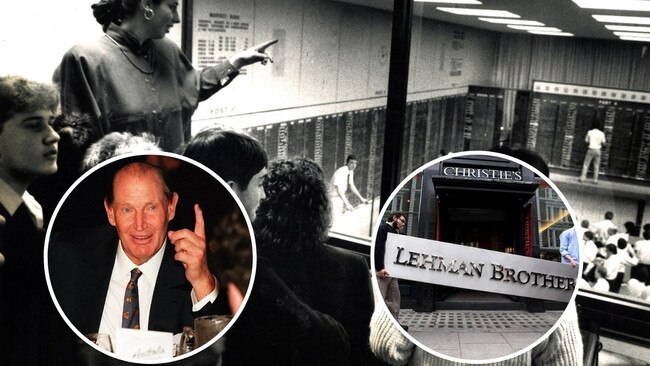

From glory days to banking busts

When we go back to 1964, we find a society which has many lessons for contemporary Australia. Robert Gottliebsen looks at events and watershed moments which shaped the business world.

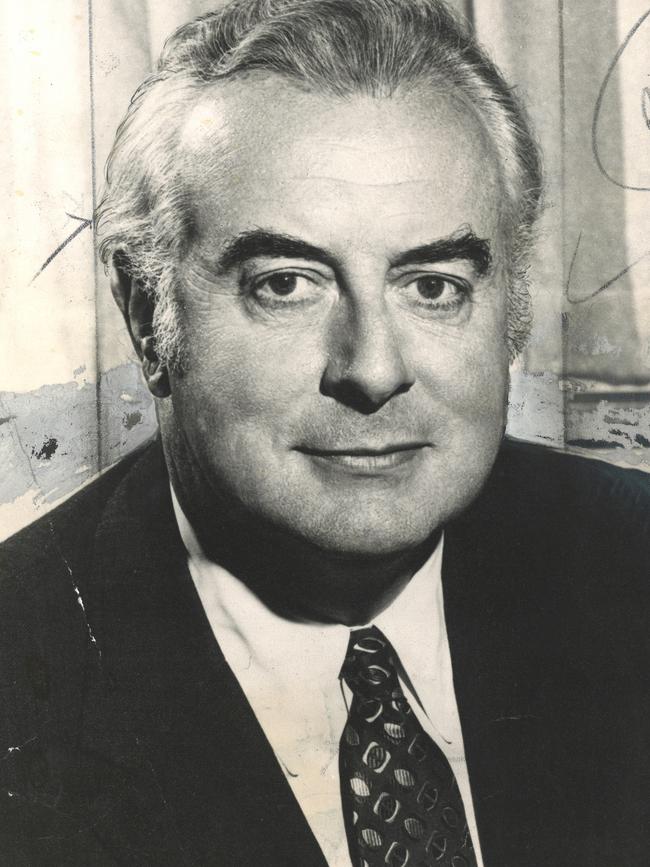

When we go back to 1964, we find a society that has many lessons for contemporary 2024 Australia. In many ways, when Gough Whitlam came to power in 1972, he began to swing away from the 1960s, but Anthony Albanese is swinging the nation back to 1964.

In 1964 I was a youthful 23, but I had been running the business newsdesk for the Sydney Morning Herald for two years. I was shifted back to the Melbourne office of the Australian Financial Review (my hometown) because, as a prelude to its launch, The Australian had recruited all but one of the Melbourne AFR journalists.

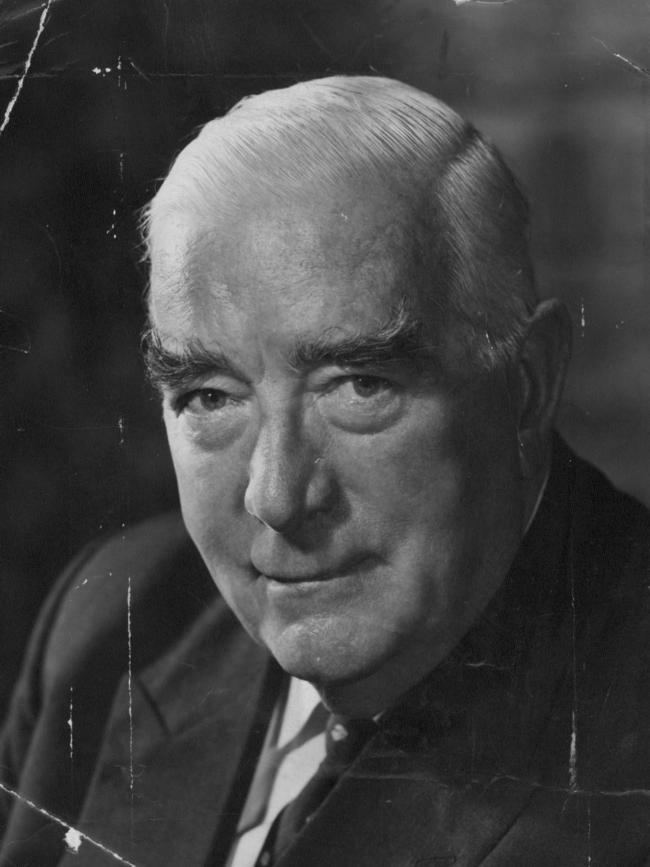

In the six decades that followed, both publications prospered but back in 1964, most attention was being directed towards the repercussions of the November 1960 mini budget delivered by then treasurer Harold Holt, which smashed the stock market.

The 1950s had been a great for many sectors, including retailers. It was a time when banks were regulated, and many retail/property empires were expanded financed on direct borrowings from small investors looking for higher rates.

The Holt measures and the subsequent share market collapse dried up investor loans and triggered a large number of crashes led by Reid Murray, the Korman Group and Cox Brothers.

Looking back over the last six decades, Australia has been hit with a series of stock market crashes, including November 1960; the mining crash of the 1969-70; the 1987 crash; and the global financial crisis in 2008 to name just a few. But after each crash, Australian markets recovered, and those who remained invested in strong stocks (or the index) recovered their losses and continued to make money. The ability of the Australian stock market to recover from crashes must be the biggest single lesson of the last 60 years.

In the early 1960s, there were moves being made that would transform the national business community in the six decades that were to follow: Frank Lowy and John Saunders started Westfield; variety store chain Coles purchased S.E. Dickins to launch into the supermarket business.

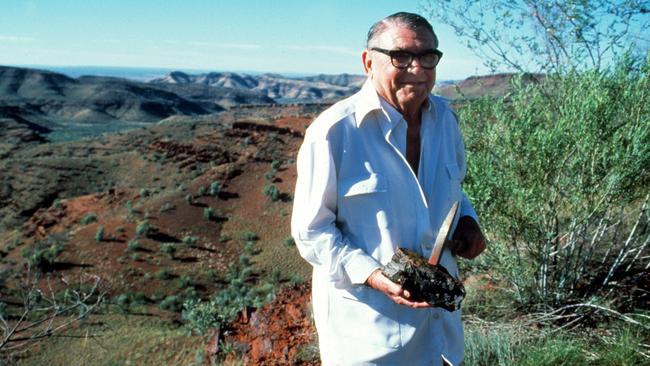

Secretly, in the 1950s, Lang Hancock and Stan Hilditch had made major iron ore finds in Western Australia at a time when BHP was adamant that Australian iron ore should be used for its Australian steel operation. Exports were banned.

The Hancock and Hilditch discoveries were the forerunners of Rio Tinto’s Hamersley Iron and BHP’s Mount Newman. By 1964, the government had relented and was allowing iron ore exports, which would provide enormous wealth to the nation for the next 60 years.

In the aftermath of World War II, Australia realised that its best form of defence was to have an extensive industrial base, and so manufacturing operations were established around the country, often protected by tariffs. Examples include the establishment of a vast automotive industry led by General Motors, and a plastics/explosives industry led by ICI (now Orica).

The Australian manufacturing industry was highly unionised and management control was often shared with union officials who had the right to be consulted over a wide array of decisions. The combination of these union rules and the lack of scale increased Australian manufacturing costs.

But the defence imperative meant there was widespread agreement that tariff and dumping protection was required.

Australia also had both a regulated currency and banking industry.

The long reign of Robert Menzies as Prime Minister ended in 1966, two years after the major iron ore export concession was granted, and one year after oil was discovered in Bass Strait by Esso-BHP.

The Australian population was expanding – also part of our defence policy – but much of the nation’s wealth was still produced by agriculture, led by wool. Few realised that the iron ore development in WA and oil and gas in Bass Strait and later elsewhere would transform the nation.

The Albanese government, like the Menzies government of the ’50s and ’60s, wants to restore Australian-made goods. The government also aims to restore the 1950s and 1960s union power via the industrial relations legislation, but without 1960s-style tariffs and the other protection measures, including currency setting and bank regulation.

As the Japanese war scars began to fade, the drive to make products in Australia began to decline, particularly as Japan emerged as our largest export customer via iron ore. When Gough Whitlam came into power in 1972, one of his first actions was to lower tariffs. Subsequent governments would reduce them further.

The Hancock-discovered Hamersley iron ore development was driven by what is now Rio Tinto, although in the ’60s it was the innovative Australian company CRA, and Rio Tinto was the major shareholder. The chief of CRA, Maurice Mawby, used his Japanese sales contracts as security for the borrowing necessary to construct the mine, railway and port. At the time such financing was rare.

The Hilditch deposits had a harder road. The giant US miner AMAX began the development but realised they would need Australian equity and partnered with CSR. But, as the cost of the Mount Newman mine and infrastructure escalated, BHP and Mitsui were bought in as partners.

Today we accept that it makes sense to dig up our minerals and send them to Japan or China for processing, but that was not the way Australian mining was conducted prior to the iron ore boom. Australian miners, whether they be at Mount Isa, Broken Hill or Whyalla, always aimed to process the minerals here in Australia, often to the metal stage. So, when Hamersley and Mount Newman and other iron ore miners approached the WA government to export, the state was anxious that pig iron and hopefully steel would be produced in WA.

But the iron ore miners argued that the cost of developing these mines was so high that the iron ore should be sent overseas, with minimum local processing. WA mining minister and later premier, Charles Court, however, was adamant there had to be a long-term commitment to producing pig iron or steel in WA.

As the iron ore exports began to rise sharply in the late 1960s, a dramatic event took place in Australian mining – Poseidon discovered nickel in WA. That sparked a speculative mining boom akin to the gold booms more than 100 years earlier.

But by the time Whitlam came to power, the boom had faded because Poseidon’s and many other discoveries had proved disappointing. Moreover, the Middle Eastern oil companies via their OPEC organisation had withheld oil and the price had risen fourfold.

The world entered a period of much greater inflation, which in Australia, was not helped by Whitlam government’s high spending. After the Whitlam government was dismissed there was a period of relative stability. Malcolm Fraser promised to tackle union control and make Australia more efficient – but he didn’t do it.

The high protection and government assistance resulted in the motor industry becoming much larger, and at one point, Australia had five leading motor makers: General Motors Holden, Ford, Chrysler, Nissan and Toyota. This was not sustainable.

The banking revolution

Meanwhile, in the 1970s, Australia was on the brink of a banking revolution that would bring major changes to the 1980s and 1990s. The Fraser government commissioned a report into banking headed by Keith Campbell, the former head of the Les Hooker’s property group. He recommended deregulation of the banking business sector. This would allow foreign banks to come to Australia.

The local banks saw danger and believed they needed to merge to prepare for a foreign invasion. The ANZ began having talks with the Commercial Bank of Australia, which is also based in Melbourne. The Bank of NSW didn’t want a major Melbourne-based bank threaten its position, so in 1981 it outbid the ANZ and acquired CBA. In the process, the historic Bank of NSW banking name was changed to Western Pacific Banking Corporation – Westpac.

In 1982, National Bank chief executive Jack Booth responded by buying and the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney. ANZ was the wallflower, and two years later acquired Grindlays Bank, which included the National Bank of India and operations through Asia. The ANZ planned to be Australia’s overseas bank but later ANZ boards stepped back from the ambitious aim and Grindlays was sold.

The locals did not want overseas banks taking their market share. So, in advance of the invasion and with deregulation, they began much more aggressive lending policies

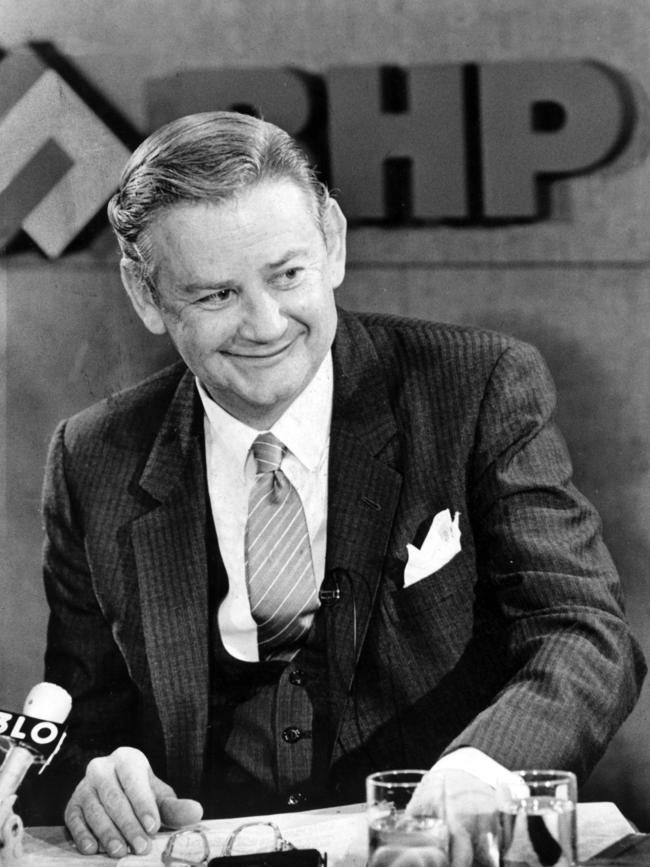

About 1982, Alan Bond was preparing the Australia II challenge for the America’s Cup, not realising the impact a win would have on Australian banking. In March of 1983, Bob Hawke became prime minister and Paul Keating his treasurer. Overseas banks were invited in.

Alan Bond’s stunning September 26, 1983, America’s Cup victory caused the American and other foreign banks to sit up and take notice of what was happening Down Under. Bond was the face of Australia and he was offered large loans by US banks which enabled him to pay top price for assets, including a string of breweries, the Nine Network from Kerry Packer, and major gold and gas investments.

Rise of the moguls

Earlier, Robert Holmes a Court almost purchased Ansett and was now aiming to buy BHP, while John Spalvins, who controlled Adelaide Steamship Company, began picking up a string of industrial companies.

While the entrepreneurs were gaining the headlines, both the local and overseas banks were also financing property purchases on a massive scale. Prices of commercial properties skyrocketed. The OPEC cartel was swamped by other producers and the oil price fell which provided another stimulation. That oil fall was also a tragedy for CSR, which had bought oil and coal assets before the slump. It had borrowed large sums and began selling mining assets to pay the banks.

One of the assets CSR sold in the 1980s was its stake in Mount Newman, giving BHP control and underwriting profits for the next 40 years. CSR concentrated its diversification on building products rather than iron ore. It was a fundamental mistake.

Meanwhile, inflation started to rise along with interest rates. In October of 1987, there was a 20 per cent fall on Wall Street. The crash crippled Holmes a Court, Spalvins and Bond.

Bond’s rescue attempt landed him in jail.

After the 1987 share market crash, property first fell but then started to rise again. Property people around the country didn’t realise that when the share market had a major fall, property normally followed, often after 18 months.

Australian interest rates rose to 17 per cent and the fall in the property market was massive. The Australian and overseas banking losses in 1990, 1991 and 1992 were hideous – and totalled more than $9bn or 2.25 per cent of GDP. Westpac and ANZ both went close to falling over.

Kerry Packer, who had sold his Nine Network to Bond for top dollar, saw the chance to control Westpac. Alongside him was the man who Packer envisaged would restructure Westpac – Al “Chainsaw” Dunlap. Chainsaw had gained his reputation from previous takeovers – he was ruthless in retrenchments and asset sales.

It looked like Westpac would become part of the Packer empire. Westpac appointed as chairman, the former chief executive of the Adelaide-based Simpson appliance group, John Uhrig. Most people (including the Packer camp) thought the combination of Chainsaw and Packer would brush the relatively unknown Uhrig aside, but Uhrig took the fight to Packer and Westpac did not become a part of the Packer organisation. Packer instead bought Nine back at a low price.

The ANZ struggled through. The State Bank of Victoria was in big trouble and Paul Keating arranged the sale to the Commonwealth Bank, which gave the government bank a huge deposit base. That deposit base propelled the Commonwealth Bank to become Australia’s most successful bank.

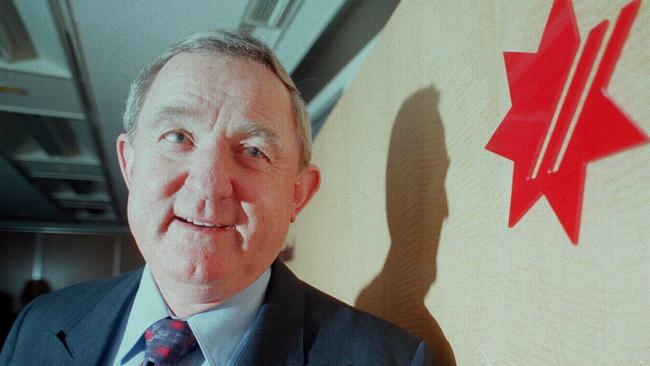

Meanwhile, Don Argus became chief executive of NAB and used the weakness in Westpac and ANZ to grab market share to become Australia’s largest business bank

After the 1987 crash, the federal government took two steps that would have a long-lasting impact. First it guaranteed depositors holding under $250,000, and in 1987 introduced franking credits to prevent the double taxation of profits.

The deposit guarantee gave a degree of certainty to bank deposits and provided public bank confidence which would become important in insulating Australia from the 2008 global financial crisis.

In addition, the banking capital rules made home loans the best way to gain a return on bank capital. Gradually, most banks increased the proportion of home lending in their books, and as a result, the price of housing rose to levels that could never have been envisaged in the 1960s and 1970s. The baby boomers who bought houses when they were in their twenties and thirties have made a fortune.

Selling off government assets

With Paul Keating as prime minister, two significant privatisations of government assets were launched.

The first was CSL, and the government didn’t understand the value of what it was selling. The shares were floated about $2.30 in 1994 after 33-year-old Brian McNamee had been recruited as chief executive by industry minister John Button.

McNamee had a vision to harness Australia’s ability to produce pharmaceutical products from white blood cells to create a global empire. After an initial small acquisition, CSL started its global adventure by acquiring the Swiss company ZLB. Then there were more acquisitions, and the company set up a massive white corpuscle collection operation in the US. CSL has been the most successful global empire started in Australia and is still based here.

After an earlier placement, the government floated Qantas in 1995 and at the time thought it was a much bigger deal than CSL. Qantas’ main rival was Ansett which had come out of the unsuccessful Holmes a Court raid to be owned by News Corp and TNT. The inner strength of Ansett was to later help both companies when they each faced financial pressure, at separate times.

TNT sold to Air New Zealand, and later News Corp arranged to sell to Singapore Airlines, but Air New Zealand used its presumptive right and took over Ansett.

However, when Air Zealand took full control of Ansett in 2000, it simply did not have the management talent or financial strength to run the company, and two years Ansett went into administration. If Ansett had survived, its rival, Virgin, would almost certainly have collapsed. The consequent Qantas market share rise masked the fact that, leaving aside its low-cost airline Jetstar, its costs were much higher than its overseas rivals and this was to become a major challenge in later decades.

Two years after Qantas, in 1997, the government floated Telstra. It should have been a massive growth operation given the telecommunication boom. But, like Qantas, it carried the burden of the high costs that had been established when it was a government organisation. It is only now that Telstra is starting to emerge with costs more appropriate to the industry that it is in.

Also in the 1990s, after BHP had beaten off Homes a Court and sorted out its shareholder structure, it looked around for expansion opportunities. It found three. BHP had a long-term commitment to produce iron in WA, so established an iron-making operation using natural gas.

Rio Tinto started a smaller scale plant. Both failed. BHP also extended into beach sands – another disaster. Finally, BHP wanted to obtain global dominance in copper from the mine to the metal, so it bought the US Magma operations. In 2008, all three ventures collapsed and BHP was looking at losses in excess of $9bn. In the top echelons of the company there was sheer panic as they feared they had destroyed BHP. But China was emerging as a much larger iron ore buyer which swamped the losses that BHP incurred.

But out of that crisis came a series of changes to BHP management, which resulted in the company becoming the lowest-cost producer of iron ore in Australia, its oil and steel interests to become dominated by iron ore exports. Shareholders made a lot of money from the exercise.

ASX market dominance

Around the turn of the century, when BHP was making its ill-fated expansion plans, Australia’s four major banks believed their strong position in the banking industry made the superannuation and wealth management sector and ideal one to enter. This would enable them to dominate both interest-bearing and equity markets in Australia but none of their banks had the management ability to realise the potential.

CBA and NAB made the biggest acquisitions: CBA bought Colonial after outbidding ANZ, while NAB bought MLC, which was then owned by Lendlease. NAB was so confident about the potential of MLC that it moved quickly to add AMP. AMP could have obtained a bid of $20 a share from the NAB, but it fought off the Melbourne-based banker with great vigour.

Like the other banks, NAB did not have the management ability to integrate the MLC, so it left the MLC to run separately. The MLC even banked with Westpac rather than NAB.

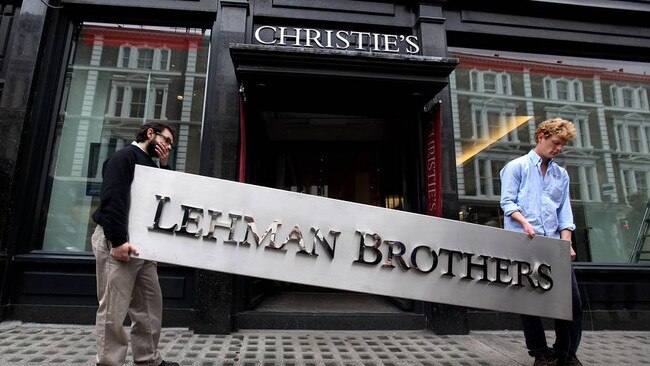

The 2008 global financial crisis started with deep problems in the US banking system. The strength of Australia’s banking system (the life office acquisition mistakes had not been recognised) plus the increased demand from China as it stimulated the economy meant Australia did not suffer like most other countries.

In December of 2013, 68 years after the surrender of Japan, General Motors announced it would stop making cars in Australia. It was the formal end to linking defence with an Australian manufacturing base that was a foundation government policy in 1964. A government subsidy had covered the cost of bad work practices and management control shared with unions. The government decided to stop the subsidy. GMH management desperately tried to convince the unions to agree to modern work practices. They finally succeeded, but it was too late and the deadline for work practice change set by Detroit had passed.

By 2013, we had forgotten the lesson of World War II. The decline in industry stocks left the ASX dominated by banking, followed by mining.

Australia now faces a dangerous regional environment without a manufacturing base.

Again in 2013, NAB sent one of its best executives in Andrew Hagger into MLC to find out what was going on. He discovered a rat’s nest of problems. Hagger thought he could fix them, instead Hagger and the NAB chief executive Andrew Thorburn became their victims.

As in BHP, the subsequent NAB management revolution that followed a disaster made it a much stronger bank. NAB disposed of its UK banking interests as well as the MLC. The other banks have also exited wealth management

After 60 years of massive change, Australian companies now face a new era of change. The industrial relations legislation means that as in the 1960s, management control will again be shared with the unions. Mining costs will rise sharply. Government-funded organisations are becoming the major employers of labour, which can hinder motivation for productivity. The US is imposing tariffs which could spread protectionism around the world, but at the same time, artificial intelligence offers the prospect of a total new era of productivity.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout