RBA highlights zoning restrictions as key to more affordable housing

Urban planning and density restrictions are adding almost $500,000 to the price of an average Sydney house, the RBA says.

Urban planning and density restrictions are adding almost $500,000 to the price of an average Sydney house and locking in an “increasingly obsolete urban structure”, according to Reserve Bank research that suggests better zoning in Australia’s four largest cities would help make homes cheaper.

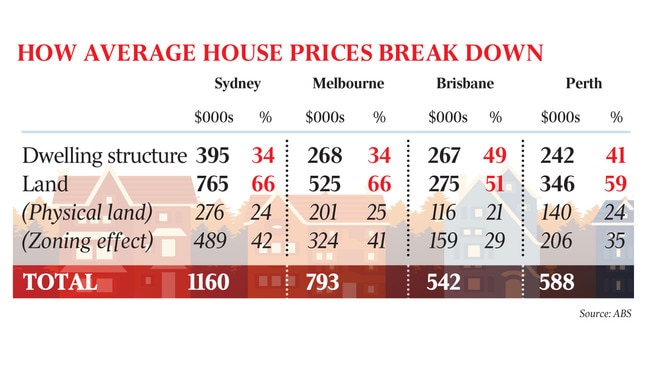

Between 29 per cent (Brisbane) and 42 per cent (Sydney) of the price paid for average houses in each the four biggest state capitals arose from an array of state and local government zoning rules that artificially limit building height and land use.

The effect has been rising over time in all four cities since the early 2000s. “The reason land is expensive is not because it’s physically scarce,” the authors said, revealing that the inherent value of land was about $400 a square metre or $277,000 for the average Sydney block, rather than the $765,000 implied by actual sales data in 2016.

“The difference represents what homeowners need to pay for the right to have a dwelling at that location, or the cost of ‘administrative scarcity’,” it said.

For example, when a 363ha site in Wyndam Vale about 40km west of Melbourne was recently rezoned from rural to residential, its value jumped from $120 million to $400m, the RBA said.

“Development restrictions have contributed materially to the significant rise in housing prices in Australia’s largest cities since the late 1990s, pushing prices substantially above the supply costs of their physical inputs,” the study said.

Apartments in Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney were between $110,000 and $399,000 more expensive because of the zoning effect. The impact of zoning was much higher closer to CBDs or coastal areas, where zoning in Sydney and Melbourne was adding between $700,000 and $1.5m to house prices.

The Australian recently reported over the year to November, 44 new homes were built in Woollahra compared with more than 4000 in Parramatta, suggesting zoning can have a large effect on price and supply dynamics.

“Even if zoning restrictions were relaxed, housing in Australia would remain expensive relative to cities where zoning is permissive and land is less physically scarce,” the study said, citing a separate study that found the “physical value” of land made up 4 to 9 per cent of house prices in major New Zealand cities.

This lower share compared with the four Australian cities could be because of the “constraints facing the expansion in Australian cities (eg. coasts and national parks) combined with high demand reflecting population growth and low real interest rates”.

Making zoning restrictions “less binding directly (eg. increasing building height limits) or indirectly, via reducing underlying demand for land in areas where restrictions are binding (eg. improving transport infrastructure) could reduce this upward pressure on housing prices”.

The study, written by economists Ross Kendell and Peter Tulip, said zoning also increased inequality. “As zoning regulations become more binding and contribute to increases in property prices, they represent a wealth transfer from future home buyers to current homeowners (and) result in higher rents,” it said.

John Daley, chief executive of the Grattan Institute, said the latest RBA study confirmed zoning was a “big part of the solution” to improving housing affordability.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout