PwC scandal: ATO tried to dob in Tax dodgers years ago

The ATO has revealed it attempted to dob in PwC over its tax conduct years before the recent referral to the AFP.

The Australian Taxation Office has revealed its frustration in dealing with PwC Australia the length of time it took to find the right authority to complain to after first uncovering the scandal in 2016.

PwC was referred by Treasury to the Australian Federal Police after it was found to have taken confidential information given to it by the government to help it develop international tax avoidance laws and then used that information to help global clients avoid tax.

“We are not afraid to take on the big end of town,” Commissioner of Taxation Chris Jordan told the senate estimates hearing.

“We have, and we will keep doing so. Our job is to protect the tax revenue that is due to the Commonwealth of Australia, revenue that we all depend on for vital services.”

PwC has been forced to stand down nine partners amid concerns over their links to the leaked confidential tax advice, with the chairs of two of PwC’s boards resigning and two other partners including the firm’s former chair also removed from the board.

Mr Jordan said in 2016 the ATO became aware of a “handful of multinationals suspiciously and quickly attempting to restructure their affairs upon the introduction of the Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (MAAL)”.

The ATO’s comments reveal tax authorities also put fellow firms KPMG, EY and Deloitte on notice over concerns PwC and its clients were seeking to circumvent new tax rules.

The ATO estimates almost $180m per year could have been lost from tax revenue due to the actions of multinationals using PwC’s advice.

It comes as Defence officials have revealed the department has 54 contracts with PwC, valued at more than $223m, including two signed this month after the scandal was revealed. The AFP, which is now investigating PwC, also has a current audit contract with PwC.

Defence chief financial officer Steve Groves has defended his department’s expenditure, saying the department was the government’s largest project delivery organisation.

“We are on a significant recapitalisation of the ADF and we use external labour as well as the significant APS and ADF workforce to deliver on those outcomes,” he said. In contrast, the ATO had significant delays getting the relevant information it needed from PwC – which it finally received in 2017 – as the firm attempted to claim legal privilege over tax affairs, which was subsequently denied.

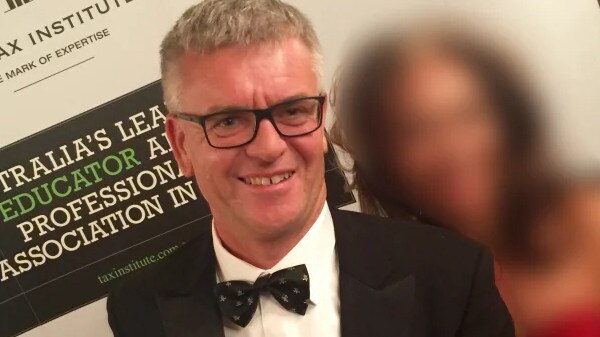

The former head of international tax at PwC, Peter Collins, has been referred to the Australian Federal Police over his role in leaking confidential tax briefings so the firm could construct schemes to allow clients to minimise tax.

Emails tabled in parliament by the Tax Practitioners Board revealed significant unauthorised disclosure of confidential Commonwealth information to 53 individuals within PwC by Mr Collins.

“The content received from late 2017 raised a range of significant concerns about artificial schemes being marketed by PwC,” Mr Jordan said. “A significant concern also uncovered was the Collins matter: a potential breach of confidentiality in a Treasury consultation process.” The tax commissioner also revealed the ATO attempted to get the AFP interested in investigating the leaks, with moves to refer the issue to the “correct authority” from 2018, when it shared information with Treasury and police.

Treasury deputy secretary for revenue Diane Brown revealed the ATO first sought information regarding a possible breach in February 2018.

But Ms Brown said Treasury was unable to ask for further information about the breach due to “secrecy provisions … They could not tell us.”

The irony that confidentiality provisions prevented the public from finding out about PwC breaching government confidentiality provisions was not lost on ALP senator Deborah O’Neill.

“Confidentiality became an impediment for advising Treasury that PwC was trying to rip off the Australian public?” Senator O’Neill asked Ms Brown.

“It does mean that it sometimes acts as a barrier,” said Ms Brown.

Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy said the department would “consider carefully” whether to use PwC for future contracts after confirming the embattled accountancy firm was its auditor in a $1m contract.

Greens Senator Nick McKim questioned how much confidence the public could have in PwC operating as the auditor with “unobstructed access to the Treasury”. PwC is also the auditor to a number of Australia’s biggest corporates, including Macquarie Bank and QBE. Just how long it will keep these key clients now that its misconduct has been referred to the Australian Federal Police remains to be seen.

“They clearly fail the pub test … it’s an absurd situation isn’t it?” said Senator McKim.

Mr Kennedy called out the “seriousness of their misconduct” but defended Treasury’s use of PwC for its internal auditing, saying it used different people to those involved in the scandal.

“Ongoing procurement is a matter we will consider carefully,” Dr Kennedy said.

PwC has attempted to argue it will “ring-fence” its Canberra business to protect $530m in Commonwealth contracts, but this was dismissed by Senators.

Greens senator Barbara Pocock said PwC’s behaviour was “aggressive harvesting” of information. PwC’s interim chief executive Kristin Stubbins issued a press release on Monday saying it had put nine partners on indefinite leave, but didn’t name them.

Pete Calleja, who headed up the firm’s financial advisory division, and Sean Gregory, PwC’s chief strategy, risk, and reputation officer, were among those placed on leave.

Governance board chair Tracey Kennair and risk committee head Paddy Carney have resigned from their roles.

The company has appointed Justin Carroll as chairman of the governance board.

Former PwC chair Peter van Dongen as well as corporate and global tax partner Paul Abbey both appear to have been removed from the firm’s board.

But PwC refused to confirm whether the two men were among the nine stood down, with spokesman Patrick Lane telling this publication “we have no such confirmation for you”.

Despite calls by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in parliament, Ms Stubbins has continued to keep the names of the rest of the 53 staff implicated a secret.

“There has been an assumption by some that all those whose names have been redacted must necessarily be involved in wrongdoing,” Ms Stubbins said.

In an open letter, Ms Stubbins said PwC had “a culture of aggressive marketing in our tax business” during the period the firm breached Commonwealth confidentiality agreements.

“Over a period, this aggressive behaviour and drive for growth permeated certain parts of our leadership and allowed for profit to be placed over purpose,” she said.

The Australian has already named two of the people, being PwC managing partner for People Helen Fazzino, and the new PwC head of tax Chris Morris, who was promoted as a result of the scandal after his predecessor was forced to step down. These were two of the 36 named on a list circulating within PwC – a list that involves the firm’s key tax team.

It is not suggested any of those copied into the emails had knowledge of, or were involved in, the tax scandal.

Additional reporting: Ben Packham