For years McDonald’s was one of a handful of bedrock stocks that helped propel Douglass’s Magellan to more than $110bn in funds under management. Last year the burger giant represented 4.5 per cent Magellan’s global fund but has now slipped out of the top 10. Shares in New York-listed McDonald’s have rallied more than 15 per cent in the past financial year, suggesting the fund manager has been trying to stay off the fries by offloading its holdings.

This shows Magellan’s tastes are changing along with its management shake-up. These days Magellan under new CEO David George is a much smaller fund manager, with assets under management dipping below $40bn. It follows a volatile year where Douglass resigned as chairman and chief investment officer, sparking a broader shake-up.

The changes are out of necessity with the open class Magellan Global Fund remaining under pressure. It returned 20.6 per cent last financial year, latest figures show. This underperformed its benchmark MSCI World index by 1.8 per cent. On a three-year return the underperformance blows out to minus 7.8 per cent. The fund had a good June quarter delivering 7.8 per cent, coming in slightly ahead of the benchmark.

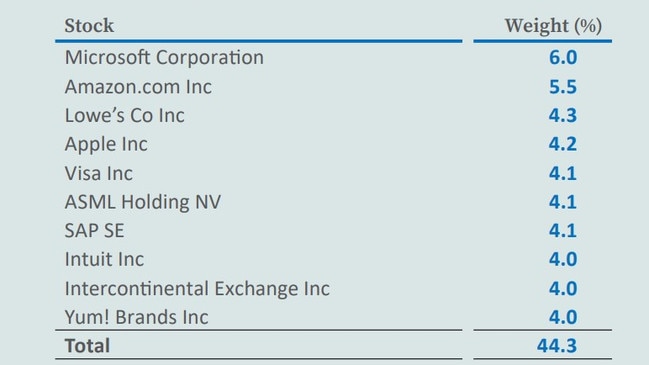

Software major Microsoft still retains top position in Magellan’s portfolio, although it too has been pared back. Microsoft’s weighting at the end of June was 6 per cent, versus 7.8 per cent a year ago. Tech company rallied more than 30 per cent in a year.

The biggest change is the sudden addition of Amazon as the second biggest holding at 5.5 per cent, while tech giant Apple is brand new to the portfolio and is now Magellan’s fourth biggest holding at 4.1 per cent. Both tech companies give Magellan exposure to businesses with strong cashflows and potential opportunities from generative AI. However, Google owner Alphabet has also been dumped from its long-held third spot, replaced by old world stock, the US hardware giant Lowes, which is new to the top 10 holdings.

Other stocks to move around include adding to an existing holding in Netflix (another former favourite of Douglass) on the back of new ad-based revenue and the password-sharing clampdown. Even with the buying Netflix remains out of the top 10.

Elsewhere Facebook owner Meta has been dumped from the portfolio. Other exits include Proctor & Gamble, Lloyds and aviation software play Amadeus.

Magellan’s joint portfolio managers Arvid Streimann and Nikki Thomas said the global portfolio was being adjusted to plan for a period of economic weakness either in the next six months or next year.

EY’s mountain impasse

Mount Everest always represented an impossible challenge, but the peak was ultimately conquered by climbers. In the world of the big four global auditors, Everest remains metaphorically undefeated.

Project Everest was the working name of an ambitious plan by auditor EY to separate the global firm’s audit and consulting businesses. The break-up included the Australian business and would have been the biggest change in accounting industry since the collapse of Arthur Andersen two decades ago left four global firms.

Project Everest collapsed spectacularly in April after nearly two years of work. In essence, thousands of global partners were about to vote the move down, fearing a much diminished business. The firm’s US bosses led the revolt and this set the tone for EY partners around the world.

While the collapse is still raw inside EY, Project Everest has relevance in Australia, with a discussion in Canberra about splitting the consulting and auditing arms of the big four. Former ACCC boss Alan Fels this week pressed the issue, saying self-regulation and government oversight of the industry doesn’t work. In essence, Australia would be on its own in pushing for a regulated solution to a problem the market was unable to solve.

The initial push for EY’s Project Everest was led by the firm’s global chairman, Carmine Di Sibio. It aimed to tackle once and for all the lingering conflict of interest issues hanging over the accounting firms. This came to light in a spectacular way in Australia when a PwC consultant was found to have used confidential government tax policy information for the benefit of the firm’s global clients. EY has no links to the PwC scandal, but the breach has tainted the entire industry.

Appearing at a Senate committee that has been probing the government’s relationship with consultants, EY’s Australian and Oceania chief executive David Larocca offered a rare insight about the sudden demise of Everest.

“This was an incredibly complex transaction involving 13,000 partners across 75 countries. This transaction had never been attempted before, as it required agreement on a number of difficult issues,” Larocca said.

Because agreement could not be reached on the transaction “in its contemplated form”, Project Everest came to a halt.

Importantly for the Australian context: “We very quickly formed the view that an audit-only firm would not have enhanced audit quality. In fact it would detract from audit quality,” he said. EY’s partners formed the view that “multidisciplinary capability” is required to serve clients.

Part of this was because a range of specialised non-audit disciplines are now required to complete any one company’s audit, he said. This specialisation can range from tax policy, to cyber and sustainability issues and all this can now make up a third of the work in audits. This meant auditors were increasingly relying on their own specialists across the consulting business, Larocca said.

His comments follow Deloitte Australia boss Adam Powick this week telling the same committee that while not impossible, there was no intention of splitting or ring-fencing consulting from auditing in his business. Powick said the combination of auditing expertise and consulting were the services that his clients, both business and government, were demanding.

PwC split

Both auditing bosses agreed the rapid spin-out of PwC’s government consulting business into a stand-alone entity was a matter of survival for the tainted auditing firm that was rapidly seeing public sector work dry up. The business, now called Scyne Advisory, was sold for $1 to private equity.

EY’s Larocca on Tuesday went a step further to put a valuation on the new entity of $1bn, given its expertise and the contracts the partners are sitting on. If the new majority owner, the private equity play Allegro Funds, gets the execution on Scyne right, this could represent a substantial windfall.

On paper, the intent of Project Everest had been to unlock EY’s consulting arm so it could serve a wider range of clients, given rules designed to keep auditors independent by preventing them from performing consulting services for the same client.

The split would have provided the market with greater choice in selecting audit providers as well as the consulting space, Larocca added. Larocca said EY audited a number of the tech firms in Silicon Valley, potentially more than its rivals, and this meant it was very limited in what other services it could offer alongside them.

However, the structure proposed by EY was not the ultimate answer to solving conflicts inside the audit firms.

“Splitting firms is not the salve to stop independent breaches – it’s actually not engaging in independent breaches. And similarly, it’s not engaging in breaches of conflicts of interest,” the EY boss said.

Larocca said it was making sure “you have the tone from the top” with the right message to staff, as well as systems and processes in place, and if there was a breach then the right actions were taken.

The Senate committee is due to deliver its final report by the end of November.

Magellan’s McDiet

Blackmores buy

It didn’t take long for Blackmores shareholders to waive through Japanese beer giant Kirin’s $1.85bn takeover, giving their overwhelming backing for a proposed buyout.

In April Kirin offered $95 a share for the Australian vitamin maker, including a special dividend, up from a pre-deal price of $76. Nearly 97 per cent of shareholders backed the deal.

For Kirin the takeover is all about building out a health business into China as well as the fast-growing consumer class into Asia.

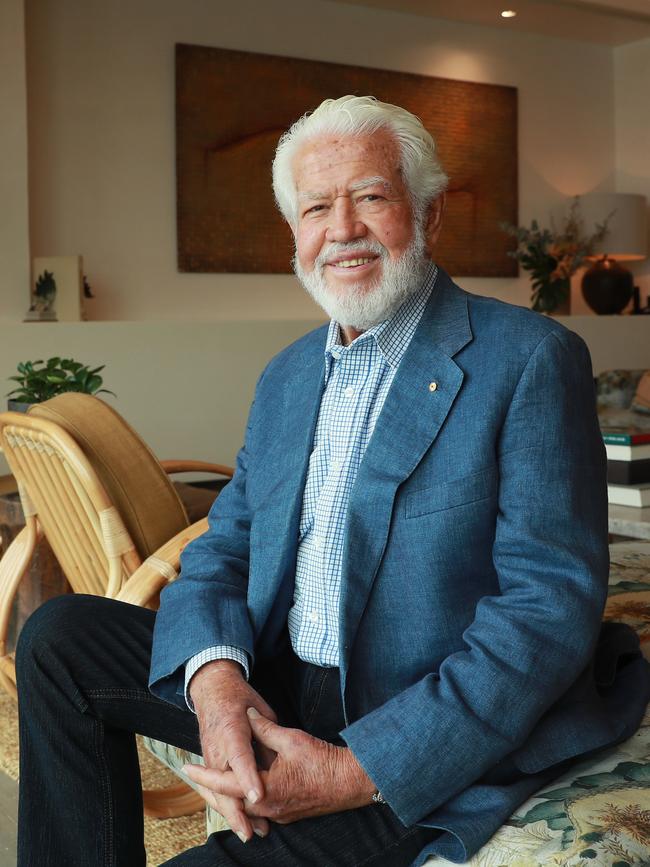

But the biggest development was a truce – of sorts – between former long-serving chairman Marcus Blackmore and the company that shares his name. Marcus controls 18 per cent and pledged to sell his stake to Kirin.

Marcus last year had a major falling out with the board under CEO Alastair Symington. In a big sign of thawing, new Blackmores chair Wendy Stops invited Marcus to address the meeting as part of the formal proceedings. There he acknowledged his previous criticism of the current board but added Stops was doing a good job. He also told shareholders he believed Kirin was a good custodian for the business going forward.

johnstone@theaustralian.com.au

It’s been a year of massive changes at the once-high flying fund manager Magellan but the starkest indication that Hamish Douglass is no longer in charge is that McDonald’s is out of favour.