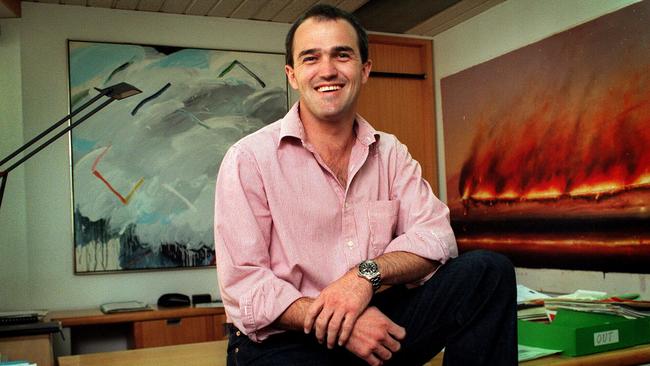

Johnny Kahlbetzer talks up his new Twynam Earth Fund

Straight-talking scion Johnny Kahlbetzer pulls no punches that his new $50m Twynam Earth Fund is only for those ‘crazy, smart and gutsy’ enough.

Johnny Kahlbetzer has always been known as a straight-talker in business since the day he joined his famous father’s Twynam Agricultural Group, once one of the nation’s biggest rural landholders, in 1991.

So unsurprisingly the 56-year-old doesn’t mince words when speaking about the proliferation of environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment funds that have emerged across the world in recent years.

“This whole space is getting hotter and hotter. We believe that there are very few funds that actually focus on serious decarbonisation. My view is the majority of funds are fluffy ESG funds, even if they say they are decarbonisation focused,” he says.

“They are not chasing technologies that can really make a change. That has been a core focus of ours. I can put my hand up and say we are one of the few in the world really laser-focused on trying to find those companies that can make a difference.”

Attending the COP4 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Buenos Aires in 1998 solidified and strengthened the Kahlbetzer family’s resolve and commitment to decarbonisation after Johnny’s father John, a German immigrant, had first come to Australia in 1954 and amassed a rural empire.

For over 25 years Twynam has deployed significant capital into decarbonisation and is now backing a range of businesses involved in green technologies, sustainable farming and renewables.

Those investments spawned the start of serious work last September on Twynam’s first public investment fund, which is now being pitched to investors as The Twynam Earth Fund.

As Kahlbetzer puts it, the new fund will “invest in and grow businesses with teams that are crazy enough to think that they can change the world, smart enough to work out how and gutsy enough to do it, while striving to generate leading returns”.

The fund will cornerstone early-stage equity investments into decarbonisation and environmental technologies.

He will be the fund’s inaugural chairman and Twynam Investments and the Kahlbetzer family will be seeding the fund with $US5m as it builds to an initial raising of $US50m.

“Ideally this will be a start of something,” he says.

“We need to see how the market is. It would be great if we could get to $US200m over a period of time but there is no firm fund raising target and we are just focused on the $US50m to start. We do have some early interest from families . One is a well-known US family, then there is a Singaporean group and an Australian family.”

Over the last five years the Twynam Funds Management team has managed an in-house portfolio of 15 early-stage decarbonisation and environmental technology investments worth over $US20m.

These include firms converting waste cotton fabrics into new fibres for clothes, recycling organic waste through insects, recycling CO2 into chemicals and fuels, and supporting the production of alternative protein sources.

Separately, Twynam also funds the World Wildlife Foundation’s program to eliminate plastic in Australia and is working on ocean clean-ups across the globe.

“There are certain areas we really need to find solutions to. How we are dealing with waste is highly critical, a problem on which government and society need to have a change of view.

“Putting everything into landfill isn’t sustainable and recycling has its issues. I believe we should recycle the easy stuff and the rest should be used to fuel waste to energy projects,” Kahlbetzer says.

Twynam has a stake in Australian waste-to-energy business Sierra Energy.

“The Environmental Protection Authorities of each state need to have dramatic changes of thought on this technology. Governments need to lead it, to look at what we are doing with our waste. There is waste to energy technology out there in the world, but generally you just can’t get it in Australia.”

All that gas

The rural-turned-tech scion has strong views on the Australian energy transition, especially the need for gas to play a central role in the shift to renewables.

“We should have had a domestic gas reservation system from day one. But politically they decided not to. Now we are having to backtrack,” he says.

“Gas is 100 per cent required for a successful transition to renewables. The Greens and other environmentalists who say we have to stop production and the exploration for and development of gas wells don’t understand how the transition works. Coal for domestic consumption can certainty be transitioned out of more quickly, but that is a different question.”

Kahlbetzer’s long-held belief that batteries will remain very expensive for long duration energy storage has underpinned since 2009 Twynam’s investment in a private Sydney-based firm known as Vast Solar, which has been developing proprietary technology in concentrated solar power (CSP). Unliked most photovoltaic (PV) solar panels which convert light into electricity, CSP uses mirrors to focus sunlight onto a receiver which then gathers the sun’s energy as heat in sodium. This allows it to be stored more effectively and provides power after dark.

This week Vast Solar agreed to combine with Nabors Energy, a global provider of advanced technology for the energy industry and an affiliate of the US-listed oil and gas drilling fleet owner Nabors Industries,

The deal will take the Australian company public in New York on the Nasdaq at a valuation of up to $US586m, but it will remain headquartered in Australia.

It offers Vast the opportunity to leverage Nabors’ global supply chain and operational footprint, advanced engineering and manufacturing capabilities, as well as its significant expertise in robotics and automation.

Earlier this week Vast also secured a $65m grant from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency to support the construction of a 30 megawatt concentrated solar plant with 12 hours of storage at full power at Port Augusta in South Australia.

Vast is also working with the state and federal governments to identify the site of its first full-scale manufacturing facility, which will produce Vast Australian designed and made CSP technology.

For Australia, Kahlbetzer believes the Nabors deal has potential to bring inward investment in the sector, create jobs, and reduce emissions.

He also claims it could be a catalyst for building a world-leading CSP industry in Australia and helping it become a clean energy export superpower.

But he is also relieved Twynam’s punt on a new form of solar power more than a decade ago has so far paid off. The Kahlbetzer family will take no money off the table through the NASDAQ listing and will roll all its shares in Vast into the new vehicle.

It will also put an additional $US15m of new equity into the combined entity – a so-called listed Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) – as will Nabors.

“It is justification for spending 13 long, arduous and at times very stressful years. But this announcement is just the first step, the next three months are still crucial,” Kahlbetzer says.

“It is just great to be part of what was once an idea and have it taken through the development stage. I have learned plenty and if we did it again, I would certainly go about it in different ways. This is also why our Earth Fund makes sense. With Vast, we have shown we can be involved in a company from the idea stage all the way through to a public listing.”

He says Twynam considered raising more money in the private markets for Vast before settling on it going public.

“This deal, given the knowledge and skills base of Nabors, was better. Going public you have a lot more compliance issues we have to be aware of and yes you are answerable to a lot more people. But given the scale this will grow to, we will need a lot of external capital,” he says.

Global retreat

At its peak as a landowner fifteen years ago, Twynam boasted 22 broadacre cropping, livestock and citrus holdings across Australia and owned the Colly Farms cotton business, making it one of the nation’s largest agricultural producers.

A quarter of a century earlier Johnny’s father John had also created a vast Argentine agricultural operation known as LIAG, which owned 80,000 hectares of cropping and livestock country in the South American nation.

But after the global financial crisis, the Australian land portfolio was progressively sold down, aided by the Rudd government’s $3.1bn water buyback program, which in 2009 saw the controversial purchase of 240 million litres of water from Twynam for a record $300m.

The same year John Kahlbetzer supported the creation of BridgeLane Capital, a venture capital firm run by his younger son Markus, which was seeded with cash and ownership of the Argentinian rural assets.

Johnny, 16 years his brother’s senior, was handed responsibility for Twynam.

Since then BridgeLane has invested in the online/mobile technology, sustainable food and agricultural robotics sectors.

Last year, spearheaded by Markus, the family decided to offload the LIAG assets in Argentina to the family of Gerardo Bartolome, the founder of global soybean powerhouse GDM Seeds.

The $US201m sale was the largest agricultural transaction in Argentina’s history and reflected the Kahlbetzer’s ongoing concerns about the country’s prolonged economic crisis.

“It was Markus’s decision but we discussed it as a family. We were all somewhat sad about it but the reality is Argentina is hard work. It has been hard work for a long time. I managed that business for many years so saw it first hand,” Johnny says.

“We are seeing this debate currently in Australia and America about Central Banker’s efforts to control inflation but in Argentina, we have seen the price of letting inflation run. Once the genie is out, you can’t put it back in the bottle.”

Now all that is left of the family’s rural empire in Australia is two small farms – named Wingello Park and Johnniefelds, together spread across 1400ha near Marulan, south of Sydney.

There Johnny has a family “weekender” and oversees breeding Angus cattle and polo ponies in a regenerative manner, preserving traditions that have been part of Kahlbetzer family history.

Late last year his deeply private father, who just turned 92, returned to the country where he made his fame and fortune to spend the final years of his life in Sydney.

It was almost two years since he ceded all his economic interests in the family empire to his two sons under a textbook succession plan.

“Markus and I now see him more regularly, especially with the grandkids,” Johnny says.

“After spending so long abroad, he is certainly happy to be home and with his family.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout