But with COVID-19 continuing to cut off flows of Chinese tourists and students, and the political relationship continuing to hit new lows, how long will it be before there is permanent damage to the trade ties with the one country that, more than any other, underwrote Australia’s 29 years of uninterrupted economic growth?

Has Australia’s great trading relationship with China already passed its high-water mark?

At the moment, Chinese tourists and students who want to come to Australia have been blocked by COVID-19 travel restrictions, making it hard to judge whether their plans would have eventually been cut back as a result of political tensions between Beijing and Canberra.

But just when it seems the political relationship couldn’t get much worse, the federal government has this week warned that Australians travelling to China could face “arbitrary detention” and those in China who were thinking of leaving should get out as fast as they can.

It’s one thing to have the odd tit-for-tat political argument between trading countries, but quite another to expect trade with China to continue to thrive in the face of Canberra’s warning of its citizens that it is too dangerous to travel there.

The DFAT travel warning came after the arrest in Beijing this week of Xu Zhangrun, a prominent critic of Xi Jinping with close ties with Australia, and the imposition of tough new security laws in Hong Kong.

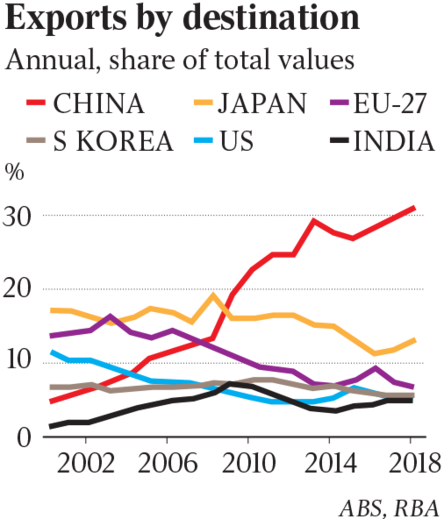

China has rejected suggestions that it is not safe for Australians to travel there, but the question remains: how long can strong trade ties continue with China with the government warnings against the people-to-people contact needed to drive it? As the Reserve Bank’s latest chart pack figures confirm, Australia’s exports to China have soared since the global financial crisis of 2008, while trade with other major buyers — Japan, India, South Korea, the EU and the US — has slowed or shown relatively weak growth.

Australia’s big increase in exports to China — now making up more than 30 per cent of total exports — has underwritten the Australian story, until February this year at least, of almost 30 years of economic growth, particularly over the past decade.

Australia’s trade with China is worth more than twice the trade with our next largest trading partner, Japan. China is the largest single foreign buyer of Australian services such as tourism and education, as well as wine, beef and wool.

Until recently, Australia-China watchers have been able to argue that while Beijing and Canberra may have their differences, Australia-China trade has continued strongly, with exports in many categories, including iron ore, wine, beef, tourism, education and dairy foods, at record or near record levels.

“China and Australia are mutually dependent,” Hans Hendrischke, professor of Chinese Business and Management the University of Sydney, said recently. “China needs iron ore and food from Australia for recovery and rebuilding. Australia, on the other hand, needs exports.”

The picture of a continued strong Australia-China trading relationship has been given a slightly artificially rosy glow due to the strong price of iron ore, driven by China’s continued strong level of steel production and Brazil’s misfortunes.

At what point does the cumulative pressure of COVID-19, people-to-people travel bans and the increasing political tension tip the scales in a permanent sense on the trade relationship?

While China can diversify its imports of beef, wine, coal, LNG and other foods, its students can choose to study in other countries and its tourists can choose to go to other destinations, the conventional wisdom has been that it cannot avoid buying Australian iron ore for the simple reason it that it needs it.

Or so the argument goes.

But as a new Lowy Institute paper argues, China is also looking to reduce its dependence on Australian iron ore by increasing its production of domestic iron ore and investing in potential iron ore mines in Africa.

A year ago there was a lot of attention given to delays in processing Australian coal at Chinese ports.

In May this year, tariffs of 80 per cent were imposed on some exports of Australian barley to China, and a ban placed on four major processing plants in Australia processing meat for export to China. Since then, the relationship has got worse.

Writing in the South China Morning Post on Tuesday, Kyri Theos, general manager of the Australian Chamber of Commerce in West China, presented the view of an Australian doing business in China in July 2020.

“Recent reports of cyberattacks and political interference in Australia have exacerbated anti-China sentiment, feelings that were already soured by COVID-19, barley tariffs and the politics of Hong Kong,” he wrote. “In China, public opinion towards Australia has turned negative.

“Australia’s call for an investigation into the origins of COVID-19 was poorly received. It reinforced the widely held view of Australia as a US lackey that has benefited from China’s growth.

“China’s economy is reopening and there are serious challenges for those of us seeking to reignite China-Australia trade.”

Australia is not the only country that is having political problems with China. The US is a prime example, with President Donald Trump and his administration choosing to challenge China on many fronts including launching a brutal trade war.

But Australia benefits from its trade with China, with a clear trade surplus, while the US has a trade deficit with China.

At the same time, China has been studiously cultivating a network of other countries through its Belt and Road Initiative, including Russia, Pakistan and the countries of Eurasia, developing its overland connections — and its trade potential — westward.

As Australia looks across the Pacific to the US for its political and military ties and cultural links, China is looking westward seeing Eurasia as a new land link to Europe and Russia.

Australia’s trade with its largest trading partner, China, had been powering ahead at near record levels of about $200bn a year going into the COVID-19 crisis, despite a deterioration in political ties between Australia and China.