US Fed cuts rates to near zero to fight virus slowdown

The US Fed has slashed its benchmark interest rate in a bid to stop market turmoil from aggravating a likely coronavirus slowdown.

The US Federal Reserve has slashed its benchmark interest rate to near zero and said it would buy $US700 billion in Treasury and mortgage-backed securities in an urgent response to the new coronavirus pandemic.

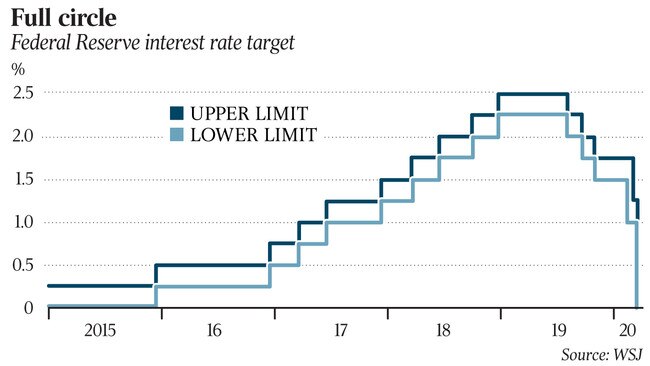

The Fed’s rate-setting committee, which delivered an unprecedented second emergency rate cut in as many weeks, said it would hold rates at the new, low level “until it is confident that the economy has weathered recent events and is on track” to achieve its goals of stable prices and strong employment.

“We have responded very strongly not just with interest rates but also with liquidity measures today,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said during a press conference, shortly before Asian markets opened.

The Fed will buy at least $US500 billion in Treasury securities and $US200 billion in mortgage-backed securities beginning Monday and continuing over the coming months to help unclog markets that grew dysfunctional last week, the central bank said.

The action followed an emergency half-point cut on March 3. Since the central bank began announcing its rate moves in 1994, the Fed has never moved to cut interest rates on two separate occasions in between scheduled meetings.

The coronavirus crisis has escalated sharply in recent days, with school closures and event cancellations cascading across the country. Companies sent workers home, and smaller businesses grappled with how to survive. Consumers, meanwhile, have stocked up for an uncertain period in which they are being asked to stay at home to combat the virus’s spread.

Many Wall Street forecasters now expect the economy will fall into recession during the first half of the year, and the shape of the recovery could be determined largely by how local, state and federal health officials mitigate the spread of the virus.

“The Fed is trying to prevent a health crisis from mutating into a financial crisis,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at accounting firm Grant Thornton.

Intense market volatility prompted the Fed to take several unusual steps last week to arrest strains in the Treasury market, considered to be the most liquid bond market in the world.

Those included offering nearly unlimited amounts of short-term lending to a group of 24 big banks, known as primary dealers, that function as the Fed’s exclusive counterparties when trading in financial markets. When banks were slow to take the Fed up on those loans, it pivoted Friday to buying $US37 billion in Treasurys in one swoop.

But late Friday it appeared those actions hadn’t restored normal functioning in the Treasury market -- let alone in riskier ones for mortgage bonds, commercial debt and municipal credit, prompting an even bolder approach on Sunday.

“Market function improved a little bit, but still, it wasn’t what we needed,” Mr. Powell said Sunday.

Treasury and mortgage-bond markets “are part of the foundation of the global financial system...If they are not functioning well, then that will spread to other markets,” said Mr Powell.

Mortgage rates, for example, spiked last week amid signs of dysfunction in the market for mortgage bonds that are government guaranteed, which could have hurt what has been a strong housing market. “They can’t allow that to happen,” Ms Swonk said.

Mr Powell said there were limits to the Fed’s ability to address lost income for households and small and midsize businesses. “We don’t have those tools,” he said. “We have the tools that we have, and we’ve used them.”

The response from fiscal policy makers in Congress and the White House, who can address those challenges more directly with changes in taxes and spending, would be “critical,” Mr. Powell said. “The thing that fiscal policy -- and, really, only fiscal policy -- can do is reach out to affected industries and affected workers.”

The central bank announced a series of steps to boost lending, including by lowering the rate charged to banks for short-term emergency loans from its discount window to 0.25 per cent from 1.75 per cent. That rate is lower than it was after the height of the 2008 financial crisis. It also extended to 90 days the terms of those loans.

The central bank said it would encourage banks to tap their capital and liquidity buffers to lend to households and businesses affected by the coronavirus.

It also adjusted a program with five other foreign central banks, including the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan, to make US dollars available overseas at near-zero interest rates and for periods of up to 84 days to ensure markets don’t run short of the currency outside of the US.

Many business transactions take place outside of the US. in dollars and foreign institutions also lend in dollars. The Fed used these “swap” lines aggressively in 2008 and 2009.

“The Fed did just about everything they could do, as a professional, operationally independent central bank with the tools they alone control, with great speed,” said Simon Potter, who served as the New York Fed’s markets chief from 2012 until last year and is now a fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

The rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee approved the actions with nine members in favour. One member, Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester, dissented against the decision to lower the fed-funds rate to its new range, instead preferring a range of 0.5 per cent to 0.75 per cent.

In a sign of the growing urgency behind these actions, Mr. Powell said the Fed had decided last Thursday to convene this weekend rather than wait for its regularly scheduled meeting this coming Tuesday and Wednesday, which now won’t happen. The central bank also opted not to release traditional economic projections because the economic outlook is changing so rapidly.

When the economy recovers will depend on the spread of the virus, and “that is just not something that is knowable,” Mr. Powell said. “Writing down a forecast in that circumstance didn’t seem to be useful.”

Rising market volatility reflects a constellation of challenges. They include business continuity plans by Wall Street banks that have led trading teams to work from multiple sites or remotely; postcrisis regulations that have made individual large banks more resilient but restricted their ability to quickly warehouse assets being sold by financial firms; and hedge funds caught up in bond trades that became extremely unprofitable when volatility soared, leading to more volatility as those trades unwind.

Market functioning matters especially to the broader US economy because, compared with other wealthy countries, a greater share of economic activity is financed through bond markets rather than through banks.

The upshot is that the Fed is being forced to update its 2008 crisis playbook much sooner than anyone expected one week ago to prevent these dislocations from leading to a much more serious recession.

The central bank has a number of off-the-shelf tools it also could deploy, though some would require invoking emergency authorities and receiving sign-off from the Treasury Department.

One example is a facility to finance short-term commercial debt. Such a facility, which the Fed used during the 2008 crisis but which now would require Treasury Department approval, would help companies that rely on the commercial-paper market to tap short-term cash for unanticipated funding pressures. Mr Powell didn’t rule out using such tools in the future on Sunday evening.

The virus shock has delivered a blow to this market by raising concerns that borrowers will be less creditworthy as they face falling revenues. Clogged commercial paper markets could lead firms to instead draw on bank lines of credit, which could raise funding needs for banks.

Dow Jones Newswires