In a presentation to the Australia China Relations Institute at Sydney’s UTS, this week Opposition trade spokesman and NSW cattle farmer Kevin Hogan made it clear that he planned to continue this tradition if indeed he ever becomes trade minister.

He talked of the “economic miracle” that was the massive expansion of global trade over the past 20 years from $US3.5 trillion to $US30 trillion which, he argued, had been a factor in bringing more than a billion people out of poverty – including several hundred million in China.

“I always say to social welfare advocates that if you want people’s lives to improve and you want people to be more prosperous, you should all be trade advocates,” he said.

In striking contrast to some of the rhetoric of the former Morrison government – and potentially some of his political colleagues – Hogan made it clear that he thought Australia’s $200bn-plus trading relationship with China was a good thing.

In an hour of conversation, Hogan talked of the importance of global trade in general in lifting millions of people around the world out of poverty and said that it was a good thing that Australia’s trading relationship with China had continued strongly – despite China’s specific sanctions (official and unofficial) on $20bn of exports – in the face of political tensions.

Hogan avoided taking pot shots at the Albanese government, instead taking the opportunity to present himself to his audience as a potential future trade minister who would be passionate about his job and one who would not shy away from the importance of trade with China.

As he said, the trade portfolio in government was probably the portfolio which was the most bipartisan as both sides of politics wanted more success for Australian exporters, more free trade agreements and supported the World Trade Organisation process.

A federal election is potentially a year away and the Opposition’s policies will come under closer scrutiny.

Asked to articulate how his side’s trade policies might differ from the governments, Hogan said it was the Coalition side of politics which had always been the traditional supporter of free trade while Labor’s supporters in the union movement traditionally had problems with it.

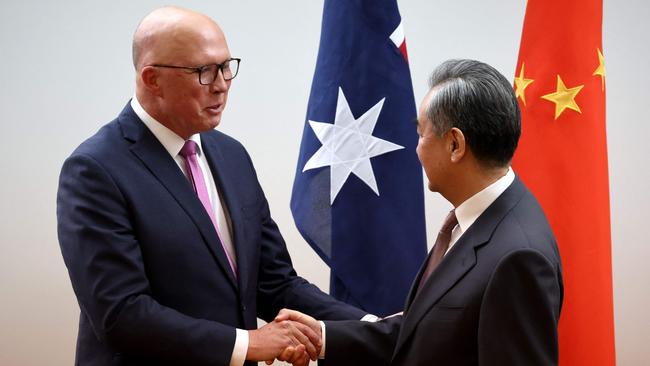

Hogan, who was one of the federal politicians who met with Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi during his recent visit to Australia, talked of the importance of countries which had disagreements with each other keeping them behind closed doors if possible – an interesting point given that it was the outspoken comments of the former Coalition government which prompted the Chinese to put trade sanctions on Australian exports such as barley, wine, beef and lobster.

Much has happened since those days, and the Coalition side of politics has grappled with its world view now that the Morrison era is well and truly over.

Lessons have been learned by the Coalition from the last election, including the potential danger of untrammelled dog whistle anti-China rhetoric to fuel racism which could cost votes with the Chinese-Australian community – many of whom have traditionally been conservative voters.

China itself has also changed, with the realisation that the days of “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy (of which Wang Yi was one of the architects) wasn’t working and ultimately was not in China’s interests.

Hence the different approach from China’s ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian, who arrived in Canberra just over two years ago with a clear goal of improving relationships – and even from Wang Yi himself during his visit.

There have also been a string of recent meetings between Chinese leaders and senior members of the US Biden administration.

Hogan avoided the path of other politicians lecturing Australian exporters to argue for the importance of trade diversification in the wake of the tensions with China, recognising that while not having eggs all in the same basket is important, trade will go where it works and makes sense.

The idea that Australia could sell, say, as much iron ore, coal, LNG, and agricultural goods to other countries as it has been able to do with China is glib.

That said, he did acknowledge that Australia had found itself in a “weird” position where the country which was by far its greatest trading partner (trade with China is more than that with Australia’s next five trading partners combined) was also one seen as potentially one of its greatest security threats.

“This is quite uncharted territory for us,” he acknowledged.

“It is good for the benefit of Australia that we have a great trading relationship with China which is a result of our complementarity.

“But if we were in a national security forum some of the people would say that China was our biggest national security threat.”

Australia is not the only country to have China as its largest trading partner despite ongoing political differences.

European countries such as France, Germany and Italy have had a strong relationship with China but now find President Xi Jinping’s support for Russian President Vladimir Putin a serious problem.

Managing “weird” – the security implications of a rising China with the economic potential of trade – but also the potentially positive security aspects of maintaining trade ties with the world’s second largest economy is one of the challenges which will be faced whichever party is in power in Canberra for decades to come.

Hogan, who prides himself on being pragmatist, seems to be taking a different tone to some of his former and even current colleagues.

But as he says, the debate in the trade sector is very different to the debate in the security sector.

Does that mean the Coalition’s approach to handling its ties with China has changed?

It is hard to tell but the Coalition of 2024 and 2025 will have to walk a fine line between both issues – taking a potentially more nuanced approach with China while its policies come under more scrutiny as the election comes closer.

In Australian political history, the National Party has always been one of the strongest advocates of global trade, given the importance of exports to the Australian farming community.