Morgan Stanley’s James Gorman offers first-hand lessons in beating the virus

After catching coronavirus, Wall Street’s most admired banker has a warning for Australia.

In March, James Gorman caught the virus. By mid-April he had kicked it. Few would understand the crisis better than the New York-based chairman and CEO of Morgan Stanley. One of 10 children, Gorman grew up in Melbourne, rising to become Wall Street’s most admired banker and this year was awarded the Order of Australia for his work.

“I’ve got an apartment there that I lived and worked at for about 80 days straight, and that was pretty isolating,” Gorman describes living in downtown Manhattan through the grim peak of COVID-19, when New York had 10,000 new cases a day.

“I’d go for a little walk around the streets around 10 o’clock at night. There was nobody on the streets, so that was eerie, that was back to New York in the 80s. Then I got sick and was stuck in the apartment again, having to feed myself and get through that on my own which was a challenge at the time.

“New York is incredibly resilient, but this has hurt.

“We had all the protests from the racial unrest, so there’s been a whole series of things that have gone on, economic, socially, and health wise that have made the city tough to live in. I’ve watched what Australia’s going through with COVID and I’ve a little bit of envy. I know it’s been tough down there, but we were having 700 people dying a day in New York for weeks on end, it was pretty extraordinary.”

In a rare interview for the Sky News series The Alliance, Gorman warns Australia not to mess with its AAA credit rating and says the country should use the $2.7 trillion superannuation savings to drive business growth.

He also talks frankly about how he and the board managed the risk of an internal crisis on learning that he had been struck with COVID-19, just as it took hold on New York.

“I told the board, I told our regulators and just told a couple of executives, but I didn’t want the attention to be about me,” he says. “It had to be about everybody else and the company and our clients and I just felt like we needed to weather that storm.

“I described it to the board as I’m sick but I’m not ill. I was not hospitalised. There’s a big difference and fortunately I’ve remained pretty fit for the last decade,” Gorman adds. “I do a lot of rowing on the machine and maybe that helped my lungs.”

The board supported Gorman’s actions. “I said to them if it gets really serious, then obviously we make it public, but until that point we just manage internally and I was fortunate I got through this. A lot of others have not been fortunate, it’s been tragic.”

Results

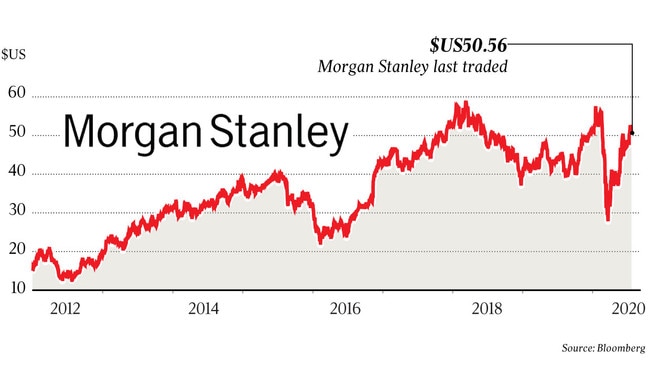

We speak on results day for Morgan Stanley’s second-quarter earnings, in what has been a rollercoaster six months for Gorman. Incredibly, it is the best result in 85 years. The bank, which has a market value of $US80bn ($112bn), continues to pay dividends and, what is more, despite soaring US unemployment, it has not lost one job to COVID-19.

“It’s been a 10-year journey,” he says. “We came out of the last financial crisis very damaged and we took a lot of illiquid risk positions which hurt our company. We vowed we’d never be in that position again, so we took what was great about Morgan Stanley in the last 85 years and we augmented it with a lot of stability.”

Gorman decided to shift the business away from the more risky parts of trading. Today, the bank is the world’s third-biggest wealth manager.

“We were ready for prime time when this came along,” he says. “This was exactly what we had been effectively training for, what we had told our board we needed to be prepared for. We didn’t know the exact shape of the crisis and obviously the healthcare aspect of this and everything else makes it truly unique, but we did know we would face these kinds of markets again.”

In what he calls a conscious decision by himself and the board in February, Gorman’s commitment on jobs was one recent example of how he has brought a different culture to Wall Street.

“In fact I asked the operating committee to vote on it and it was unanimous, that we would not lay off anybody in this company this year whatever happened with the crisis. And somebody said, ‘Well, what about shareholders?’ and I said, ‘Well, sometimes shareholders have to stand behind the employees.’ A number of other companies followed us.

“Now it turned out we’ve actually had a record-breaking quarter so it feels now like it was sort of an unnecessary gesture, if you will. But at the time it was very heartfelt and I felt we needed to take the anxiety of our job security off people’s shoulders. They had enough to worry about with the health crisis and what was going on with their families and they didn’t need to worry about their job at Morgan Stanley.”

National crisis

We move on to the national crisis — managing the spread of the virus and the capacity of the health system balanced against jobs and livelihoods. Here, Gorman is urgent, almost angry, at the lack of progress.

“We’ve got to nip this second wave in the bud: Texas, California and Florida each exhibiting 10,000 cases a day. This is insane. It’s not like this is new. We have been living with this since first China then Iraq then Italy — this has been several months of learning. Across all of Europe now it’s basically being controlled.

“People need to get with the program, it’s pretty straightforward: social distancing, wear a mask, respect the health of others, isolate if you feel unhealthy or if you need quarantining and then your economy and the country can keep moving. They’re not doing that in certain states and until they do that you won’t see the reversal that we’ve seen in the northeast of the US.”

Lessons for Australia

On the economy, there are lessons for Australia. Gorman acknowledges the difficulty of authorities making judgments in times of crisis, but he bemoans the true cost of a full shuttering, as Americans describe it.

“We have seen enormous damage from completely shutting businesses and I do think we could have kept businesses open with appropriate social distancing and protocols about cleanliness and mask wearing and so on without completely destroying businesses.

“We have made the recovery much deeper here, the problem much deeper, and if I ran Australia I would be careful not to overreact — I mean the long-term social, mental health costs of putting so many people out of work to protect perfection is a trade-off I would be very careful about making. What we are experiencing in New York now is that we can still have 700 cases a day with no acceleration, yet the city is opening up.”

As America heads into the election, the nightmare for the next president remains inequality. “The working class have essentially not seen any real wage increase for 30 years, I mean it’s shocking,” says Gorman. “The minimum wage in some states at $7 an hour is just ludicrous. The second inequality is obviously racial inequality. I’m hopeful that the recent protests have created an inflection point for the racial discussion where everybody sees it as part of their mission to be part of the solution.”

In more normal times, Gorman would visit Australia every year and clearly cares deeply about the country. He led Wall Street’s response to the bushfires that brought so much misery ahead of the pandemic, personally donating $1m to the cause.

Economic security

“Like all Australians, whether at home or abroad, my heart goes out for those affected by the fires,” he posted at the time. “The loss of life, property, livestock, wildlife and beautiful countryside is deeply upsetting.”

Every day, Wall Street helps fund Australia’s big four banks, which in turn are now underwriting the transition to recovery. Unsurprisingly, Australia’s economic security is of great interest to the Morgan Stanley chief. After last week’s economic statement, Australia’s AAA rating was confirmed by credit agencies, but the October budget will almost certainly see an increase in the $184bn budget deficit for next year.

Gorman, who sits on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York board, has some advice for the Australian government.

“The AAA rating is not something to be messed around with,” he says. “That’s a massive sovereign risk advantage for Australia. It clearly helps the ratings of the banks that are operating in the country, they’re all AA-rated banks I think. It is very important. I would not give that up.

“Australia is a very prosperous country but it is a relatively small country with a small population. It is dependent upon foreign institutions and foreigners buying a lot of what Australia makes and produces. Having a very stable sovereign risk and stable banking system is essential to the economic balance in the country.”

Gorman also sees opportunity for Australia to unlock its own financial base to drive growth where it has a natural advantage, especially in newer technologies.

“I would use the asset pile that Australia has developed over 30 or 40 years. It’s a stroke of genius, the super funds. It has set Australia up with a level of stability which is the envy of most of the world. These are the times when you take advantage of that. I would encourage the super funds to diversify and invest directly in the country and some of the infrastructure of the country, the businesses of the country that need support coming out of this crisis.”

Whether Gorman ever returns to live in Australia is too early to tell. But he reaffirmed his desire to contribute more directly. “I’ve a lot of years left to go hopefully to contribute and I’ve done a lot of things here with Federal Reserve boards and other things, so I would love to do something to help Australia.”

The Alliance partners will need to tread different paths back to full health, as the pandemic runs its course. Gorman calls it “somewhere between a U recovery and slightly longer than that” recovery.

“People are thinking that because we are returning to our offices that the economy is recovered, that isn’t so. This is not going to be a rapid turnaround, this is going to take a couple of years.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout