‘Conflicted’: warning on big four auditors

The major accounting firms are ‘inherently conflicted’ by earning consultancy fees from the same top 20 companies they are hired to audit.

The major accounting firms are “inherently conflicted” by earning hundreds of millions of dollars in consultancy fees from the same top 20 Australian companies they are hired to audit.

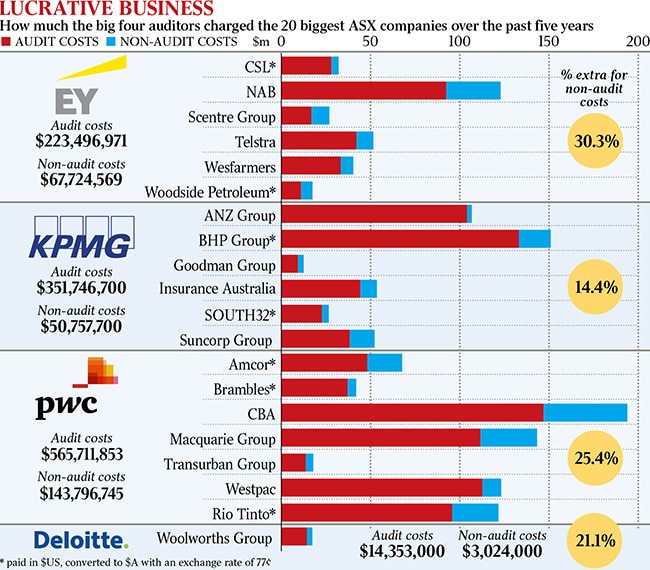

PwC, KPMG, Ernst & Young and Deloitte have pocketed more than $250 million over five years for providing additional services to their largest audit clients.

Former competition regulators Allan Fels and Graeme Samuel are calling for the big four accounting firms to be banned from providing consulting and tax advice services to companies they are auditing. Such a move would cost them hundreds of millions of dollars.

Analysis by The Australian shows that contracting fees — worth a total of $265m — amount to one-fifth of the fees the big four accounting firms are charging the 20 biggest Australian companies.

Mr Samuel, a former Australian Competition & Consumer Commission chairman, criticised the practice as “inherently conflicted” and suggested Australia follow the lead of Britain’s Competition and Markets Authority, which last year proposed legally preventing the provision of both audit and non-audit services to clients. The big four accounting firms have since voluntarily agreed to forgo consulting work for audit clients in Britain, but there has been no move to adopt the policy elsewhere.

“This is the one area where there is a problem, because there is an inherent conflict of interest when you’ve got very large consulting work being done by the same firm doing the audit work,” Mr Samuel said.

“What we’re seeking from auditors is independence: the capability to make a judgment that is based on an independent view rather than one that is compromised.

“We want the quality of the reports to be impeccable. I want to see the intellectual integrity of the audit is assured.”

Auditing firms are legally required to provide assurance that corporate financial statements give an accurate and fair view of a company’s financial position, liabilities, profits and losses. However, the quality of audit work has been criticised by global regulators, amid concerns about conflicts of interest at the big four accountancies as they focus more on consulting work.

Professor Fels, the inaugural chairman of the ACCC, said the government should consider breaking up the major accounting firms to ensure their auditing businesses remained independent.

“The Hayne royal commission showed big businesses don’t handle conflicts that are built into their operating structures well, and I fear that this is happening with auditing,” he said.

“We do need to consider whether there should be structural separation of auditing and non-auditing work. Structural change must be on the agenda.

“Australian audit firms have been a bit slow off the mark in making internal changes that would deal with these concerns. They may find they’ve arrived too late, having done too little.”

There is no standard way of reporting non-audit work across the ASX20 group, which means some company financial accounts combine audit-related fees such as assurance or regulatory work into audit figures. Other companies provide a more thorough breakdown of other fees paid to auditors.

Deloitte, PwC and KPMG declined to respond to requests for comment.

EY Oceania chief executive Tony Johnson said the top goal of auditors was audit quality. He said non-audit work was decreasing as a share of revenue as both auditors and clients tightened their policies and processes.

However, Mr Johnson said that when auditors were engaged it was because “companies believe the auditor is best-equipped to perform that work because of their skills, knowledge, objectivity and independence”.

“Audit partners are not allowed to be, and are not, incentivised, measured or rewarded on winning non-audit work at audit clients,” he said.

A parliamentary inquiry will this month hold a series of public hearings into the accounting firms over conflicts of interest, poor audit quality — which can help trigger corporate collapses — and the tight-knit relationship between government and the big four accounting giants.

Labor senator Deborah O’Neill, who established the parliamentary inquiry, said audit work risked becoming the “poor cousin” of more lucrative services.

The share of revenue at the big four firms from audits of financial statements has shrunk from an average 24 per cent to 18 per cent over the past five years.

“When ASIC has been reciting that there’s a problem here since 2012, it needs to be given the light of day,” Senator O’Neill said.

“We need to see if there’s a fire underneath this, given the change to those businesses.”

In its most recent transparency report, Deloitte said it had earned $278m for auditing financial accounts in 2017-18, while picking up $117m from those same companies for non-audit services.

KPMG said 20 per cent of its $1.64bn revenue in 2017-18 came from auditing, while 8 per cent was earned from non-audit work for its audit clients. PwC earned $409m for auditing, against $218m for other services provided to audit clients. EY earned $365m in audits and related services for its audit partners, but did not provide a breakdown of the fees.

The Australian revealed on Tuesday that some of Australia’s biggest companies had failed to change auditors for decades — in one case for 65 years — and the average tenure of auditing firms employed across the ASX20 group had risen to 22.4 years, which was longer than the maximum 20 years allowed under European laws.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout