Almost history: Westpac’s long, hard road to prosperity

Westpac chief Brian Hartzer was working in New York in the 1990s when Australia’s oldest bank was in near meltdown.

Westpac chief executive Brian Hartzer was working in New York in the early 1990s when Australia’s oldest and second-largest bank was in near meltdown.

A vice-president with the First Manhattan Consulting Group, he was part of a team advising the troubled bank, which was reeling from its major exposure to the commercial property sector that had turned bad when Australia fell into a serious recession.

“I was consulting to Westpac in their New York office when things turned really ugly,” Mr Hartzer told The Weekend Australian in an interview reflecting on the bank’s 200-year anniversary, which it marks next week. “I remember being in a meeting in the Westpac office when one of the people there explained that there was this guy called Kerry Packer who had come on to the board and they were dramatically shutting down their international operations.”

Packer’s buy into Westpac, and his short-lived but tumultuous time on its board, were part of one of the worst experiences of Westpac’s history. The bank was struggling and if it had collapsed, the chances were that the severe recession at the time could have sent the Australian economy into a full-blown depression.

Sitting in his sunny office overlooking Sydney’s Barangaroo and the blue harbour, with a Sidney Nolan painting of Ned Kelly over his desk, Mr Hartzer can comfort himself that while life isn’t exactly easy in banking today, the lessons learned from that horrible time have helped shape the very profitable bank he heads today.

The crisis saw Westpac cut back its operations in the US and Asia, avoiding some of the problems that beset some of its competitors and their offshore operations, and adopt a much more conservative approach to property lending.

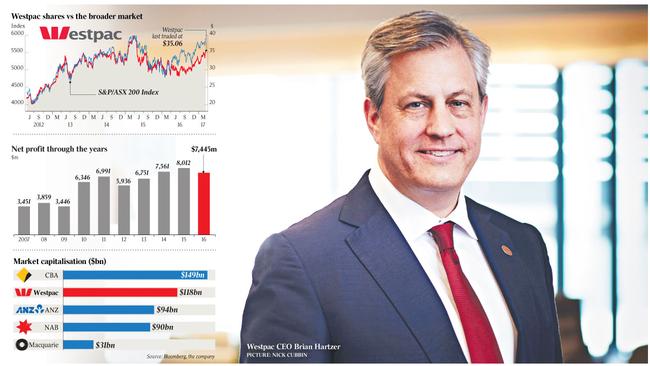

With a market capitalisation of more than $118 billion, Westpac turns over more than $22bn a year, had a last annual net profit of almost $8bn and has about 40,000 staff members.

“The experience is very live for all of us here,” says Mr Hartzer, who came to Australia in the 1990s, working for ANZ Bank. He has been running Westpac for the past two years.

“It is absolutely fundamental to the policies we have today. We absolutely have a view and an intent — never again.

“It’s not to say that nothing can go wrong but we are incredibly alert to risk. Every month we talk about our various types of risk exposure based on the experience of the early 90s.

“Bob Joss (the American brought in to run the bank at its low point) and (his successor) David Morgan, who lived through it and helped the recovery, instilled a very conservative credit policy which Gail Kelly continued and I have continued.”

Mr Hartzer says the crisis of the 90s meant Westpac “stuck to its knitting. Our notion is that we are a strong regional bank here in Australia and New Zealand, with the fundamental purpose of supporting the economies of Australia and New Zealand.”

Regal Funds Management analyst Omkar Joshi says: “Westpac tends to be more conservative than many of its peers and this conservatism has been shaped by its experience in the early 1990s. They are a well-managed bank which is well placed in a tough operating environment.”

The American-born Mr Hartzer is now the custodian of the first minutes and ledger book of the Bank of New South Wales, which date to November 1816 when a group of business people decided to found the colony’s first bank.

The bank opened its doors in Sydney’s Macquarie Street on April 8, 1817.

“The whole foundation of the bank was (governor) Lachlan Macquarie believing there was this opportunity for a private economy to grow at a time when Australia was essentially a state-owned enterprise,” says Mr Hartzer, who studied European history at Princeton and has become an enthusiastic student of Australian history. He argues that “the history of Westpac is the history of the Australian private economy”.

As he prepares for next week’s celebrations, which culminate in the Westpac Bicentennial Ball in Sydney on Saturday night, Mr Hartzer declares he likes to think “Westpac is the red thread running through the golden tapestry of Australia’s economy history”.

He points out that Westpac was the banker to the Australian Gas Light Company, which was the first company to put gas lights in Sydney and remains a customer today. “It’s a relationship which is 175 years old,” he says.

Early last century, the then Bank of New South Wales took the first deposit from a new company named Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services, based in Winton, Queensland. Mr Hartzer recently gave Qantas chief executive Alan Joyce a copy of the ledger from the Winton branch showing its early accounts.

“We have the relationship with Qantas to this day as well. We have these relationships which literally last for centuries,” he says.

“The value of the company is in direct proportion to its ability to build and sustain relationships which last over time. When you start with that premise, it colours your approach to business. It is not about individual transactions, or making money on a particular deal. It is about how can we help this customer over time.”

Looking back over the company’s history, Mr Hartzer also recounts that it was the Bank of New South Wales general manager in the 1930s, Alfred Davidson, who called for the devaluation of the Australian pound as a way to get the country out of its severe depression. “It was directly counter to the policies of the various economic officials at the time,” he says. “He was able to use the strength of the Bank of New South Wales and some of its international trading relationships to essentially force the devaluation of the Australian pound, which is one of the things that, a few years later, everybody acknowledged that pretty much saved the economy from the Depression.”

Mr Hartzer argues that Westpac has also been a leader in encouraging more women in its workforce, having been the first bank to appoint a woman teller, and a woman bank manager, with former chief executive Gail Kelly becoming the first woman to run a major Australian bank.

Mr Hartzer says Westpac’s strong culture has generated a continuing camaraderie between Westpac chief executives, with Ms Kelly and her predecessor David Morgan attending Mr Hartzer’s recent 50th birthday celebrations at the Sydney Opera House.

Mr Hartzer says he still believes it was a good idea for Westpac to move into the wealth management business, which it did with the acquisition of BT, despite some of the problems that wealth management divisions have caused for some banks.

But he admits “we have certainly learned a few lessons along the way. The starting point for us is that we want to help people through their financial lives.”

But looking back, he says, the moves by the Australian banks into wealth management came through buying businesses that had been based on the old model of insurance brokers selling product on a commission basis.

As he points out, banks run a different business model, which is not about making commissions from one-off sales of insurance products but about long-term relationships with their customers.

He says BT has responded to the need for change, moving to a fee-for-service approach and operating with an “open architecture approach” where its financial planners can sell products produced by a wide range of companies in addition to its own.

Mr Hartzer says he expects Westpac to still be in the wealth management business in the future “unless there is some sort of drastic intervention”.

“But it has to be done in a way where conflict of interest is well managed and customers’ interests are paramount.”

Westpac’s celebrations next week will be tempered by the fact that all Australian banks are operating in a highly charged political environment that could well see them face a royal commission if Labor is elected in two years’ time.

Mr Hartzer argues that banks are already well regulated in Australia and are addressing the recent problems raised.

He says a royal commission would only cost the taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars and “be a lawyers’ picnic”.

And he warns that continuing piling of regulations and controls on banks around the world “has consequences for the strength of the economy”.

He says Donald Trump’s promise to roll back the regulation of US banks has at least raised the discussion of “how much is enough and when it is going too far”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout