Revealed: The frantic days that followed AMP’s fall from grace

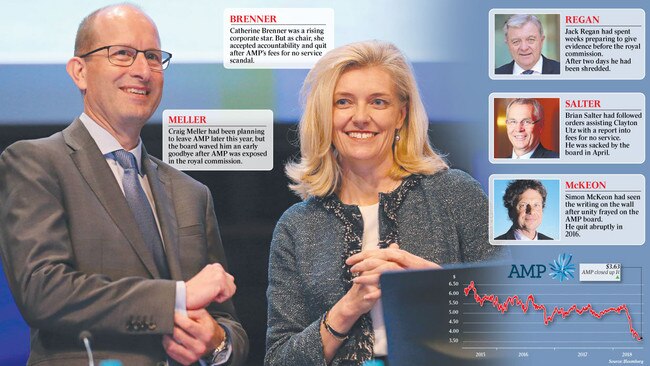

AMP’s greatest crisis hit when chairwoman Catherine Brenner was in Tokyo on holiday.

Catherine Brenner was in Tokyo watching the live stream of proceedings of the banking royal commission 8000km away in Melbourne’s Federal Court.

Brenner had been on holidays but was now in a hotel with a laptop, focused intently not on the snowfields near the Japanese capital but on the slippery slopes of AMP.

As Brenner watched, the reputation of the insurance giant where she had been chairwoman for almost two years was publicly shredded. Brenner’s career at AMP would soon be eviscerated as well, although she may not have realised it at the time. It was Tuesday, April 17. The dawn hours in Tokyo had given way to a cool early morning of 11C and a warmer day, a bit below average.

In Melbourne, it was also 11C. In courtroom 4A, commissioner Kenneth Madison Hayne QC had started day 12 of his royal commission into misconduct in the banking industry at 9.49am with an apology for being four minutes late.

“It’s not only retailers that have IT issues,” he said, tartly.

“Mr Regan, could you come back into the witness box please.”

It was Jack Regan’s second day giving evidence. He was the head of AMP’s advice business, a division housing the company’s financial planning money-spinner. Regan had been in the job just over a year but he was a 20-year AMP veteran.

The day before, Monday, April 16, had concluded at 4.10pm with Regan — sounding defeated — conceding that the commission had uncovered by that point 10 false or misleading statements made by AMP to the corporate regulator, the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. “And again, you agree that was misleading?” Regan was asked. “Yes,” he had again replied. By the next day Regan would lose count altogether.

By the end of day one, he was so knocked around by the experience that the legal team decided he needed the night off from further prepping.

Regan had already had two weeks “offline” preparing for his appearance at the royal commission, reading documents and familiarising himself with every detail of a disgrace that had occurred in the company’s financial planning arm, including shocking details catalogued in a dispatch that became infamously known as the “Clayton Utz report”.

It was a report on “fees for no service” and it had been commissioned by the AMP board to get to the bottom of the murk discovered in 2017 when AMP’s top lawyers discovered evidence that it had been no accident — as the company had claimed — that AMP billed countless customers for advice they never got. The digging that produced that evidence was in response to a years-long ASIC investigation.

AMP could have been in no doubt that the royal commission was chasing details on this dirty chapter at the company. Most of Regan’s witness statement, filed a week before his appearance, was devoted to explaining the fees-for-no-service scandal. This witness statement was AMP’s response to questions received from royal commission lawyers.

On the Thursday and Friday before his two-day appearance starting on Monday April 16, Regan had been extensively briefed by AMP’s external lawyers, led by barrister Philip Crutchfield QC, on how to handle his role as a witness.

Tuesday was Regan’s second day in the box. By the time one of the young lions assisting the commission, barrister Michael Hodge QC (tagged “Babyface” in the press for his youthful appearance), had finished with him, Regan agreed that AMP had misled ASIC at least 20 times.

Hodge, who struck a dogged and serious note — offset by a head of high hair and clever glasses — had dragged Regan skilfully into discussing the murk of AMP’s disgraceful history of charging customers for services they had never received and the repeated lies to ASIC about the practice.

Regan had been shown a string of emails between AMP general counsel Brian Salter and Nick Mavrakis, the external author of the Clayton Utz report, as well as some from Brenner. Many of these emails discussed changes and edits to the report. Hodge had focused on requests from Brenner to Mavrakis to be specific about his findings clearing chief executive Craig Meller of any knowledge of the fees for no service. Hodge had steadily narrowed his focus, tightened his line of questions.

By late on that Tuesday, and just minutes before the commission adjourned for the day at 4.23pm, Hodge drew Regan into a concession that would ring loud bells and frame newspaper headlines for days to come.

Asked by Hodge whether the Clayton Utz report was truly “‘independent”, given the commission had put up slide shows of emails showing Brenner and Salter seeking changes and clarifications to different drafts, Regan responded that it was not for him to determine its independence.

Hodge closed in without a glint of mercy: “And do you feel any discomfort at having met with ASIC and said to them, ‘This is an independent report’, in light of what you’ve seen now?”

Regan replied, in a dizzying moment, “There is a level of discomfort, yes.”

Brenner was in Tokyo, Craig Meller was in Sydney, AMP lawyers and barristers were in the courtroom, and other executives were at King & Wood Mallesons’ offices in Melbourne, glued to the live stream.

When Hayne closed proceedings for the day minutes later, the barristers and lawyers made their way swiftly to chambers and then to Mallesons. Brenner, still in Tokyo, phoned AMP executives watching Regan in the box from Mallesons.

Regan had been eviscerated. The two days of evidence took a high personal toll. He took leave from work soon after and has not yet returned.

Within 24 hours of Regan finishing up in the witness box, Brenner would be on the Wednesday night flight from Tokyo back to Sydney after an electrifying day of board meetings by phone.

Within three days, AMP chief executive Craig Meller would leave the company. Within 13 days, Brenner herself would be gone. General counsel Brian Salter would be thrown under a bus — a sacrifice that seemed designed to save others.

Within three weeks, three directors would have resigned, two of them the night before being voted out at the AGM.

It was a catastrophic upheaval, rivalled only by the rancour in 1999 and 2000 in which an AMP chairman and four directors quit the board soon after removing the chief executive. That bitter period, however, had not followed allegations of lying to ASIC and cheating customers on a grand scale. Rather, it had been along more traditional lines: a misconceived takeover, a rampaging CEO, and a board unable to contain rivalries and mistrust within.

Regan, the silver-haired head of advice, had been slaughtered on the stand; but worse, Brenner’s own emails had been read out asking for clarification of Meller’s role.

Late in proceedings, Regan had been asked by Hodge about a phone hook-up between AMP and Clayton Utz on September 21, 2017, that included Mavrakis from Clayton Utz and lawyer Larissa Baker Cook from AMP. Meller had also been on the call.

“He was on the call, yes,” Regan said.

“Do you recall a discussion during that telephone call about Mr Meller’s name appearing in the report?” Hodge had asked.

“Yes, I do …” Regan said. He said Meller made the point that he was one of the people interviewed about whom there were no findings made.

Regan did not say how it came about that Meller knew already there had been no findings made in relation to himself.

“Did he ask for his name to be removed from the report,” Hodge asked.

“No. No,” Regan said. “He asked the question as to whether or not it was necessary for all of those people — of which he was one — to be included in the report.”

AMP was now in crisis. The media would go berserk about whether the Clayton Utz report was independent. The board held a hook-up on Tuesday night, deciding that Meller, due to leave later this year in any case, should take accountability. They began a discussion about Mike Wilkins taking over as acting CEO. There was another hook-up on Wednesday, April 18. If Brenner had anticipated a few pleasant days in Japan, she had been wrong. By Wednesday night, she was on a plane back to Australia.

Fees for no service

On Thursday, April 19, the board resolved details of Meller’s departure: Wilkins was to stand in as CEO and the general counsel, Salter, was to stand aside.

Meller’s departure would be announced on Friday, April 20.

But it was soon obvious that investors were far from sated. The share price had plunged and the company appeared to have been caught in a massive scandal misleading the regulator. There was agitation from all corners for more changes, and foremost among this, a call for Brenner to resign. From the moment Meller, had gone it was clear Brenner would be next. AMP had already conceded significant ground but it was far from enough.

Some directors began to press for Brenner to resign. They included director Holly Kramer, as would be revealed in numerous media articles. It was all quiet discussions about the future of the company — stability and accountability, nothing so crude as saving the furniture (and the other directors). This, after all, was not politics.

Brenner also had her supporters. And she had time, not much, but a few days, to wait for the new report commissioned from the lawyers regarding the preparation of the Clayton Utz report. Above all, Brenner needed a finding that she had done nothing wrong.

The Clayton Utz report had been presented to the AMP board last year — on October 16 — then personally delivered the same day to ASIC by Brenner, Meller, Regan and Salter.

Media debate raged for weeks after Regan’s evidence about whether ASIC had been assured by the AMP top dogs that this report had been prepared independently of AMP and was fully at arm’s length.

Patently, on the evidence before the royal commission, there had been numerous drafts and numerous changes made, much of it instructed by Salter, some by Brenner.

What did not come out in the wash for some time was the covering letter from Brenner commissioning the report. It stated the report was to be “independent” and it also made clear that this meant independent of the advice business under investigation.

It was not, however, ordered to be independent of everyone at AMP. Brenner had expressly stipulated in her covering letter that Clayton Utz would liaise with Salter daily. If any issues relevant to her leadership team emerged during this process, Brenner wanted them brought directly to her.

Clayton Utz revealed a disgraceful culture where executives in the advice business flagrantly ignored legal warnings and rounded up clients into buckets with impossible names like “BOLR” and “ring-fencing”, where fees could be charged to unwitting clients receiving nothing in exchange.

ASIC itself was unlikely to be focusing on whether the Clayton Utz report was independent.

It was evidently a report commissioned by and for the company. It would hardly consider it wholly independent of AMP.

As a regulator, the only truly independent report would be ASIC’s own.

ASIC had busted the practice of fees for no service in 2015. But AMP’s advice division had obfuscated in repeated statements over the years to the regulator, claiming system errors and oversights which it said were fixed. None of which was true.

ASIC had sharply expanded the depth and width of its document demands on AMP in 2017 and 2018. The regulator was looking for something that AMP had not produced. ASIC seemed determined to find out what, if anything, Meller knew.

In a letter from ASIC to AMP dated March 18 this year, ASIC financial services enforcement head Tim Mullaly cast doubt on one aspect of the Clayton Utz investigation and complained about AMP compliance on several issues. This included: “AMP’s failure until very recently to produce the relevant material pertaining to the FOFA Practice Proposition Steering Committee. This material does not appear to have been considered by Clayton Utz in the Clayton Utz report, potentially raising questions concerning the comprehensive nature of their investigation and the accuracy of the conclusions reached.”

The Future of Financial Advice steering group was a committee overseen by Meller to handle the transition of fees and rules for financial advice under 2012 government reforms.

The new laws would ban conflicted remuneration and would force planners to act in the best interests of clients.

Mullaly’s letter continued: “AMP’s failure to produce to date, the relevant material pertaining to the FOFA … (of which Mr Meller is recorded as being the sponsor and business owner) … and which appears to have overseen the work of various FOFA project streams …”

ASIC, itching for documents, was diving deep into the murk. It gave the impression that ASIC had had some kind of tip-off and was determined to investigate.

AMP’s internal search had found no evidence that Meller was implicated; Clayton Utz also found no evidence. Meller had denied any knowledge and Brenner had requested that if Meller knew nothing, this should be clearly reflected in the Clayton Utz report.

This intervention by Brenner would become a critical link in the chain of information sensationalised after it was revealed in the royal commission for the first time.

Why was the chairwoman so interested in clearing Meller’s name? The answer may have been that as a lawyer, Brenner wanted all the Is dotted, that as chairwoman she did not want the CEO smeared if he was innocent. But the commission’s focus on it raised more questions than it answered.

AMP’s review into whether Brenner, Meller or Salter had inappropriately interfered with the Clayton Utz report would be carried out by the same external lawyers who had seen AMP through the royal commission, including Regan’s evidence: barristers Crutchfield and Tamieka Spencer Bruce, and Tim Bednall from Mallesons. Now they would investigate the preparation of the Clayton Utz report into fees for no service.

Anger and denial

On Friday, April 27, a new thunderclap echoed above AMP. Counsel assisting Rowena Orr told the commission that it was open to find AMP committed crimes by deliberately misleading ASIC.

It was the denouement. That night, a board hook-up again wrestled with the problem of Brenner’s future. Some said later that Brenner accepted that she would have to go, for the sake of accountability, and to sate the markets and investors, but that she was not ready to name the date. Others said she was prepared but waiting for Crutchfield’s report.

Blow by blow, details of the pressure on Brenner, and the role of AMP executives acting as go-betweens with the board, emerged in the press during that week. This newspaper reported online, late on Friday night, April 27, that Brenner would resign at a board meeting on Sunday, April 29, to be replaced by Wilkins. With this scale of boardroom leaks, it was clear AMP had gone from something approaching business-as-usual to Lord of the Flies.

The Crutchfield report was handed to the board over that weekend as Brenner prepared to exit. The report found that no one on the board — including Brenner and Meller — had acted inappropriately in preparing the Clayton Utz report.

Brenner resigned at the meeting and a press release was issued the following morning, Monday, April 30. Brenner was given a graceful exit. Salter was fired for following orders.

The board announced it had been unaware of the number of drafts made, nor the extent of Salter’s interaction with Clayton Utz. This was despite the board receiving at least two of these drafts, and receiving an explanation from Salter about the final draft that explained it had been revised again as the chairman wanted changes to state that Clayton Utz made no findings against Meller. The board said that it had simply received the Clayton Utz report. It had not been a matter for the board’s approval.

In the annals of accountability, it was a statement that seemed to be out on the edges of the mushroom field.

The April 30 board statement did not mention that after having “received” the Clayton Utz report last year but not giving it “approval”, the board had set up a committee in October 2017 to look into: handling staff named in the report; reviewing governance and culture; and dealing with ASIC. That committee had included Brenner, Meller and Wilkins. It had met roughly every few weeks.

Brenner said she was honoured to have been chairman and was deeply disappointed by the issues at hand. She made it clear she accepted that she was accountable for governance and had acted always in the best interests of the company. She had, she said, been in discussions with the board about the appropriate course of action, including her resignation as a step towards restoring confidence and trust in AMP.

Brenner had been on the board for eight years and the AMP chairmanship had brought her into the top ranks of corporate Australia.

No matter the spin and the talk of accountability, it was a devastating blow. She was leaving a boardroom that had been far from united since the royal commission.

On Friday May 4, five days after Brenner quit, the commission released a trove of AMP documents that included the full emails referred to during the grilling of Jack Regan. Here finally, was some of the commission’s source material. It included Brenner’s own emails to Salter and also to Clayton Utz partner Nick Mavrakis.

On the same day, AMP issued a riposte to the commission, defending Brenner and also the board. AMP reiterated the board had had no involvement in the Clayton Utz report aside from receiving it; it had been surprised it said, about Salter’s involvement. Moreover, it said Mavrakis had attended the board meeting when the report was delivered and he had raised no concerns about the accuracy of the report or its preparation.

AMP said there was no evidence that Salter had made any changes that Clayton Utz did not agree with. The evidence had shown, AMP said, that Clayton Utz had verified the accuracy of statements in the report.

Given the company had already fired Salter with no clarity around the reasons, this all seemed like gobbledygook. There appeared to be no claims of wrongdoing anywhere, or against anyone in AMP world.

But with the royal commission yet to make its findings, a slew of class actions bulking up, and ASIC still sharpening its spears, those bad days may lie ahead.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout