‘We weren’t giving up’: ANZ walks new road into Asia

After years of pulling apart ANZ’s much-maligned international franchise, Shayne Elliott is quietly rebuilding a new pan-Asian bank. But this time he’s doing it his way.

It’s a warm, humid evening in Hanoi and Shayne Elliott is holding court among central bankers, politicians and diplomats.

Along the walls of the historic Metropole hotel – the same venue where US president Donald Trump and North Korea leader Kim Jong-un met nearly five years ago – are arrangements of perfumed floral wreaths sent to the Australian bank as gifts from customers from around the country. The celebration is to mark three decades since ANZ cautiously opened a single branch in the Asian outpost just a few blocks from the Metropole. But the presence of the Australian bank’s chief executive in the Vietnamese capital last week represents something more.

After years of undertaking the agonising process of pulling apart and selling off ANZ’s much-maligned international franchise, Elliott is again quietly rebuilding a new pan-Asian bank. But this time, Elliott is doing it his way.

On January 1, Elliott marks eight years in the job as chief executive with ANZ, and he is just warming up. He remains as determined as ever to seal the acquisition of Suncorp’s bank, which has been snared on competition issues. He’s also keen to get his entire retail bank on the long-promised new in-house tech platform, ANZ Plus. And after decades of heartache and pain in Asia, the pieces are finally starting to fall into place.

While most CEOs define themselves on acquisitions, Elliott’s tenure has been all about exits. That’s even with the $4.9bn Suncorp banking buyout still on the horizon. Since taking charge in 2016 it’s been a rapid-fire series of sales, pulling apart the “Super Regional” banking strategy painstakingly pursued over nearly two decades by his predecessors.

In all, Elliott has done more than 20 sales of joint ventures, holdings and investments across Asia, marking a rapid retreat from retail banking from markets including The Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Cambodia, Hong Kong, China and even Vietnam. But Elliott says it wasn’t a retreat from Asia. It was the wrong strategy.

The reason for the sales is that ANZ was sub-scale, he says. It was the fourth-biggest bank in Australia competing on the world stage against the likes of international giants Citigroup, HSBC and pan-Asian experts DBS and Standard Chartered.

“Our diversification in the past hasn’t been a positive. It’s been a drag. It’s been a negative,” Elliott tells The Australian in an interview in Saigon.

“We were never going to do anything.

“Actually what was happening was we were ending up being the risky part of the business.”

The higher risk meant the bank was forced to set aside more capital and this meant in most cases the Asian banking business – home loans, credit cards and small business lending – was earning less than ANZ’s cost of capital. Its large footprint was adding complexity to the business and becoming a massive management distraction, while returns were being weighed down at home. Investors hated it and marked down the bank for its international folly.

ANZ today is in 29 countries, mostly across Asia, and has a handful of priority countries: India, China, Japan, Singapore and Vietnam. And it’s all about the less glamorous space of moving money around for big business in payments platforms, transaction services, forex and financing their trade. There is as little balance sheet as possible.

Elliott says ANZ is in the business of helping multinationals move goods and capital around the fastest-growing region on the planet. He provides all the banking services for big companies to sell products to one another.

“That’s what we do. And we have 6300 customers only. We know who they are. We like all of them. They’re all the world’s best companies,” he says.

“Our strategy isn’t to add more customers, it’s actually to go deep with existing customers, countries and more services. And that’s what we do.”

Elliott says this was a matter of stripping ANZ back to its very core. And it involved simply getting a map out nearly eight years ago and following the flow of goods and money.

“We literally just drew a line: iron ore goes from Australia to China; car parts go from The Philippines to Japan. Silicon chips go from here to there. We need to be in each one of those end points. And that’s where we are. So every one of the countries we’re in is because they are a destination, or a sender of goods and capital into the region.

“And then secondly, we said the only way to make money on institutional banking is to lend as little as possible and do as much of all the other stuff like payments. Lending is capital-intensive, very, very low return and risky.”

While ANZ is barely known by most on the streets of Singapore, India, Thailand and even Vietnam, the Australian bank is big among the clients that count.

Names like Toyota, Volkswagen, Apple and Samsung across the region work closely with the bank. In Vietnam ANZ also banks low-profile Australian names like logistics major Linfox and rice exporter SunRice.

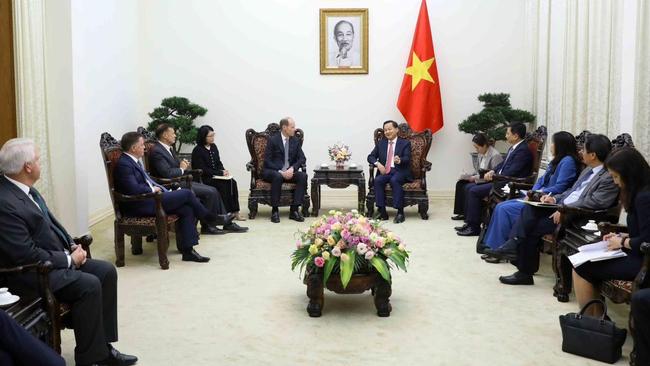

It’s Elliott’s first visit to the country in five years, and he has spent the past week meeting with customers, officials and politicians, including the country’s powerful Deputy Prime Minister Le Minh Khai in Hanoi.

In Vietnam, the lender is based in the capital Hanoi, as well as the finance hub of Ho Chi Minh City, also known as Saigon.

Apart from Macquarie, ANZ is the only other Australian bank in the country and is just one of a small handful of Australian names operating there.

This is a country with a population of 100 million and an economy slated to be among the fastest-growing in the world for years to come. It is expected to deliver 6 per cent growth for the rest of this decade. Vietnam is a big beneficiary of the “China-plus-one” manufacturing policy, as Western companies look to diversify their supply chains.

Once seen as a low-cost factory to make the world’s clothes and shoes, Vietnam is now rapidly moving up the value chain.

Samsung has invested billions to build smartphone manufacturing operations and Apple AirPods are manufactured there. The country has big plans to become a regional hub for EV makers and export markets. Add into this, the country’s own middle class is rapidly growing.

Elliott says the notion of China-plus-one had been around well before the Covid pandemic closed off supply chains. However, it was the pandemic that accelerated this thinking across the corporate world.

“Places like Vietnam had been massive beneficiaries of that. Because you look around and go, where else has a young, well-educated, technical workforce, relatively easy to come and do business?

“This is a big manufacturing powerhouse. And we help customers move goods and money around the region.”

Even so, ANZ’s Asian business, which is headquartered in Singapore and reports to institutional boss Mark Whelan, is yet to really hit the radar of Australian investors. However, last week, UBS analyst John Storey took a step forward, publishing a note saying ANZ offered a positive “diversification” from its Australian rivals in its offering of banking and payment infrastructure to big clients across Asia.

Elliott quips that just combing through ANZ’s annual results, where the bank posted a headline record $7.4bn profit and record revenue, the focus remains squarely on Australian mortgages. Commonwealth Bank last month sold its Indonesian bank, while National Australia Bank has been trimming back its Hong Kong business. Westpac has been seeking to exit the Pacific.

“We go and speak to investors and 98 per cent of the conversation with investors about Australian home loans, which is 20 per cent of our business. OK, I get it’s really important. It’s 20 per cent of ANZ, but can we talk about the other 80 per cent which is actually where this value is coming from?” he says.

“But to be fair, our diversification in the past was low-return. It was risky. Now we’re trying to retell our story and say. The business of today is different.”

ANZ’s international operations are now the fastest-growing part of the bank. Last financial year, Asia more than doubled cash profit to $1.15bn, according to financial disclosures.

Elliott says that when he took charge eight years ago, the easy path would have been to throw it all in and just focus on selling home loans in the bank’s home market of Australia and New Zealand, competing against the likes of Commonwealth Bank or Westpac.

“The core business model of international banking has been questioned – and it’s only gotten harder,” he says.

“And when you go and look at the numbers and once you look at all the world’s big banks and ask, who’s done the best for shareholders over a long period of time, there’s one common trait: mostly domestic banks have done better.

“And the reason is as soon as you start having international, you get this geometric increase in complexity and risk.

“But for ANZ, it’s who and what we are. So we decided before we gave up, we’d give it a really good shot at making it work.

“And that’s why I’m proud of what we’ve achieved.”

The author travelled to Vietnam as a guest of ANZ.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout