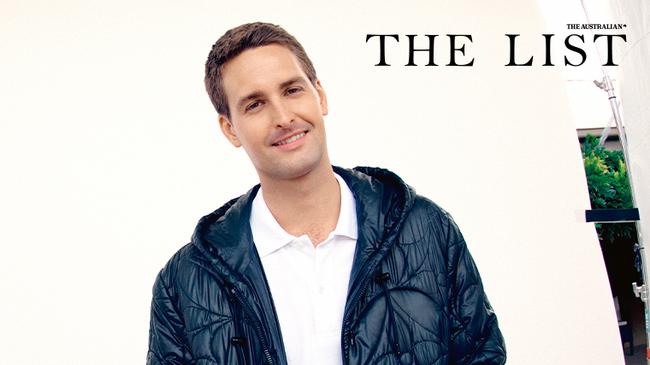

Evan Spiegel on changing the face of social media

Snapchat founder Evan Spiegel talks frankly about the app that changed global communication, the hunger he recognises in Australian startups, and what wife Miranda Kerr has taught him.

Get a glimpse into the future with The List: 100 Innovators 2022, a celebration of Australia’s boundary pushers and innovators. Find it in The Australian on Friday, July 15 in print and online.

On May 16 this year, Evan Spiegel stood before the graduating class of 285 students at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles to deliver a commencement address like no other. That the founder of one of the world’s most successful tech companies – Snap Inc. – was visiting the campus of this small non-profit university was reason enough for many of the students to get excited. But Spiegel and his wife, Australian supermodel turned clean-beauty entrepreneur Miranda Kerr, were not there simply to inspire the students: they had an announcement to make.

Spiegel had attended Otis College for summer design programs as a teenager, before moving on to Stanford University. And after a speech in which he spoke of the profound impact it had on his life and his outlook, the 32-year-old billionaire turned the podium over to the school’s president, Charles Hirschhorn.

With the couple seated behind him, Hirschhorn faced the graduating class and revealed that through their foundation, the Spiegel Family Fund, the pair had just made the largest gift in the college’s history. And the grant – reportedly worth north of $14 million – would allow the entire class to pay off their student loans. The room erupted in celebration.

“It is a privilege for our family to give back and support the Class of 2022,” said Spiegel and Kerr in a statement after the news broke, “and we hope this gift will empower graduates to pursue their passions, contribute to the world, and inspire humanity for years to come.”

The future has long been on Spiegel’s mind. Since he launched Snap in 2011, the social media platform has grown into a multibillion-dollar behemoth, defying the critics – and fierce competition from the likes of Instagram and TikTok – with millions of encrypted disappearing messages crisscrossing the planet every single day. But Snap’s decade-long journey of invention, experimentation and cat filters began humbly, almost accidentally, at founder Evan Spiegel’s father’s house, where a formative attitude of “dare to fail” prevailed.

“My parents always let me try no matter what I was interested in, no matter how ridiculous it was or how likely it was that I would succeed,” he says.

“In second grade I decided I wanted to learn how to play the trumpet, and my mum gave the OK straight away. So I rented my trumpet, I signed up for class, and within a couple of weeks it was pretty clear that I had no future as a trumpet player.

“It was pretty much a disaster, but my mum never made me feel bad about it.

“She just said ‘OK, we’ll return the trumpet, and maybe you’ll find something else you like’. And my parents were always just very open with letting me try stuff, and eventually that extended to computers.” Spiegel was raised in California with two younger sisters, attending the same school – Crossroads at Santa Monica – throughout. He says that despite the fact he was never allowed to watch TV while growing up, his parents did let him build his own computer, just as long as it wasn’t connected to the internet.

He’d spend hours tinkering with graphic design and code at the Crossroads computer lab, until his father eventually told him to go and get a job.

“One summer I interned working on a biomedical computation project for Abraxis BioScience, which essentially makes cancer drugs,” he says. “And so we were all discovering new drugs by running simulations on GPUs (graphics processing units).

“I just got to see and experience and try all sorts of different things and I failed at all of them, but along the way I somehow made it to school (Stanford University), where I met Bobby (Murphy, co-founder of Snap) and then we failed on a couple more things, before we had our success.”

The success the 32-year-old Spiegel refers to is Snapchat, now used by more 330 million people globally every single day, and 530 million every month, with its growth outranking that of giants Facebook and Twitter. It’s an app that has spawned numerous imitators and made billionaires out of its co-founders, and whose roots can be traced back to a class project in which, like something out of a scripted sitcom about starting a tech company, Spiegel and his wildly ambitious early co-founding team were completely unaware they were building something that would fundamentally change the way we communicate.

“A friend of mine was living down the hall from me at school, and we were hanging out one day and he was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’d love to send pictures that disappear’,” Spiegel recounts. “And I was like, ‘Oh, that’s really interesting’, so we started building a prototype. Bobby and I were working on another project at the time, but we started building a prototype, and we called it PiccaBoo.

“When I presented to the class, of course everyone is like, ‘Well, this obviously doesn’t work because you can just take a screenshot, so no one’s going to use it’. But Bobby and I really liked it, because we were just sending photos back and forth really quickly. Back then, it took about a minute to send a photo via MMS, but we invented a way to send them much faster.”

Snapchat’s functionality was much faster than texting – and far less expensive – and caught on quickly among Spiegel’s friendship group.“ We were talking with pictures, so we renamed it Snapchat,” he says. “By this time we were working on it at my dad’s house, and we launched it in the app store.”

The biggest early challenge Snap faced was raising money, Spiegel says, after some initial seed capital from his grandparents and from Murphy, who was working a second job. “My dad said ‘I’m not spending any more money on disappearing photos’. But the server bill at the time had got to about $10,000 per month, which was serious.

We were getting close to hitting a wall, and I remember I got a Facebook message from an investor. His name’s Jeremy and his profile picture was with Obama, so I thought, ‘That seems legit; he’s met Obama’,” he says. “I responded to his message, we met, and his partner’s kids really liked Snapchat. I remember it was Angry Birds, Instagram and Snapchat.”

Early data showed Snapchat “wasn’t a flash in the pan”, Spiegel says. Kids and teens were not only downloading the app but continuing to use it. “Those days were a lot of fun,” Spiegel says. “We raised a bit of money and that allowed us to hire two of our friends, Daniel (Smith) and David (Kravitz), and we were still in my dad’s house. We had seven people living in my dad’s house.

“We grew out of that house, and the focus became – and still is to this day – building stuff for the community, so things like the Android version of the app, adding drawings, and we invented the thing where you tap to take a photo and hold for video.

“The story of the growth of the business was really just about trying to innovate as quickly as possible to make new stuff for our community.”

Spiegel says one of the great things about the technology industry is that the data speaks for itself. Whenever he and his friends were trying to raise money or talk to investors, they would bring the graphs of data showing how people were using the product, and even if the investors didn’t necessarily understand the technology behind Snapchat – how it was using the camera in new ways or how ephemeral messaging works – they understood its users were on it all day and using it as the primary way to talk to their close friends.

“The other thing about the technology industry is how helpful everyone is,” Spiegel says. “It’s a hallmark of the industry; people were willing to give us advice and help us through our challenges. And that’s something I really like about the industry, how it rewards openness and rewards you when you say ‘I have no idea’.”

If there’s one person other than Spiegel who was critical to Snapchat’s birth and subsequent rise into social-media superstardom other, it’s co-founder Murphy. Spiegel smiles widely when speaking about his old friend and it’s clear the admiration is mutual.

“I love Bobby,” Spiegel says. “I feel so blessed to have the opportunity to work with him, and that’s why we are here today. Out first project was called Future Freshmen – it was an absolute disaster, but we just loved working together. It’s all we wanted to do, and basically 24/7, for as many hours as we could stay awake, we wanted to work together and it’s been a blast ever since.

“We see the world in different ways and we do challenge each other, but we’re also so aligned in what we’re trying to create in the world. I don’t know, I just feel like I won the lottery to get to know him and the friendship we have is just amazing.”

It was Murphy, Spiegel says, who was responsible for one of Snapchat’s smartest early moves – bringing in an outside engineering leader. Snapchat’s early engineering team was just eight people, but it quickly grew to 100, and soon 300.

“Bringing in a leader who had led a couple of hundred people before was critical. We were always trying to think ahead and bring in leaders who had that expertise and seen the scale we were trying to achieve,” Spiegel says.

“That has helped us time and time again, and we just feel really lucky because every day we go to work we learn from all the people we work with. This is the only business we’ve ever worked at and we still have a ton to learn, and the people we’ve assembled across the company teach us stuff all the time. “I feel like I’ve had to become a new person every six months just in terms of how much you have to learn and grow just to keep up with the growth of the business.”

Aside from Murphy, Spiegel cites Snap chairman Michael Lynton as a crucial mentor and a cool head who has helped steer the business at every step. The veteran entertainment industry executive and former Sony Pictures CEO is the husband of renowned journalist and TV producer Jamie Alter Lynton, and recently joined the board of publishing giant Condé Nast.

“I met him when we were working in my dad’s house. His wife sent an email to the support email, and I was answering the support emails at the time, and their kids had been using the service. And she liked our privacy policy because it actually made sense, so she sent us an email and was like, ‘You know, I’d love to meet up sometime’, and I said I’d love to, and she’s like, ‘How about tonight?’, and I said ‘Sure’. So I drove over to their house and had dinner with their family, and Michael, he’s an incredibly talented and thoughtful leader.

“So all the way my dad’s house, to today, and now he’s the chairman of our board and has been for a really long time, and there are plenty of stories like that where we’ve just had people who really gone out of their way to help us and mentor us.”

As for advice for entrepreneurs today, Spiegel cites two key lessons – the first from a Stanford class on entrepreneurship and venture capital that reminded students “You have two ears and one mouth, use them in that proportion”.

“That lesson has really stuck with me as a leader, especially in a business where we’re trying to make stuff that people want to use,” Spiegel says.

“The way to do that is by listening and listening really carefully, to our team members, to our community and to our partners.”

The second lesson comes from when the Snap team were still working at Spiegel’s father’s house, and it was delivered by Peter Fenton, general partner at venture capital outfit Benchmark.

“It was the early days of our business, and we’re just starting to get momentum and more interest in the business and he said, ‘Evan, you just got to get really good at saying no’,” Spiegel recounts. “I asked what he meant and he said, ‘As the business gets more momentum, people are wanting to want to do partnerships, and they’re gonna want you go and speak at their conference and spend time helping them with their business. Just say no and focus on serving the community’. And that for us was so crucially important, because when you’re a small company your resources are so limited.

“It’s so hard to invest in any new product or new feature, and so by really focusing, that helped us continue to grow the business at a fast pace and never lose sight of the important thing, which is serving our community.”

Australia is where Spiegel established Snap’s Asia Pacific headquarters, and the company has a fast-growing presence in its Sydney HQ.

He’s a regular visitor to Australia, especially given that he’s married to the Gunnedah-raised Kerr. The pair met at a party hosted by Louis Vuitton at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and now have two small children together, sons Hart, four, and Myles, two, as well as Kerr’s 11-year-old son Flynn from her first marriage to actor Orlando Bloom.

Their first date was at a Los Angeles yoga studio and Spiegel says Kerr recently introduced him to a new type of yoga – Kriya – that he says has changed his life.

“The energy and clarity I get from meditating has just become addictive for me,” he says. “That‘s something in the past couple of years that has been really useful, especially through stressful leadership challenges and managing the pandemic, and just everything that‘s been happening.”

Spiegel says he’s been incredibly impressed with the Australian startup founders he has met on his multiple jaunts Down Under.

“What our teams are doing in Australia is amazing,” he says.

“A lot of our work on real-time calling is work happening in Australia. “What’s also so exciting is the thriving Australian startup scene, and one of the things I’ve noticed is that so many brilliant founders seem to think global first, and that’s unique.

“Maybe it’s just the perspective from being in Australia, but the ambition to build a global business is so clear and you can feel it so strongly across Australian founders, and I think that’s why you’ve seen some of these just massive breakout global success stories from Australia. It’s really super exciting.”

This year is shaping up as a difficult one for the tech industry, with investors spooked by rising inflation and the ongoing war in Ukraine. The market jitters and supply chain issues have also hit Snap, whose share price was sent spiralling after Spiegel announced a hiring slowdown. It plunged by about 30 per cent after the CEO sent an all-staff email announcing the company will miss its own targets for revenue and adjusted earnings in the current quarter.

“Responsibly managing our expenses will allow us to invest through this period of time and emerge stronger as a business. Moving forward, we will be taking steps to reprioritise our investments, continuing to invest across our business priorities, but in many cases doing so at a slower pace than we had planned, given the operating environment,” he wrote to all Snap staff in May.

But Spiegel is a born optimist, and he remains ultimately very bullish about the next decade for his company. To date, Snap’s decade-long journey has been about becoming the place to capture memories and communicate with close friends. But according to Spiegel, its next 10 years will be about augmented reality and reinventing the way we use a smartphone’s camera and how we use it to communicate.

And while some company founders might be tempted to go and start their next project, Spiegel says he isn’t going anywhere.

“I really admire serial entrepreneurs,” he says. “But I don’t know how on earth they have the stamina to do it. I love Snap and I would love to stay at Snap as long as I’m useful. And I just feel so blessed – I wake up every day and work with our team and work on all these cool new products, and that’s what I’m focused on.”

Snap’s founder might be staying put. But with the Spiegel Family Fund committed to philanthropic projects across the arts, education, housing and human rights, Spiegel and Kerr are creating a legacy that reaches far beyond those who use the platform he created. Together, they are helping to foster the next generation of entrepreneurs, kids just like the Otis College students whose ideas will one day shape the way we live, work and communicate and whose future now looks a whole lot brighter – no filter required.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout