And this fear of future inflation could be the thing that determines if the Reserve Bank has to go harder in hiking interest rates.

The RBA governor Philip Lowe has made explicit his intention to return inflation back to the target of 2 to 3 per cent. But he has offered homeowners and businesses some respite: He doesn’t want to sink the economy in the process. Wanting something and being forced to do something are two different things.

There is a lot that can go wrong in efforts to tame surging inflation and Lowe admits the path to victory is “a narrow one”. Even some corners of the money market are starting to place bets that inflation will start to ease mid-next year.

But if the RBA missteps in its calculations on future rate hikes, it will have to go even harder in hiking rates if it is to retain its market credibility.

Australians don’t know what is about to hit them with a series of interest rate hikes to come – this comes on the back of the 135 basis points made in the last three months.

Next month will either be a supersized 75 basis point hike for August or continuation of a series of 50 basis point hikes until, as economists at ANZ this week forecast, the cash rate will be at 3.35 per cent by the end of the year.

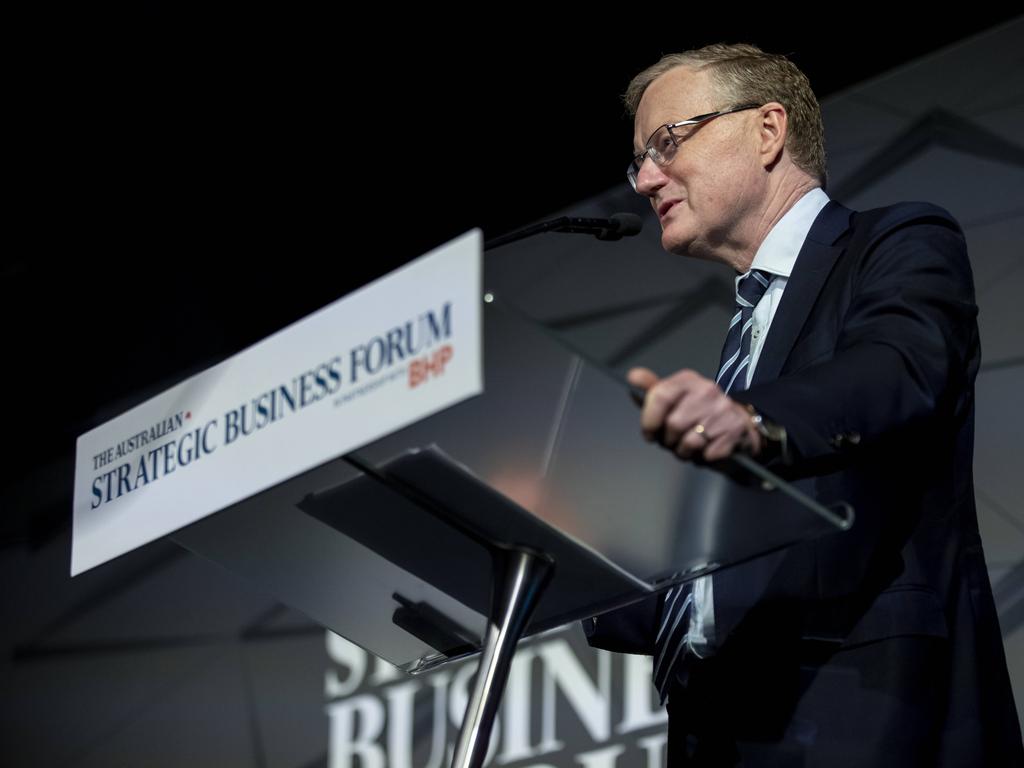

Speaking at The Australian’s Strategic Business Forum in Melbourne, Lowe has urged all Australians to steel themselves for the inflation battle.

Key to this is how we react to what are expected to be shocking figures this time next week that are set to show annual inflation running with a 6 or possibly even 7 per cent in front of it. This will take the consumer price index to near four-decade highs.

Lowe, who met with his central bank counterparts at a G20 finance meeting in Bali on the weekend, says the critical issue now facing central banks around the world is managing inflation expectations.

This inflation psychology comes down to households asking for higher wage rises than the economy can handle, or businesses simply putting up prices because of the expectations inflation will rise indefinitely.

If this happens then we will have trouble returning inflation to 2-3 per cent over any reasonable horizon, Lowe warns. That’s when the real pain comes.

RBA’s big review

One of the things that has seen Australia through every kind of modern economic cycle is the framework signed off by former Treasurer Peter Costello for the single focus of an inflation target for the Reserve Bank should be between 2 and 3 per cent.

Importantly, it has insulated us from the boom-bust cycle with a staggering three-decade run before Australia fell into a recession.

And through the Asian currency crisis, the commodities boom, September 11, the Global Financial Crisis to the Covid-19 shock, the inflation target has remained unchanged. For much of the past decade Australia has undershot the target and before Covid-19 hit the RBA set about on a path of loosening monetary policy, pushing the cash rate below 1 per cent.

Whether this band is fit for purpose will come under particular focus as Treasurer Jim Chalmers outlined the terms of reference for the RBA review.

The review will be spearheaded by former Bank of Canada deputy governor Carolyn Wilkins.

It is worth noting the Bank of Canada has a broader inflation target than Australia, aiming to keep inflation at the 2 per cent midpoint of an inflation-control target range of 1 to 3 per cent.

Chalmers says he has an “open mind” to the inflation targeting regime changing, although he has yet to have a proposal put in front of him that is better than the one we have.

Chalmers told The Australian’s Strategic Business Forum there have been “enormous changes” in the domestic economy since the current regime was put in place “but no broad-ranging opportunity to pause and think about where the setting of monetary policy fits into this evolving landscape”.

Just because the inflation targeting has worked for three decades, doesn’t mean it should escape scrutiny. A review should also seek to look through the painful breakout of inflation Australia is currently experiencing as part of a global squeeze.

It should also formally answer the question of wages growth and whether that should be part of the RBA’s mandate. Under Lowe wages have played a bigger part in the central bank’s thinking around financial stability. Prior to the inflation surge the central bank governor had been actively urging businesses to deliver wages growth as a path to reinflate the economy.

Super returns

One person who needs to think broadly about inflation is the new chief executive of the $260bn Australian Super, Paul Schroder.

With investments in long-dated infrastructure as well as the demands on superannuation payouts, small changes in outlook for either inflation or the settings for interest rates can have a significant impact on the long term returns of his portfolio.

Speaking at The Australian’s Strategic Forum, Schroder said the review of the RBA is right but the central bank can’t be considered in isolation from fiscal policy, which also plays a significant role in driving demand through the economy.

Schroder says it’s logical to consider the inflation target and whether it’s suitable for the economy Australia is running.

Schroder, who took charge of the nation’s biggest super fund after long term boss Ian Silk retired late last year, says he understands the RBA’s position that the current range is an accepted position around the world and there would have to be a good argument to change.

“But it’s well worth thinking about, especially when we’ve had negative, real rates,” Schroder says and he points out that a slightly broader band “gives you a bit more scope” when it comes to setting monetary policy.

Schroder says his fund spends a great deal of thinking about the long-term direction of real interest rates and inflation. For him the megatrends all point to a low inflation environment over time. This is where it was heading before Covid and technology is set to play a big part of that.

“Really we should be thinking about a much longer-term horizon.

“That’s our business. Of course, we’re thinking about people’s retirement balances, but the way we’re trying to think about it is what’s happening right now is pretty bleak.

“It’s pretty uncomfortable the next 18 months or so. It’s uncertain, depending on largely how policy makers respond.

“But beyond that, there’s a fair degree of reason for optimism.

“I think there’s so many people who have forgotten that before Covid most of the world was worried that we were into this really deflationary cycle.

“There’s some really important megatrends that we should be thinking about, and most of them are deflationary.”

The biggest thing Australians now have to fear about inflation – is the fear of inflation.