over the decade to 2005. It was a mix of admiration for his genuine passion and energy for improving the lot of the world’s poor, and criticism of his ego, style and arrogance.

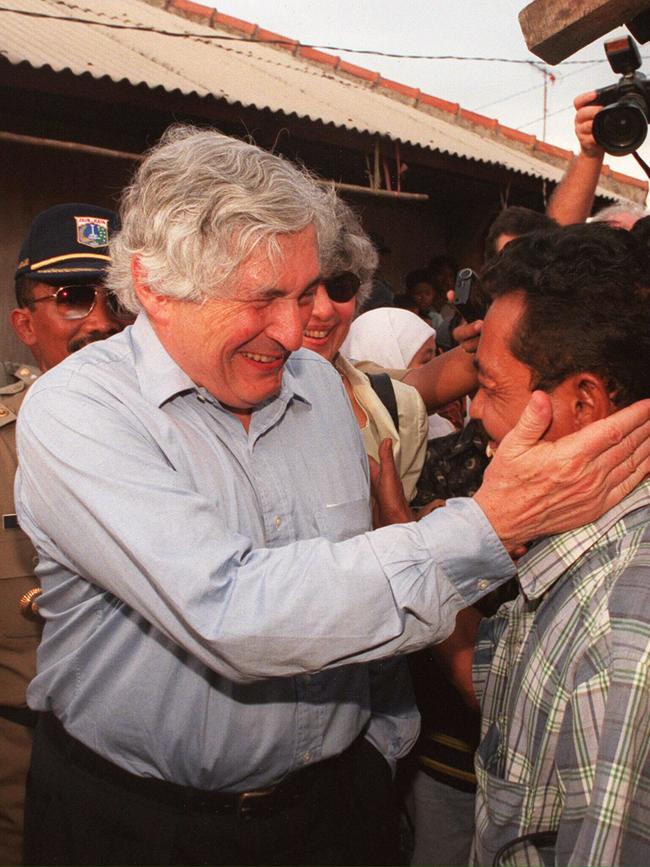

He threatened to resign unless he was given a private jet. He could be direct: “You’ve really fucked this country up,” he told the Bank’s local director, alighting from his jet on Jakarta tarmac in 1998 during the Asian financial crisis. His staff were loath to upset him. Mallaby revealed how he visited a small village in the Indonesian jungle where the villagers were in fact Bank staff bussed in from the nearest Sheraton. Whatever the verdict, he was a superior president to his predecessor, Paul Wolfowitz.

He pushed an unwieldy 10,000 strong bureaucracy to think more creatively about how to alleviate poverty. He walked the talk, spending more time abroad in poor countries than previous presidents and expecting his staff to do the same.

Along with development, music animated this life. Wolfensohn took up the cello in 1975, in his early 40s, as a way of consoling the distraught cellist Jacqueline du Pre, whose brilliant career came to a precipitous end in the wake of a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. He would practise daily at 6am or midnight. He became so good he performed alongside top cellist YoYo Ma at Carnegie Hall to mark his 70th birthday. “He used to take two seats on the plane, one for his instrument; he was carting it around well into middle age,” says Quirk. Like his friend Paul Keating, he collected French empire style clocks.

Ever industrious, after leaving the Bank he became Chairman of the International Advisory Board of Citi, a giant US investment bank. He founded the Wolfensohn Center for Development at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC.

In 2010 he wrote an autobiography, “A Global Life: My Journey Among Rich and Poor, from Sydney to Wall Street to the World Bank”.

“During the more than half century of my professional career, the whole world of international finance changed,” he wrote.

He later lamented that his last public engagement, at the behest of the United Nations, the US, and European Union, to fashion an agreement between Israel and Palestine over the Gaza strip, ended in failure – “my mission impossible”.

He did, however, regain his Australian citizenship in 2010.

It’s a pity he didn’t expand on the causes or consequences of the global financial crisis.

“For me and others like me from many countries it presented the chance to become a global player, to feel more of a citizen of the world than a member of one nation,” Wolfensohn wrote. In a time when globalisation faces ever greater political challenges, a life like his might be as rare this century as it was in the last.

James Wolfensohn

Born: Sydney, Australia, December 1, 1933

Died: New York, USA, November 25, 2020

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout