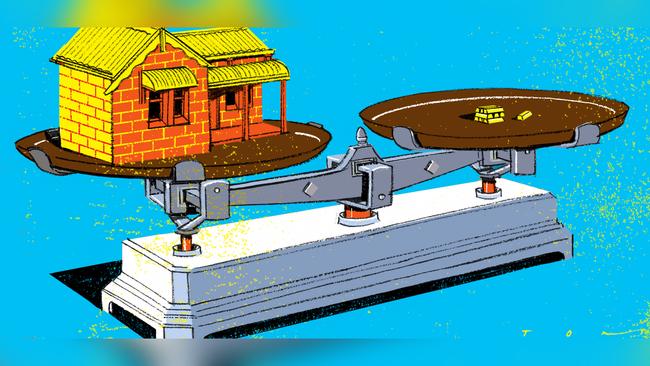

House prices up, but we’re as good as gold

We’ve created a lot of new money since the GFC; most of it went into real estate.

But when priced in terms of gold — for hundreds of years the international measure of value — it’s another story. The median Sydney dwelling price is $818,000. That’s 378 ounces of gold, about 10kg. A decade ago Sydney’s median dwelling price was $470,000, according to Corelogic data. That’s 373 ounces of gold based on the price back then. So the price of a Sydney houses has appreciated 75 per cent, but only 1.3 per cent in terms of gold.

It’s a worry; perhaps wealth hasn’t increased much and our wages, in term of gold, have plummeted. But don’t panic. Gold lost its formal role as the anchor of the global financial system in 1971. It’s no longer money but instead a speculative metal whose price tracks sentiment about the outlook for economic growth — and confidence in our money system.

Nevertheless, its rise in price should give central banks cause for thought. It’s naive to think the relentless march of so-called unconventional monetary policy isn’t eroding public confidence in the financial system. Central bankers have been fretting about the prospect of deflation, but might the gold price spike suggest the opposite?

The price of consumer goods has stagnated, but asset prices have soared. Had house prices, for instance, been included in the consumer price index, inflation would have been consistently above the Reserve Bank’s 2 per cent to 3 per cent target.

Surveys show people believe inflation to be closer to 4 per cent, whatever the official figures say. And for all the discussion among economists about how to finetune the inflation target, most of us have no idea what that is. Maintaining public confidence in money might be a better target.

If the Reserve Bank begins creating electronic money to buy government bonds in the new year, as many economists expect and as central banks have been doing abroad, the public might start wondering how much intrinsic value their deposits have.

Mark Creasy, a successful gold prospector in Perth, says the best long-term hedges against inflation are good real estate, agricultural land and gold. “Gold is a bit like fire insurance — the chance your house burns down is pretty low but you never know what is going to happen,” he said.

If the central bank can create money to buy government bonds from banks, why not give it to households directly, some might ask.

Why should bankers clip the ticket on the billions in new money and not ordinary people?

So-called quantitative easing may work in theory but economies are unpredictable and dynamic. Economic models don’t factor in public esteem for the monetary system.

Aside from the soaring gold price, potential competitors to government-sanctioned money have started springing up — Bitcoin, Ethereum, Libra — too. “Just because you’re a central banker doesn’t mean you have any more brains than average, you’re not a genius,” says Creasy, worth $826m last year according to The West Australian. “These people are playing around with things they don’t fully understand. Will QE work? I don’t know, but I’d have to say 45 to 55 per cent it won’t,” he adds.

Some central banks have become anxious. Russia and China have quietly quadrupled and tripled, respectively, their gold reserves across the past 10 years, to 2200 tonnes and 1900 tonnes, respectively.

The Reserve Bank sold its gold reserves, about 167 tonnes, for $2.4bn, or more than $400 an ounce, in 1997. The gold price yesterday was $2150 an ounce.

It’s not only central bankers who might be clouding the outlook for fiat currencies.

Private bankers have been furiously creating money and debt. Private banks, not the government or the Reserve Bank, create money when they grant loans and have a private incentive to create as much debt as people will take. For instance, the Commonwealth Bank’s balance sheet, about $975bn, dwarfs the Reserve Bank’s, which is about $170bn.

Since the financial crisis, the amount of money sloshing around the Australian economy — almost all of it created by private banks — has ballooned from $1.18 trillion to $2.14 trillion.

The bulk of this new money has been used to purchase existing houses and apartments rather than on ventures that would improve the capacity of the economy, causing enormous asset price inflation.

The extent to which the major banks pass on official cuts in the cash rate is irrelevant to their credit creation role.

Globally, private sector debt has increased from the equivalent of 100 per cent of gross domestic product in 2008 to more than 125 per cent.

At some point, relying on debt creation of private banks to maintain growth becomes unsustainable. How economies extricate themselves from this could be painful, requiring some sort of mass debt forgiveness, officially or not.

“This was recognised by the people in Babylon thousands of years ago, it was recognised by president (Franklin) Roosevelt when he revalued gold overnight in the 1930s, and it was recognised in the 1970s with the inflationary reset,” Creasy says.

We all know houses are much more expensive than they used to be, with more suburbs passing the $1m median price mark. That can be good for us, or bad — it depends from where you are viewing it.