Global economies are hanging on but can they for long?

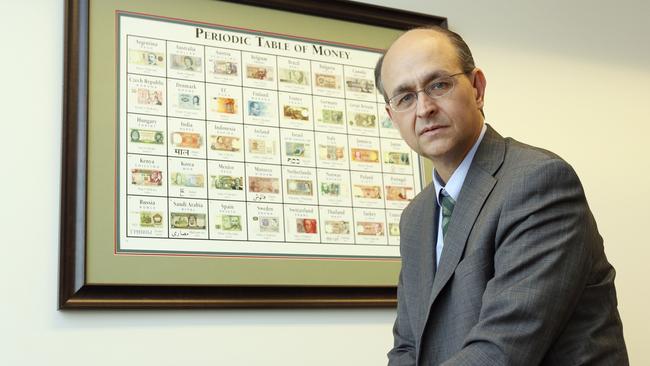

The desynchronised yet resilient global economy in the face of interest rate increases, energy shortages and China’s slowdown were the hot topics at Citi’s latest investment conference.

The desynchronised yet surprisingly resilient growth of the global economy in the face of rapid interest rate rises, energy shortages and China’s slowdown emerged as a key theme of Citi’ s Australia/NZ Investment Conference in Sydney last week.

Citi global chief economist Nathan Sheets said US resilience was due the fact that US consumers have been less sensitive to higher interest rates after paying down debt during an extended period of low interest rates, there had been pent-up demand for services after the Covid-19 pandemic, and the US had become more services intensive than many other economies.

Also, despite a meaningful tightening of lending standards by banks and less willingness on their part to extend credit to business after the lift in interest rates, credit spreads haven’t tightened much as the US now has a “rich ecosystem of lenders” apart from the banks.

There’s also a debate about whether the US is actually more resilient to rate rises or whether the lags in the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy are longer than history would suggest.

Mr Sheets feels it’s a combination of both, but notes that US private equity investors see more pain ahead for commercial real estate as the sector continues to adjust to higher interest rates.

“It may also be that there’s still more of a back-loaded adjustment to come, and I think that does behove us as investors in the Federal Reserve and other US policymakers to be careful,” he said.

Moreover, he expects a US recession to begin in the first half of 2024.

He points to five episodes in history where US wage growth cooled after growing as rapidly as it has done in the past six years.

In all five episodes, as part of the cooling in wage growth and inflation, there was a “meaningful rise” in the unemployment rate and recession.

He says a clear lesson from history is that if you want to “dis-inflate” the economy, if central banks need to lower wage growth and inflation, then it’s likely to entail a recession.

While there’s been a significant fall in inflation over the past 18 months, the core personal consumption expenditures price index (the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation) is well above the Fed’s target of 2 per cent, after falling from about 5.5 per cent to about 4 per cent.

“Our stance is that the easy part of the disinflation process has already occurred, and now it’s likely to be tougher sledding to get back to 2 per cent,” Mr Sheets said.

He notes that there’s been significant disinflation in commodities, fuel and food in the past 18 months, but recent developments in the Middle East bear watching. And with supply chains normalising and demand shifting back to services, there’s also been a significant softening of goods inflation.

But inflation on services, excluding shelter, hasn’t fallen much over the past two years.

“That’s really the domestic part of inflation that’s tied to the labour market,” Mr Sheets said.

“It’s roughly 50 per cent of the core PCE index, and the Fed’s going to look for meaningful improvement.”

His sense is that that’s likely to require a loosening of the US labour market and a recession.

While economists are currently split between those calling for a recession and those predicting a “soft landing” in the US economy, the main argument for a soft landing is “an empirical one”.

“It’s simply that through this cycle, we’ve seen many surprises from the economy, that the recovery and the rebound post-pandemic has simply been unique and different relative to what we’ve seen before,” Mr Sheets said.

“We don’t fully understand the process, but the data that have rolled in over the last year or so – gradual decline in inflation, some progress toward bringing down wages, gradual moderation in job gains – all while growth has been relatively solid, is consistent with the (soft landing) story.

“So I think the soft-landing school is more just an extrapolation of the data.”

In other words, economists may be suffering from a “recency bias” on the US economic outlook.

Citi expects the Fed to wait for a clear softening in the labour market before lowering rates.

After a much stronger-than-expected September non-farm payrolls report this may be some way off.

Europe also fared better than expected, with the natural gas shortage and rate increases causing stagnation rather than a severe contraction in growth, but stagnation is set to continue.

For the industrial north, it’s a “tough time to be a global manufacturer” as demand for manufactured goods is “pretty soft” as the skew continues to be toward services spending.

Germany, with its critical role in the euro area, has been heavily hit as a result of that weakness, particularly as it’s a major exporter to China, where economic growth has continued to disappoint.

There’s also been ongoing uncertainties and challenges associated with the energy transition in Germany and the industrial north, and meanwhile the ECB has lifted rates by 400 basis points.

Citi was hoping the services and tourism-intensive southern European countries would fare somewhat better than the north, but purchasing managers indexes tell a different story.

“Our sense is that this kind of cocktail of issues … the weakness of the north moving into the south, coupled with the monetary policy tightening, is likely sufficient that we’ll see a recession in the euro area through the second half of this year, and into 2024,” Mr Sheets said.

Europe is in a “very different place” to the US, due to the Ukraine war, and differences in energy dependency, goods versus services intensity, and willingness to draw down excess savings that were accumulated during the pandemic.

“The difference is not about the labour market, it’s not about inflation, but still the consumer is behaving very differently in the United States,” Mr Sheets said.

As for China, Citi now expects growth of about 5 per cent rather than the 6 per cent it was expecting this year.

But the world’s number two economy will still be a “reasonable driver” of global growth.

Mr Sheets expects some degree of stimulus in China will continue in 2024, limiting a slowdown in annual growth to 4.5 per cent to 4.75 per cent, which won’t be “really pivotal to our global outlook”.

More importantly, he expects China’s annual growth rate to slow to about 3 per cent over the next five years due to “the laws of economic gravity” rather than a “failure of the Chinese growth model”.

Said another way, as countries increase their per capita GDP, the reality is they tend to grow less.

Twenty years ago, it was easy for China to grow rapidly as people moved from the countryside into the cities, with significant gains to be had from urbanisation and industrialisation.

But much of that has played out, decisions that need to be made about the allocation of capital and other resources are much more subtle, and the opportunities for rapid growth more limited. China’s authorities have to accept the reality that growth needs to slow.

“There’s a risk that if they don’t accept those realities, and they overstimulate, then we’ll end up with more data and leverage and resource imbalances in the economy,” Mr Sheets said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout