Climate change to transform banking, S&P warns

Banks must do more to protect their operations in the face of climate change, according to a report by Standard & Poor’s.

Climate change could radically transform the way banks operate and have a greater influence on their creditworthiness as some lenders will be better prepared than others, according to a report by Standard & Poor’s.

S&P cited studies showing the value of global financial assets could fall and losses could increase “exponentially” in line with an expected increase in temperatures between 2015 and 2100.

“Understanding the main climate change risks for the banking industry is of paramount importance for banks to minimise the future climate-related costs and the impact on their creditworthiness,” the report said.

There has been no cohesive global effort to address the issues for banks and not all banks were moving at the same speed to incorporate key climate change risks, establish priorities or implement best practice.

Appropriate benchmarks to monitor risks were still unclear.

This was despite direct and indirect effects on businesses from an accelerated rise in global temperatures and more frequent extreme weather events, and the likelihood of direct human consequences such as migration and water scarcity.

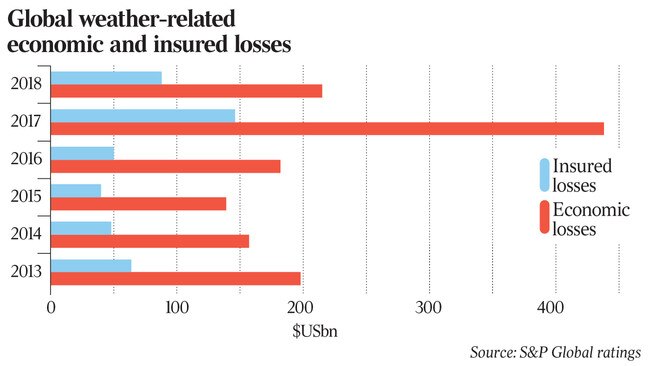

S&P cited data from the Network for Greening the Financial System, which showed the number of extreme weather events had more than trebled since 1980.

Also, in the past eight years, worldwide economic costs from natural disasters had exceeded the 30-year average of $149 billion a year. With non-life insurance coverage representing less than 10 per cent of GDP, even in developed countries, the proportion of uninsured losses from such events fell directly on households and balance sheets.

“This could lead to a significant increase in credit risk for banks stemming from decreased debt-repayment capacity, impaired collateral values and higher leading costs,” S&P said.

“Severe weather events could also stunt economic growth, hamper employment and weaken national infrastructure.

“As a result, they may restrict governments’ budgetary flexibility and increase their contingent liabilities, weighing on their creditworthiness.

“In turn, higher sovereign risk could erode the value of government securities in banks’ investment portfolios.”

On transition risks, S&P said there had been little progress in awareness of climate change risk or the opportunities associated with moving towards an economy with low carbon emissions.

This represented the biggest challenge for bank risk management frameworks, with the volatility of asset revaluations dependent on how quickly economies achieved the goal of keeping annual global temperature increases to less than 2C.

Companies that took a long time to adjust to the low-carbon transition could experience a decline in creditworthiness, weakening the asset quality of banks lending to them or investing in their debt instruments.

S&P said transition risk was particularly relevant for institutions with large exposures to carbon-intensive industries such as automotive, oil, gas, energy and coal. While S&P considers climate change risk and the potential for disruption to banking systems in its creditworthiness assessments, the agency said it was difficult to quantify some of the risks and opportunities.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout