It’s an odd thing that unelected central bank officials should be granted such economic power in a democratic system but independence is nonetheless viewed internationally as best practice.

In Australia’s case, it has helped to deliver sustainable economic growth, higher living standards and job creation.

And for those in Canberra who no doubt harboured some reservations about handing power to the RBA, there was some solace that if interest rates soared again, blame could be directed at the central bank.

Equally, if interest rates fell, the Treasurer of the day could quickly step out from the shadows to claim credit.

Politically, it was a win-win.

Interest rates have been a hotly debated topic in Australia for decades after they smashed the economy in the early 1990s to trigger a deep recession.

The rate debate formed the backdrop to current moves by Treasurer Jim Chalmers to reform the RBA by introducing a dual-board system, with one for setting interest rates, and the other focused on running the central bank.

After an independent review, it was determined that the interest-rate-setting board would include six external monetary policy experts, ostensibly to improve policy discussions.

On paper, it looks marvellous as the RBA gets to hear from a wider range of expert voices.

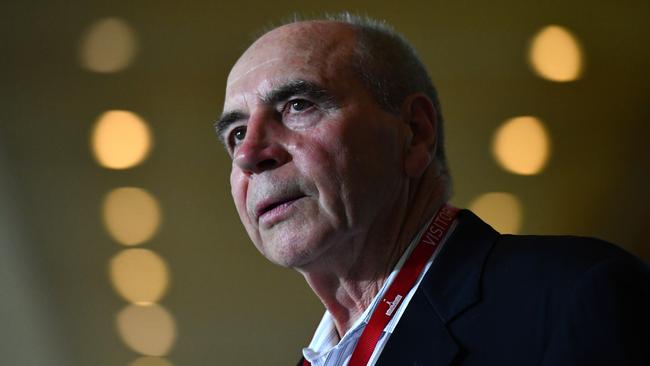

But that warm glow has been diminished by comments from former RBA governor and Treasury secretary Bernie Fraser, who said the ideas for change were “bullshit”.

Fraser said the new board would put the power to set interest rates into the hands of a special committee of “super nerds”.

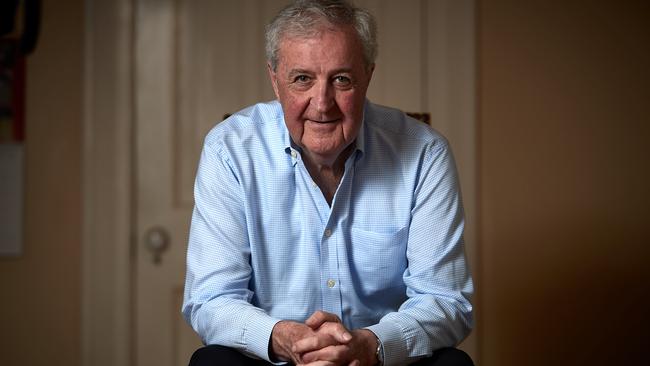

Fraser’s successor at the RBA, Ian Macfarlane, has been less colourful in his use of language but has essentially said the same thing, arguing that the balance of power around the board table would rest with outsiders, and not governors and their staff.

Australia would have the only central bank in the world with a decision-making structure like that, Macfarlane has warned, saying it would put a lot of faith in part-timers that are yet to be named.

Philip Lowe, who preceded the current RBA Governor Michele Bullock, was reluctant to welcome the changes, telling reporters they were an improvement only “at the margin.”

The reluctance of a string of RBA chiefs to endorse the changes should ring alarm bells and prompt a review.

What’s rarely been said about the plans for change is that they would undermine the RBA governor, as the six external experts could dominate public debate, taking the focus off those running the central bank.

The views of the governor, who represents an army of policy experts already within the bank, could get lost in froth of media headlines. That could detract from the certainty that financial markets, businesses and home buyers need.

Although the RBA is supposed to be apolitical, it does have an impact on politics, especially given the long history of tension between RBA governors and Treasurers, who are often at odds over policy settings.

Governor Glenn Stevens heroically raised interest rates a month before the 2007 election that saw treasurer Peter Costello punted from office.

One could see why muffling the words of an RBA governor in the day-to-day debate appeals to Canberra.

dow jones newswires

Moves to enshrine the Reserve Bank’s independence in the 1990s were viewed as a big step forward for economic management as it freed central bankers from political influence and focused them on quashing inflation.