Banks turn off the loan tap for investors

The big four banks all but turned off the tap on writing investor loans in the year ended November 30.

The big four banks all but turned off the tap on writing investor loans in the year to November 30, exercising more caution in riskier parts of the $1.7 trillion mortgage market.

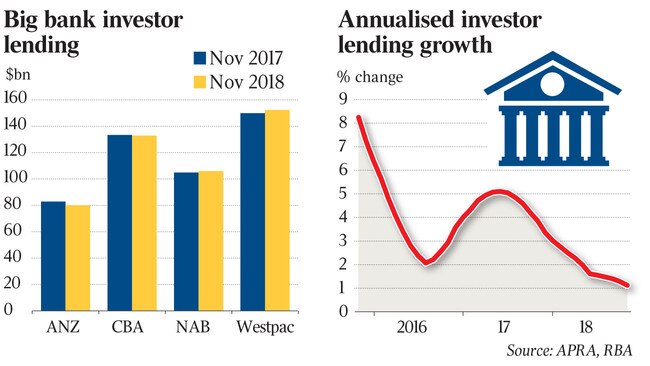

The latest Australian Prudential Regulation Authority banking statistics, released yesterday, showed negligible growth across the major banks’ investor loan portfolios as at November 30. The combined investor loan books of the big four amounted to $471.4 billion, compared to $471.1bn in the same month in 2017.

The APRA statistics showed the Commonwealth Bank’s investor loan book contracted to $132.8bn in November, from $133.3bn a year earlier, while ANZ saw a sharper reduction from $82.9bn to $80.2bn.

Westpac’s investor loan book edged up to $152.3bn as at November 30, from $149.9bn a year earlier, while National Australia Bank saw its portfolio rise to $106.1bn, from $104.9bn.

However, the flatlining among major banks masks early signs that at least two of them are beginning to use challenger brands to cut rates and dip back into the investor mortgage market.

Analysis for The Australian by comparison site Finder shows that in the past two months Commonwealth Bank has reduced the rate on at least one investor loan product at subsidiary Bankwest, while Westpac has cut a raft of investor interest rates across its St George, Bank of Melbourne and BankSA loans.

Westpac led in the market share stakes for household investment loans in November, accounting for about 27.3 per cent, followed by CBA at 23.8 per cent, NAB on almost 19.1 per cent and ANZ at about 14.5 per cent, APRA’s data showed. In the same month in 2017, CBA had the largest share.

Several of the major banks argue the sharp pullback in investor loans is reflective of demand coming off the boil, but obviously wider interest rate differentials also work as a deterrent. The Reserve Bank on Monday released numbers showing growth in lending to property investors tumbled to the slowest rate since it began collecting the data in 1990.

Credit extended to property investors rose 1.1 per cent in the year ended November 30, while lending to owner-occupiers increased 6.8 per cent.

“It’s just a matter of time before they (the big banks) start to accelerate their lending, and I’m not convinced the demand is not there,” said Hasan Tevfik, a strategist at independent research house MST.

“Balance sheets are fine — they have protected their margins — but the growth is just not there.”

Mr Tevfik said the RBA and Council of Financial Regulators had made it clear the lending pullback in some parts of the market had gone too far, particularly amid tentative signs of an improvement in household debt-to-income ratios. But the failing health of the housing market remains a key focus for borrowers as prices in many parts of Australia remain under pressure.

National dwelling values dropped 4.8 per cent in 2018, reflecting the weakest housing market since 2008, new analysis by CoreLogic showed yesterday. Sydney prices fell 8.9 per cent over 2018, while Melbourne was down 7 per cent.

Other cities saw smaller declines, with Perth values dropping 4.7 per cent and Darwin down 1.5 per cent.

The outliers were Hobart and Canberra where values increased 8.7 per cent and 3.3 per cent, respectively.

Regulators have tried to manage the slowdown in housing credit.

This includes APRA’s decision to scrap lending limits on interest-only loans from January 1, which followed the axing its 10 per cent speed limit on bank lending to property investors in April 2018.

But some analysts are not convinced the measures will work as banks navigate the Hayne royal commission and look to adhere strictly to their responsible lending obligations.

Morgan Stanley analyst Richard Wiles has said he doesn’t expect the lifting of restrictions by APRA to drive a rebound in the major banks’ housing loan growth.

“The removal of the 10 per cent growth cap for investor loans in April 2018 has not driven higher growth in that category of lending,” he said.

“Interest-only loans are only about 17 per cent of new loans, which suggests that the 30 per cent limit is not the primary constraint — tighter lending standards and a greater focus on responsible lending are likely to continue to limit supply of credit.”

The Finder analysis showed Macquarie Bank was also among lenders that had cut interest rates on several of its investor mortgages in the past two months, including principal and interest and interest-only loans.

P&N Bank — Western Australia’s largest customer-owned bank — this week informed mortgage brokers of a host of interest rate reductions for fixed-rate owner-occupier and investor home loans.

The changes become effective tomorrow.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout