Regulation likely as buy now, pay later sector booms while consumer concerns mount

That will change in 2021. The sector’s canny ability to fly under the radar is being shot down by its own success. There are niggling questions around hidden harm to vulnerable customers.

And there is a specific threat to the business model of Australia’s largest BNPL, Afterpay, which itself could trigger a much harder look at the sector by ASIC.

Afterpay is now a giant, a top 20 listed company bigger than QBE, Suncorp and BoQ combined. No 2 player Zip is bigger than Ansell or Nine.

This week, a Macquarie research note warned: “We see increasing regulatory pressure as one of the pain points which need to be tackled before industry recovery longer term.”

In an early sign that these BNPLs see regulation as critical, both have poached senior executives from ASIC. In late 2019 Afterpay took Michael Saadat, ASIC’s executive director for financial services, who had led an ASIC inquiry into BNPL. And from about that time Matthew Abbott, a senior executive in ASIC corporate affairs, started working for Zip.

Two big reviews are under way, one into the payments system by the RBA and one into the entire regulatory architecture (who should regulate what) by the Treasury. The coming reckoning involves top cop ASIC, the RBA, the government and the Treasury.

This is why lobbying in Canberra, from the Treasurer down, has been in overdrive.

Until now, BNPL has been allowed to rise outside of the Credit Act, unlike banks which are required to do credit checks on customers — “quite a feat” as CBA chief Matt Comyn told the House economics committee on Thursday.

From the get-go, BNPL pitched itself as an exciting innovator and disrupter to big bank credit cards. Media reports continue to print that it only makes up 1 per cent of the payments system (a 2019 figure). Afterpay argues it is not part of the payments system at all, but more like an internet platform.

Some of this is just not going to wash. Afterpay now says BNPL is 2 per cent of the payments system but that some put that figure at 4 per cent. BNPL transactions run to $10bn. Afterpay alone has 3 million customers. The question for regulators is how much this payment method is harming vulnerable users. ASIC head of financial services and wealth management Joanna Bird says: “A consumer might have a number of BNPL loans, and then have to take out other loans just to make those BNPL repayments on time. And plenty do just that.

“Our most recent report found that one in five BNPL users said they had cut back on or went without essentials like food to make repayments on time, and one in six took out an additional loan to make their BNPL repayments on time.”

Afterpay CEO and co-founder Anthony Eisen says far from doing harm, the top BNPL has turned the traditional model of harmful credit on its head. He says the average credit debt among Afterpay’s more than 12 million customers is less than $200 compared to $3000 to $4000 of credit card debt in Australia. “You turn a model around from what is a customer revolving debt entrapment model to something which is low value, transaction by transaction basis, and has protections which no traditional credit card ever did: at the first point of a consumer missing a payment, they can’t use the service again. It is impossible to revolve in debt.”

Afterpay critics argue the real problem is hidden. Vulnerable borrowers who want to use Afterpay can pile up debts on other BNPLs and particularly on credit cards. No one has the full picture.

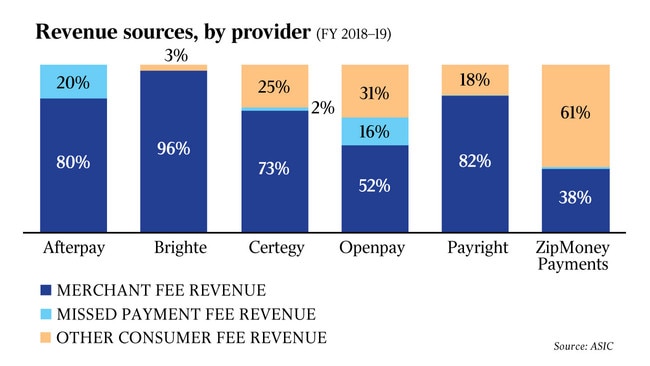

Confusing matters, there are many different business models of BNPL. According to ASIC’s November 2020 report, 60 per cent of Zip’s revenue in 2018-19 comes from other consumer fees.

Eighty per cent of Afterpay’s revenue comes not from the consumer at all, but from the merchants who typically pay a surcharge of about 4 per cent.

Eisen says at heart the Afterpay business is consumer-centric and was never a financial product.

“It’s a win-win for our customers because they don’t get charged for our service. The win-win for the merchant is that we direct more new customers and report customers to their businesses than they get from any other channel.”

The problem for Afterpay is that its business model is under attack.

At the moment, retailers are not allowed to pass the surcharge on to customers as they can do for credit cards. This allows Afterpay to call its service “free” for customers.

So far, Afterpay has convinced regulators that keeping the no-surcharge rule for customers encourages new players and more innovation in the payments space.

But what if the no-surcharge rule were lifted? Consider this scenario: merchants in sizeable numbers decide to pass on some or all of the surcharge to customers, and then consumers reduce their use of Afterpay, threatening 80 per cent of its revenue.

Asked if changing the no-surcharge rule could blow up Afterpay’s business model, Eisen says, “I don’t believe it does at all. If you wanted to break down our fee that we charged merchants, a very small component is in process-related costs which is where the regime has been traditionally focused. We are a better lead source than Instagram or Google or Facebook and we engender merchant customer relationships in a really data-driven and personalised way.”

Not all merchants agree that other services Afterpay boasts are worth it. Afterpay likes to compare its fees to internet platform marketing fees of 10-15 per cent.

How would Afterpay deal with a hit to its revenue model? Perhaps it would need higher late payment fees (in 2018-19 only 20 per cent of revenue) or financial servicing fees for the use of customer data. Any change like this raises the case for stronger regulation.

Joanna Bird says whether a surcharge passed on to customers becomes a “payment for service” or credit is a difficult question.

“If there is a cost for credit then it becomes more likely that the Credit Act will apply, but it is a very technical area. We would have to look closely at exactly what that charge was for. But exemptions to the Credit Act haven’t been fully tested in court yet, so we would probably need to obtain external advice.”

The hot decision over the no-surcharge rule falls to the Reserve Bank which is ruminating on BNPL. In December 2020, governor Philip Lowe, who chairs the bank’s payment system board, said the preliminary view was that “BNPL operators in Australia have not yet reached the point where it is clear that the costs arising from the no-surcharge rule outweigh the potential benefits in terms of innovation”.

But he also said that “over time a public policy case is likely to emerge for the removal of the no-surcharge rules in at least some BNPL arrangements”.

The governor said something else for careful listeners. The Treasury review of regulatory architecture is an opportunity for change.

It should come as no surprise that Afterpay wants to move decision-making from RBA to the Treasury. In its masterfully drafted 17-page submission to the Treasury’s BNPL review, Afterpay throws up a wall of arguments against regulation, including that it should not be considered part of the payment system.

Lobbying the government is far easier than the central bank or a regulator. As the Treasurer reminded everyone, “regulators must pursue their mandates in a manner that is consistent with the will of parliament. It is parliament who determines who and what should be regulated.”

Tougher rules for BNPL are being looked at overseas. In Britain, the Woolard Review recommends that BNPL should be regulated “as a matter of urgency”. It warned that for business models relying on merchant fees, like Afterpay’s, the system was set up to drive sales “without due consideration for the affordability of the commitment the consumer is taking on”.

Chris Woolard has been named as a possible contender to take over as chair of ASIC, along with acting chair Karen Chester, Joe Longo and John Lonsdale.

One sharp new regulation already baked in will hit Australian BNPLs in October. The regulator’s new design and distribution obligations, or DDOs, require BNPL providers to identify a target market and make sure that their products are fit for purpose for customers.

Last month ASIC acting chair Karen Chester flagged the regulator would be doing the rounds with company boards and managements to prepare them for DDOs. “This should reduce legacy trails of litigation, loss of shareholder value, and consumer harm. The first near-term cab off the rank will be buy now, pay later firms. We see the DDO as our regulatory lever to address the harms of BNPL in a precise and targeted way.”

Bird says ASIC will do risk-based surveillance on how industry has implemented DDO. “The BNPL industry will be one of our focuses early on in that surveillance phase. Depending on what we find, we will take appropriate enforcement action.

“We can only use the product intervention powers where a financial product has or is likely to result in a significant consumer detriment — it is a high very bar. However, the DDO requirements should be quite useful and we do expect to see some changes as BNPL providers bring their business practices into line.”

ASIC clearly believes it will move the dial on regulation. “The law makes it clear these are not set-and-forget steps,” warns Bird. “BNPL providers will have to monitor consumer outcomes and make changes if necessary to ensure that their products continue to meet the objectives, financial situation and needs of consumers.”

When asked about DDOs, Eisen says he is not averse to more scrutiny. “It gives the regulator dexterity to look at different models that are not all created equally. It’s very convenient for traditional credit providers to say ‘put everybody in the same bucket’ because it suits their business objective.”

Ultimately, ASIC may need to test the new obligations in court. One way or another, the future for BNPL is greater regulation. Not helping are the new guard of payment players like Beforepay allowing customers to access their wages before they land in their bank accounts. Regulators fear that without regulation, the harms will stay hidden.

How have they done it? In two short years buy now, pay later — where consumers can make payments in interest-free instalments — has become a market darling for its share performance and a government darling for its fintech innovation success. And all with the lightest touch of regulation imaginable.