How the economy was pulled back from the brink

The pandemic was fundamentally a health crisis, but for financial regulators it was impossible to predict the impact on the economy.

When the Reserve Bank board convened for a special monetary policy meeting a year ago, the sense of foreboding across the country about the course of the coronavirus was almost overwhelming.

The pandemic was fundamentally a health crisis, but it was impossible to even get a handle on the economic toll, as global equities slumped by one-third, liquidity evaporated, and the bond market effectively shut down except for the highest-quality issuers.

The RBA board met for the first time by videoconference, with governor Philip Lowe and deputy governor Guy Debelle among the four directors to attend the central bank’s Martin Place offices in person.

Five of their interstate colleagues were beamed in.

Lowe would later comment that the technology worked “remarkably well”.

So, too, did the package of measures announced by the governor at a sparsely attended press conference the following day, on March 19, which reflected the new environment of COVID restrictions.

A year later, ANZ Bank chief executive Shayne Elliott is tipping that gross domestic product might already have surpassed its pre-COVID level in late 2019.

Not only that, but the discussion between some economists had switched from the likelihood of a depression to the prospect of a boom - a word which Elliott confessed he had not heard “in a long time”.

“Back in March last year, we knew how a financial crisis progressed but there wasn’t too much experience to draw on for a global pandemic when large parts of the economy are consciously shut down,” a policymaker says.

“And then we had the added kicker of the health situation, where people were potentially going to die, and they did, although thankfully not too many.

“So the big unknowns were how bad would it get, and how were people going to respond - would they go completely into their shells, or would they go out and clean everything off the shelves of supermarkets and camping stores?”

Unusually, the outcome of the March 18 meeting was not announced until the following day, enabling the RBA to co-ordinate its emergency measures with the federal Government, the prudential regulator APRA, and the commonwealth’s debt issuer, the Australian Office of Financial Management.

While the tone of Lowe’s press conference the following day was sombre, the governor allowed himself a fleeting moment of exceedingly cautious optimism.

“As our country manages this difficult situation, it is important that we do not lose sight of the fact that we will come through this,” he said.

“At some point, the virus will be contained and our economy and our financial markets will recover.

“Undeniably, what we are facing today is a very serious situation, but it is something that is temporary. As we deal with it as best we can, we also need to look to the other side when things will recover.

“When we do get to that other side, all those fundamentals that have made Australia such a successful and prosperous country will still be there. We need to remember that.”

A year later, as the strength of the economic recovery confounds the most optimistic of pundits, it’s difficult to fault Lowe’s call, even with the benefit of hindsight.

There is little doubt that the nation’s financial regulators were instrumental in creating the right policy settings to help avert an economic collapse.

As former federal Treasury secretary Ken Henry told The Weekend Australian in January, the nation has handled the pandemic “pretty much better than anywhere else in the world”.

“That’s because history tells us that Australian governments listen to the experts in times of economic crisis,” Henry said.

“Globally, it’s been the biggest failing, so the government should be commended — if it hadn’t done so, we’d be in a much worse position.”

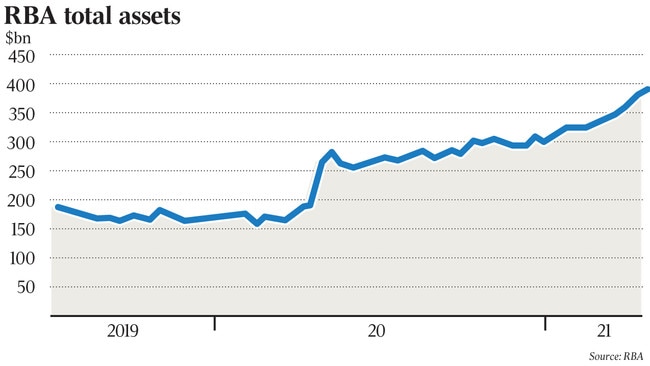

The emergency, $105bn package unveiled by Lowe was a mix of traditional and funky measures, including the RBA’s first use of unconventional monetary policy to buy bonds and encourage lending and investment by expanding the supply of money.

The bond-buying would ensure that the benchmark three-year bond yield, which is used to price corporate and government borrowing, would hover around 0.25 per cent.

This would approximate the cash rate, which was slashed by 25 basis points to a record low of 0.25 per cent.

The RBA also announced a $90bn line of credit for the banks, with incentives to pass on cheap rates to small and medium-sized businesses.

A further $15bn lump was handed to the Australian Office of Financial Management to invest in wholesale funding markets used by smaller banks and non-bank lenders.

It wasn’t just the RBA answering the call to arms.

APRA and the Australian Securities & Investments Commission also enlisted to help entities work through any regulatory issues associated with the package.

Both said they would take into account the circumstances in which regulated institutions were operating, providing relief or waivers from regulatory requirements.

This included requirements for secondary capital raisings, audits and annual meetings.

ASIC would also work with financial institutions to accelerate the payment of outstanding remediation to customers.

With the cash rate close to zero, Lowe said the RBA had “done as much as we can there”.

The focus had therefore shifted to other measures to support low funding costs.

“That’s one reason we are trying to lower the government bond curve because that provides the benchmark interest rate for a couple of other interest rates,” the governor said.

“So we lower that and we are providing the banks cheap funding directly from our balance sheet.

“The focus is really very much on doing other things to get funding costs down and to promote the supply of credit.”

The world - and the virus in particular - seemed to be closing in on Australia, but Lowe rejected any suggestion it was a made-in-Australia crisis.

Investors, he said, were not testing Australia, or questioning the country’s economic fundamentals.

“What’s happening, and we saw this again today, is there’s widespread liquidation of financial positions around the world,” the governor said.

“We have a lot of people trying to close out positions and moving to cash; investors are very nervous about the future.

“They are unsure about how the health situation will develop, how quickly will we get on top of it, how is the medical system in many countries going to cope, and in countries which have lockdowns, how long are they going to last?

“Until we can answer those questions, we are going to live with a lot of uncertainty and a lot of volatility.”

Last May, even the most optimistic RBA economic scenario was depressingly bad.

If the virus were contained in the near term and containment measures were phased out over the following months, much of the decline in GDP could be reversed over 2020-21 as consumption and employment growth rebounded.

However, the unemployment rate would still spike to 10 per cent before returning to pre-COVID levels by mid-2022.

The baseline scenario was that GDP growth would start to recover in the second half of 2020, although very large contractions in the March and June quarters would result in a year-end decline.

Unemployment would fall significantly from its June 2020 peak of about 10 per cent but would still be above its pre-COVID level in two years’ time.

As it’s turned out, the economy has consistently outperformed the most optimistic scenario, despite condemnation of the RBA’s baseline script as rose-coloured.

The single most important remedial measure, according to the policymaker, was the health response, which positioned Australia for a whiplash economic recovery compared to other advanced economies like Germany, France, Italy and the UK.

After that, it was the fiscal response - by late last year a $257bn torrent of stimulus had been showered on the economy, equal to 13 per cent of GDP compared to only 6 per cent in the global financial crisis.

Added to that, there were about $260bn in home and business loans on deferral at the May peak, and various RBA programs to ensure liquidity was adequate, bank funding costs remained low and markets overall were stable.

For the policymaker, though, the issue is what happens from here.

“In a sense, the easy part is behind us and the hard grind is ahead,” he says.

“It’s great we’ve got the level of GDP back to where it was but it’s really not where we’d like to be, because we’ve got the same issues we had at the beginning of 2020.

“Growth is going to be much slower from here, and we still don’t know how the virus is going to play out - I’d be very careful about declaring premature victory over that one.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout