Big four banks in great interest rate cuts rip-off

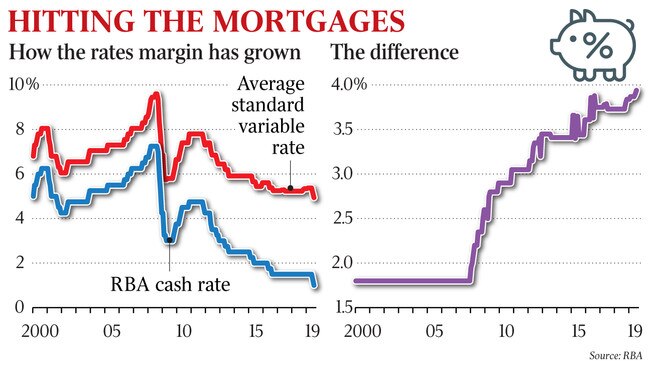

Mortgage interest rates are nearly 4 percentage points higher than the Reserve Bank’s cash rate than 2008.

The major banks have been squeezing households by withholding the equivalent of eight separate rate cuts since the global financial crisis, leaving average mortgage interest rates nearly four percentage points higher than the Reserve Bank’s cash rate.

Back-to-back cuts in the cash rate to a record low of 1 per cent have pushed the difference between the RBA’s cash rate and the standard variable mortgage interest rate to a 25-year high of 3.94 percentage points.

The major banks said it was becoming more difficult to move in line with the RBA given the current regulatory environment, capital requirements and funding costs.

Between 1997 and 2007, the average standard variable rate moved in lock-step with the cash rate, maintaining a 1.8-percentage-point gap. Since then, the gap has crept up steadily as banks have either failed to pass on official rate cuts in full or increased their mortgage rates by more than official increases.

“It’s a giant tax on households,” said a bank analyst who declined to be named.

A home owner with a $500,000 loan with one of the big four banks is paying between $10,550 and $10,800 more a year in interest than they would if banks had kept rates in line with the RBA cash rate. On a $1 million loan, the extra interest would be up to $21,600 a year.

In its assessment of competition in the financial system last August, before the RBA cut the official rate last month and this month, the Productivity Commission identified the trend.

“Despite the cash rate’s remaining at record low levels and the decline in the cost of wholesale funds, (banks) have widened the spread between the cash rate and their housing lending rates,” the commission found.

“This enabled them to maintain relatively stable profit margins, even when changes to prudential regulation increased their costs and eroded return on equity.”

A Westpac spokesman said the cash rate was “a small component” of the funding costs of mortgages and funding costs had “significantly increased compared to pre-crisis levels”.

“In addition, to ensure that we have stable funding, there has been increased competition in attracting and retaining deposits,” he said.

The spokesman cited higher term deposit interest rates relative to the 90-day bank bill swap rate — a key measure of bank-funding costs.

An ANZ spokesman said: “Deposits fund a significant amount of our home lending, and as interest rates move lower, it is more difficult to adjust deposit prices in line with changes in the official cash rate.”

Major banks’ net interest margin, the gap between average lending and borrowing rates, has fallen from about 1.8 per cent in 2008 to about 1.6 per cent.

The Productivity Commission said the Australian Prudential and Regulatory Authority’s view that “competitive pressures” could prevent lenders from passing on increased costs had “not eventuated”.

“The bulk of these costs have been passed on to new and existing borrowers, resulting in a widening of the spread between the cash rate and interest rates charged,” the commission said.

A Commonwealth Bank spokesperson said the Reserve Bank’s official cash rate was one of many factors considered.

“When pricing our home loans, we consider a range of factors including the current monetary policy settings, our regulatory commitments, capital requirements, community expectations, and the current funding environment,” she said.

While the Reserve Bank lowered the cash rate by 50 basis points at its past two meetings, the Commonwealth Bank and NAB reduced their standard variable mortgage rates by 0.44 percentage points, ANZ dropped its rate by 0.43 percentage points and Westpac held back the most, lowering its rate by 0.4 percentage points.

The cash rate was “an important determinant of banks’ funding cost … [because it] acts as an anchor for the broader interest rate structure of the domestic financial system”, Reserve Bank economists concluded in their March Bulletin.

Analysts said the reduction in the number of competitors since the 2008 financial crisis and the decline of the securitisation market, which helped smaller lenders compete with the majors, had increased the big four banks’ market power.

In its mortgage pricing inquiry released last year the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission found it wasn’t in the major banks’ interest to compete over lending rates because they could more easily make extra revenue from lifting them rather than trying to win new customers.

“The accommodative and synchronised approach to pricing we have previously observed among the big four banks … was not unexpected and is enabled by the oligopoly market structure,” the ACCC said.

The big four banks held around 80 per cent of the $1.7 trillion of outstanding mortgages in May, of which $560bn were for investment properties.

The additional 2.14 percentage point spread between the cash rate and the standard variable rate since January 2008 equates to a cumulative $2.1 trillion in extra interest for the big four banks alone. according to an analysis by The Australian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout