Helen Coonan on restoring her image as the chairman who stayed the course at Crown Resorts

The former Crown Resorts chairman says the record should reflect she stayed the course to line the casino giant up for success. But her former colleagues are divided on her image restoration plans.

Helen Coonan has requested this interview. She has also chosen a table she thinks best to conduct it over lunch, and might even choose what everyone eats if given half a chance.

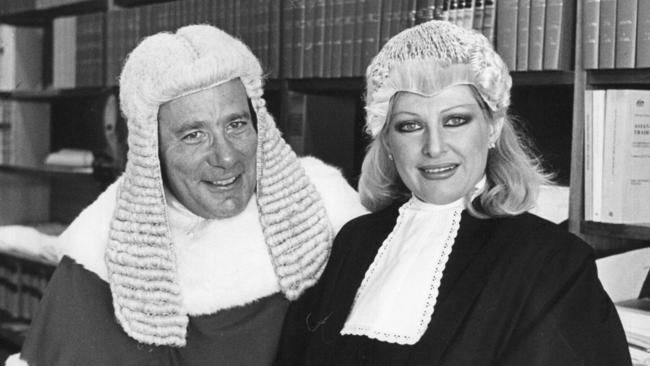

The 74-year old blonde with a professional bouncy blow-dry, a colourful beaded Camilla top, and a sharp blue pantsuit is clearly used to calling the shots.

She is decidedly unused to the lingering questions that remains from a decade on the board of Crown Resorts, the James Packer-controlled casino operator that nearly blew itself up under a cloud of money laundering, tax evasion and infiltration by organised crime.

Coonan is now on a mission to restore her brand.

“I paid my dues,” says Coonan as the John Dory arrives. “The easiest thing for me to do would have been to walk away and not take on the whole remediation of Crown, which was a super serious experience, but I had the courage of my convictions.”

Coonan stepped up from non-executive director of Crown – a role she had held for eight years – to executive chairman in 2021 after several members of the board resigned and executives stood aside amid the money laundering controversy.

It’s this work that she did – steering the gaming giant through three separate state inquiries, the Covid-19 pandemic, border closures, the construction of Crown’s Sydney casino, and handling three separate takeover proposals – that she wants to be known for.

“Nobody remembers who the individuals are out there, day after day, trying to bail water out of a difficult vessel,” she says of Crown.

“I’m really, really glad I did it. It was a bigger purpose than just me and I’m really glad that it landed in a good place.”

That good place was the exit of Packer and other shareholders via a $8.9bn takeover by private equity group Blackstone; and the opening this week – after two years of licensing and regulatory delays – of Crown’s Sydney gaming floor.

Now, through this interview, she wants to pivot the public’s view back to her being the saviour, rather than one of many at Crown who were asleep at the wheel.

It’s a complicated ask from a complicated person.

This is a woman who parlayed her legal nous as a barrister to become a Beauty and the Beast star-turned communications minister. She married a judge, owns several race horses, and doesn’t gamble. And she took home $700,000 per year as the executive chairman of Australia’s biggest casino operator.

Much of the feedback on Coonan is extremely positive.

John Howard says he “enjoyed” working with Coonan, who served in his cabinet from 2004 to 2007. “She always sought practical solutions and on several important issues developed innovative ways of tackling problems. Her personal and professional ethics were of the highest order,” the former prime minister says.

John Berrill, a lawyer who was part of the founding task-force of the Australian Financial Complaints Authority – which Coonan chaired from 2018 to 2021 – found her work over a difficult transition period to be very good.

“She did a very good job,” says Berrill. “There was a lot that could have gone wrong.”

But those who served with her at Crown say she is delusional to think that after a decade on the board she can just “rewrite history.”

“It’s about being revisionist and that’s just bullshit,” says one of the six unnamed former Crown board members spoken to for this piece. “To try to make yourself Teflon is just amazing. Being on the board as long as she was, makes her part of the problem.”

She, was after all, on the Crown board during the years when organised criminals bought in shopping bags of cash to be laundered on the gaming floor; some $61m of tax was dodged in Victoria; and in 2016 when 19 people from Crown’s China operations were arrested for illegally promoting their casinos.

That happened, she says, because the board was kept in the dark by select highly-regarded senior managers.

The Crown board simply did not know to even ask about what they didn’t know existed, she says.

“This was a board where information was withheld by senior management on material matters – and you can’t know what you don’t know,” Coonan adds.

Some former directors think that as chair of the audit committee she should have been well placed to see money trails that led to nowhere, although they are also quick to point out that no actual money laundering charges have been laid anywhere in relation to Crown.

“I liked Helen and think she did a good job but she was no less suspecting than anyone else on the board,” says another unnamed director.

Other views on Coonan by Crown directors who overlapped with her vary from being too focused on Sydney “at a time when they needed more Melbourne folk on the board” to “at the very best you come out of this neutral”.

One director who is more effusive is Ziggy Switkowski, who was chief executive of Telstra when Coonan was communications minister, and who sat with her on the Crown board for two months at the end of her tenure. He says she was “good to deal with, both practical and commercial”.

Switkowski took over the Crown chair from Coonan and describes her role during multiple royal commissions and inquiries into the company as “one of the most demanding roles in the country at that time.”

“She is a details person, a hard worker, pretty decisive and I do trust her,” says Switkowski.

Would he personally consider her for a board role given she was on the board when things went wrong?

“She would make an excellent board member,” Switkowski says, though he adds: “I don’t know if that means forgiven. I would have to be mindful of other considerations that others would make on reputational considerations. If it was just left to informed judges, then they would consider her.”

Her naysayers also bring up her use of personal connections, of which she has many.

Packer’s father Kerry went to school with Coonan’s husband, former Supreme Court judge Andrew Rogers, at Sydney’s exclusive Cranbrook and Coonan tells me she considered herself a friend of James’s mother Ros.

In the Senate, she employed Gladys Berejiklian before she entered NSW politics and eventually rose to premier.

Some former board members say she used to boast of strong relationship with the then premier but noted Berejiklian never seemed to take her calls.

Coonan denies this. She does know Berejiklian, who worked for her when she first became a senator, but says she never called on her on Crown matters and nor did she ever claim to.

Berejiklian declined to comment, and would only say she did not take any calls in relation to Crown when she was premier.

Then there is the rumoured connection between Coonan and her husband and Patricia Bergin SC, the former Supreme Court judge who chaired the NSW inquiry into money laundering at Crown, and NSW gaming authority chairman Philip Crawford.

Again no, says Coonan. Despite talk of cakes in the Southern Highlands and coffees in the Blue Mountains, Coonan says she and her husband have never dined with either of the two and neither of them have worked with either Bergin or Crawford, nor have either of their spouses.

It’s fortunate she is so clear, because Crawford’s praise is strong enough to raise a sceptic’s eyebrow.

“I’m a bit of a fan,” says Crawford. “I knew her when she was a solicitor and barrister.”

Crawford says she “impressed” him throughout his dealings with the gaming group after the release of the Bergin report.

“She understood the need to replace key employees. Crown was going to have to blow itself up to save itself. The inquiry uncovered a lot of bad behaviour and there weren’t many left in the cupboard we could work with,” he says.

And Bergin wrote of Coonan in her report: “Her character, honesty and integrity had not been and could not be called into question”.

This was a stark contrast to the Victorian royal commission, chaired by former Federal Court judge Ray Finkelstein, who did not spare the board when he concluded: “Wherever I look I see not just bad conduct but illegal conduct, improper conduct, unacceptable conduct and it permeates the whole organisation.”

Coonan puts that stark difference down to the timeline. Victoria followed NSW and had to find new ground, she says.

Even her defenders say with the benefit of hindsight the Crown board should have done more to know they had the right information coming in.

“All of the directors should have had their eyes closer to the business,” says Crawford. “The board was not apprised of certain conduct, but people in any industry need to keep digging to make sure the story they are getting is true and correct.”

Switkowski says that while having regulatory governance as an unambiguous priority is a modern phenomenon, the board undoubtedly “fell short”. “The priority was financial returns and running a good business and absent complying with regulations,” he says.

Coonan, however, believes Crown could have failed without her.

“I don’t think Crown would have survived unless I had been there to stand out in the rain and get it sorted … I did feel that I had to step up and be counted or else people would have lost their jobs,” she says.

“There may have even had to find some kind of administrator or receiver and it would have been terrible for the business and for shareholders.”

A sense of injustice is one reason Coonan wants to speak publicly now. She points to Australia’s major banks as examples of where more significant corporate crimes have occurred and yet non-retirement age board members have emerged relatively unscathed. In the past few years Westpac has paid a record penalty of $1.3bn to settle legal action over money laundering and child exploitation allegations, and Commonwealth Bank admitted to charging dead people superannuation advice fees.

Coonan isn’t lacking work. She sits on the advisory board at JP Morgan and is involved in SimpleKYC, an on-boarding verification software promoted on its website by former prime minister Scott Morrison and used by the banks – and currently under consideration in the gaming sector.

“She is clearly still very competitive and ambitious,” says one former Crown board member supportive of Coonan.

So is this interview about getting back into the board room of a major company once more?

Coonan is coy. “That would just depend on the role,” she says, standing up to greet friends at another table. And with that, lunch is over.