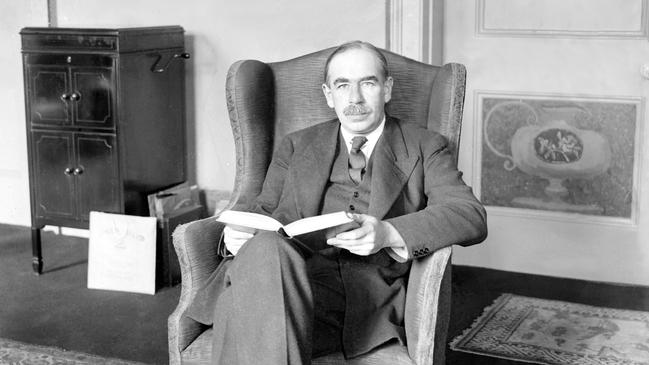

Investors could learn from economist John Maynard Keynes - and Winston Churchill

Two of the towering figures of the 20th century were both big investors. One was a clear winner.

John Maynard Keynes is the economist who effectively designed the world in which today’s investors operate: your artificially low mortgage rate, the latest trillion-dollar stimulus in the US and our own JobKeeper program can all be traced back to his influence.

He was also one hell of an investor.

Many Australian investors would find fault with his economic theories, but they would also admire Keynes — the active investor — because he backed himself time and again during very difficult years.

A brilliant and well-connected academic, he began as a speculator in the 1920s and initially did very well in a period that looks very much like our own, where new technology companies (auto and aircraft companies) spurred a speculative boom on wider markets.

In 1928 he had amassed a fortune of £44,000 but after the Wall Street crash of 1929 his fortune had shrunk to £8000.

It is how he rebuilt his position and became a convert to what we now call value investing that is the kernel of the story. Over the next three decades Keynes evolved a system of watching and waiting for stocks he believed were undervalued by the market. He called them “stunners” and once he fixed on a bargain he went in big time.

As Justyn Walsh says in “Investing with Keynes”, he completely inverted his investment principles to focus on likely future performance rather than past trends, expected yield rather than disposal prices, particular stocks rather than the broader index, and relying on his own judgment rather than that of the market.

Keynes was a conviction investor keeping a relatively small amount of individual stocks which he understood inside out. “I believe now that successful investment depends on (among other things) a steadfast holding of fairly large units through thick and thin, perhaps for several years,” he told a Cambridge University committee in 1938.

So what can we learn today from Keynes? In common with the best-known investor of our own time, Warren Buffett, Keynes was not unaware that many people simply can’t understand the markets. Though he was an active investor he thought those who struggled to operate in the sharemarket should allow someone else do it for them. Indeed, Buffett has regularly suggested some investors would be as well off passively investing in index funds; Keynes would have agreed.

But for active investors he had guidelines based on fundamental analysis of profits and dividends and focusing on a small selection of stocks. On one occasion — acting for the Provincial group — he put the firm into a substantial position in a company called Elder Dempster. When quizzed by a board member on the large position he had taken, Keynes wrote back: “Sorry to have gone too large in Elder Dempster … I was … suffering from my chronic delusion that one good share is safer than 10 bad ones.”

New research shows that in the 25 years Keynes ran the Chest Fund at Cambridge University the fund made 16 per cent per annum versus its benchmark index of 10.4 per cent.

As Keynes got older he got more certain of his investing principles and got better results — he also traded less.

In essence his three great principles were: a careful selection of a few investments; a steadfast holding of such units until they fulfilled their promise or it became evident they were a mistake; and a balanced investment position with interests beyond shares, such as gold, to achieve some diversification.

In reading Investing with Keynes, which could have had the subtitle “how to invest carefully”, I’m reminded of another recent book on the financial adventures of another great name from the same period: David Lough’s entertaining 2015 book “No More Champagne (Churchill and His Money)”, which might as easily been called “How not to invest … ever”.

Winston Churchill and Keynes had similar advantages and a similar background — privileged high-income earners with impeccable connections (Churchill was the world’s most popular non-fiction author in the 1930s).

Before he was prime minister, Churchill had been Chancellor of the Exchequer (treasurer) in Britain but he was the opposite of a value investor — he was an incorrigible gambler on both the stock exchange and at the casino.

In contrast, Keynes was famously frugal in his private life, hosting parties where there was not enough for the guests to eat, according to no less a witness than the writer Virginia Woolf. Churchill was a lavish host at his country estate, Chartwell, which he struggled to maintain financially.

Churchill lost big in the Great Crash of 1929 and the losses were made on borrowed funds.

In common with Keynes, Churchill was sobered by these dramatic losses and in the early 1930s he aimed to change his style and start analysing listed companies as a value investor.

In 1931 as the infamous “sucker rallies” gripped Wall Street, Churchill re-entered the fray. As Lough explains: “The new investment policy lasted a month before he abandoned it — he then bought and sold Western Union shares four times in a fortnight.”

By 1932 Churchill’s writing and public speaking meant he remained one of Britain’s top income earners — he made £15,000 in 1932. “The problem was that his spending during the year had reached £30,000, including £6000 needed to cover investment losses.”

And on it went.

Years later Churchill’s widow, Clementine, had to sell a set of his paintings to maintain her lifestyle.

In contrast, Keynes left a fortune worth more than $30m in today’s dollars.

Investing with Keynes, by Justyn Walsh, will be released on March 30 by Black Inc. No More Champagne (Churchill and His Money), by David Lough, is published by Picador.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout