Jaded iron ore producers hit the pain barrier

THERE is nothing psychological about iron slumping to below $US80 a tonne.

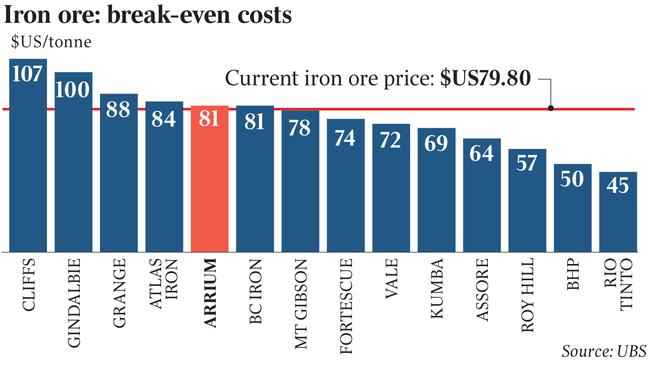

THERE is nothing psychological about iron slumping to below $US80 a tonne. But it can be thought of as a pain barrier given the number of local producers that cannot turn a buck at these prices rises to alarming levels.

At yesterday’s closing spot price of $US79.80 a tonne, as measured by The Steel Index, question marks are raised about the long-term economic viability of all but three local producers.

Those on the right side of the $US80-a-tonne barrier are Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton and Fortescue. But the rest of them — Atlas, Gindalbie, Grange, BC Iron, Arrium and Mount Gibson — will be finding the going tough if prices remain at these levels, with the only current offset being a welcome fall in the currency.

From a national economic perspective, it is a good thing that the vast bulk of the nation’s iron ore exports are in fact locked up with the operations of Rio, BHP and Fortescue.

But as the thrashing of their share prices in recent days demonstrates, the replacement of last year’s 200 per cent margins with more sedate 70 per cent (Rio and BHP) and 10 per cent margins (Fortescue) means their elevated profits of recent years are fast becoming a distant memory.

Canberra should be getting nervous as the slump in profits from what has been the only seriously profitable component of the mining industry means that tax receipts and royalties are now also under pressure.

At its current spot price, iron ore is at its lowest level since September 2009, a year after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, an event that marked the onset of the global financial crisis. That is not to relate the collapse in iron ore prices — they averaged $US135 a tonne last year — to a GFC-like event.

The collapse in prices is all about the economic slowdown in China, the world’s biggest consumer of the steelmaking raw material, at a time when the Pilbara producers in particular have been adding mountains of low-cost supply (to capture those now gone 200 per cent margins) faster than demand has warranted.

It has been clear as day for the last couple of years, but the producers and sell-side equity analysts have clung to the thematic that Chinese steel production — already the world’s biggest by a massive margin — would continue to grow hand-over-fist and absorb the new capacity without damaging the iron ore price.

Recent events have proved that wrong, and there have been voices telling us so. Most notable was the recent warning from former senior BHP executive Alberto Calderon that Australia faces a permanent fall in prices as growth in the Chinese economy becomes increasingly driven by private consumption.

The Yale-trained professor of economics — one of the contenders for the top job at BHP that went to Andrew Mackenzie — said it was not difficult to see why iron ore prices have collapsed and why they will go even lower, tipping a retreat to the low $US70s a tonne for several years.

There has been plenty of headshaking among the Chinese too on the narrative in this market that a rebound to $US100 a tonne was a deadset cert. Time after time there has been commentary that $US80 a tonne was about right. But no one here wanted to listen.