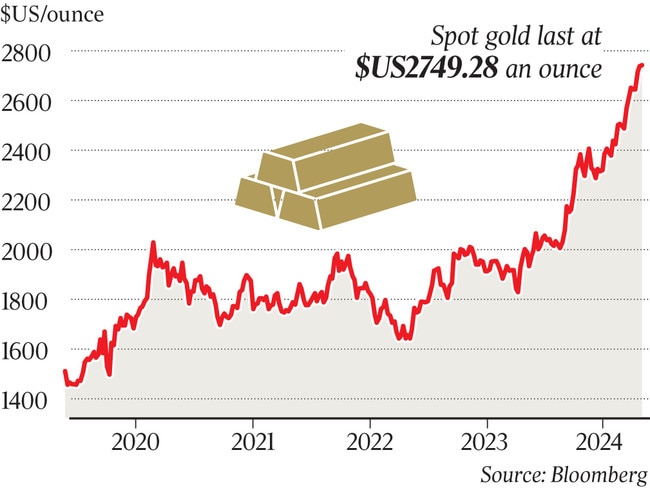

A 30 per cent year-to-date rise easily exceeds a 22 per cent rise in the S&P 500.

In recent months the rise accelerated despite some headwinds.

A 5.2 per cent rise in September has been followed by a 4.5 per cent rise in October even as the amount of US interest rate cuts expected in coming years receded on improved US economic data over the past two months.

Despite some easing of the Middle East conflict that pushed crude oil down about 6 per cent on Monday, gold soon recovered and was closing in on the record high of $US2,758.49 per ounce hit last week.

Gold has risen eight of 10 months this year, hitting 36 new record closing highs.

There are plenty of reasons to stay bullish for the longer term, according to World Gold Council senior market strategist John Reade.

But to the extent that gold has been boosted by hedging against the risk of US fiscal largesse and draconian trade policies stemming from a sweep of Congress, it may be hit by the selling of those hedges around the time of the election – assuming a close result.

“If you look at what happens when either party wins everything, a so-called sweep, deficits tend to be bigger because the President can get through his agenda,” Mr Reade told The Australian.

“I think what we’ve seen in October – when the dollar has been strong, US interest rates have been going up and gold has been going up – is people pricing in a more extreme result, and that more extreme result, based on the opinion polls and so on, is probably Trump wins everything.

“But if Harris wins everything, it’s not necessarily bad for gold either.

“There is some risk here – because of positioning, because of how gold has moved this year – that if you see one party or the other win, but not get control of Congress, you get some profit taking.

“I think the strength in gold this month is more a reflection of people being worried about a sweep and probably a Republican sweep, because if you do get a Republican sweep, you will probably have tariffs, you’ll probably have higher inflation, you’ll probably have lower growth and you’ll probably have more weaponisation of the US dollar and the financial system which would be good for gold.”

But while betting markets show Donald Trump has opened up a significant lead over Kamala Harris before next Tuesday’s election, opinion polls suggest a much closer result.

Even as the Federal Reserve jacked up interest rates in 2022 and 2023, gold began to take off in late 2022 as other central banks – particularly China – emerged as major buyers, driven by inflation concerns and geopolitical events like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

More recently, Western investment demand, much of it via ETFs, picked up as interest rates peaked.

“The biggest change that’s taken place in the gold market is we went through a phase for a couple of years of ignoring what was happening in terms of the US dollar and interest rates,” Mr Reade said.

“Normally, you expect gold to do poorly when the dollar is strong and when interest rates are rising, but gold didn’t correct to the extent or at all actually that people were expecting.”

The most obvious thing that changed was the fact that central banks, which have been net buyers of gold every year for since the global financial crisis, doubled the amount of gold they purchased in 2022 and become a more meaningful contributor to the demand side of the equation.

Apart from China, central banks in Singapore and emerging markets have been the main buyers.

Overall they doubled their gold buying from 2022 as inflation swung from being a problem of “not enough” to “too much”. Inflation has peaked but it may be a “more of a struggle to keep it down”.

“So you change your inflation outlook, you change your gold allocation,” Mr Reade said.

But a bigger motivator for central bank buying of gold has been a consequence of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the sanctioning of the Central Bank of Russia that took place afterwards.

“Emerging markets, who aren’t automatic allies of the West, have reconsidered what they should hold in their foreign exchange reserves, and owning gold – either in your own country or in a neutral location – is seen as a better thing to do since the Russian invasion of Ukraine than it was prior.”

Russia lost access to about $US300bn of its foreign exchange reserves which were frozen by Western countries after it invaded Ukraine. De-dollarisation could be another driver of central bank buying.

After looking at a major discrepancy between reported and unreported gold buying which emerged in mid-2022, Mr Reade has concluded that China was behind the bulk of the unreported purchases.

As for why a central bank might not want to say how much gold it’s buying, he said: “They might want to buy an awful lot more.” By disclosing some buying to a market which leaks information, the PBoC may hope that will satisfy the market’s interest without driving the price up.

“So the central bank story has been a big part of how gold has done well in a strong US dollar environment, in a high US interest rate environment,” Mr Reade said.

“I think the second thing that’s that seems to have taken place over the last couple of years is that emerging market buyers of all types – not just central banks, but retail investors, jewellery investors, high-net-worth individuals – all types of buying of gold from emerging market investors who have displaced the relative importance of Western buyers of investment and speculative gold.”

That’s been driven by idiosyncratic factors in China, Turkey and India.

The other big driver has been Western investment demand via ETFs. After persistent outflows for three years, ETFs finally started to see net inflows six months ago.

The most obvious reason for that has been the peak in central bank interest rates.

At the same time Asian high-net-worth individuals have been big buyers of gold.

“They don’t trade gold like retail investors or even institutional investors who are very much concerned about short-term performance; they think of generational wealth,” he said.

One of their main concerns is the long-term implications of rising indebtedness in the West.

“They typically like gold and at the moment, they don’t have as much gold as they want,” Mr Reade said.

“They missed the move in the beginning of the year, like a lot of other people did, and because they’re of their longer-term concerns, when gold dips, they come back into the market.”

But after looking at the trends in gold demand and considering how far it has come without a correction, he sees “nothing that really screams to me ‘2026 all-time highs in the price of gold’.”

The price of gold has been on a tear for the past two years, soaring 70 per cent in that time.